In the recently concluded Global Gateway Forum 2023, the European Union (EU), in collaboration with the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) unveiled 11 trade corridors that the EU wishes to build in its bid to enhance regional integration in the continent as well as bolster EU-Africa economic cooperation.

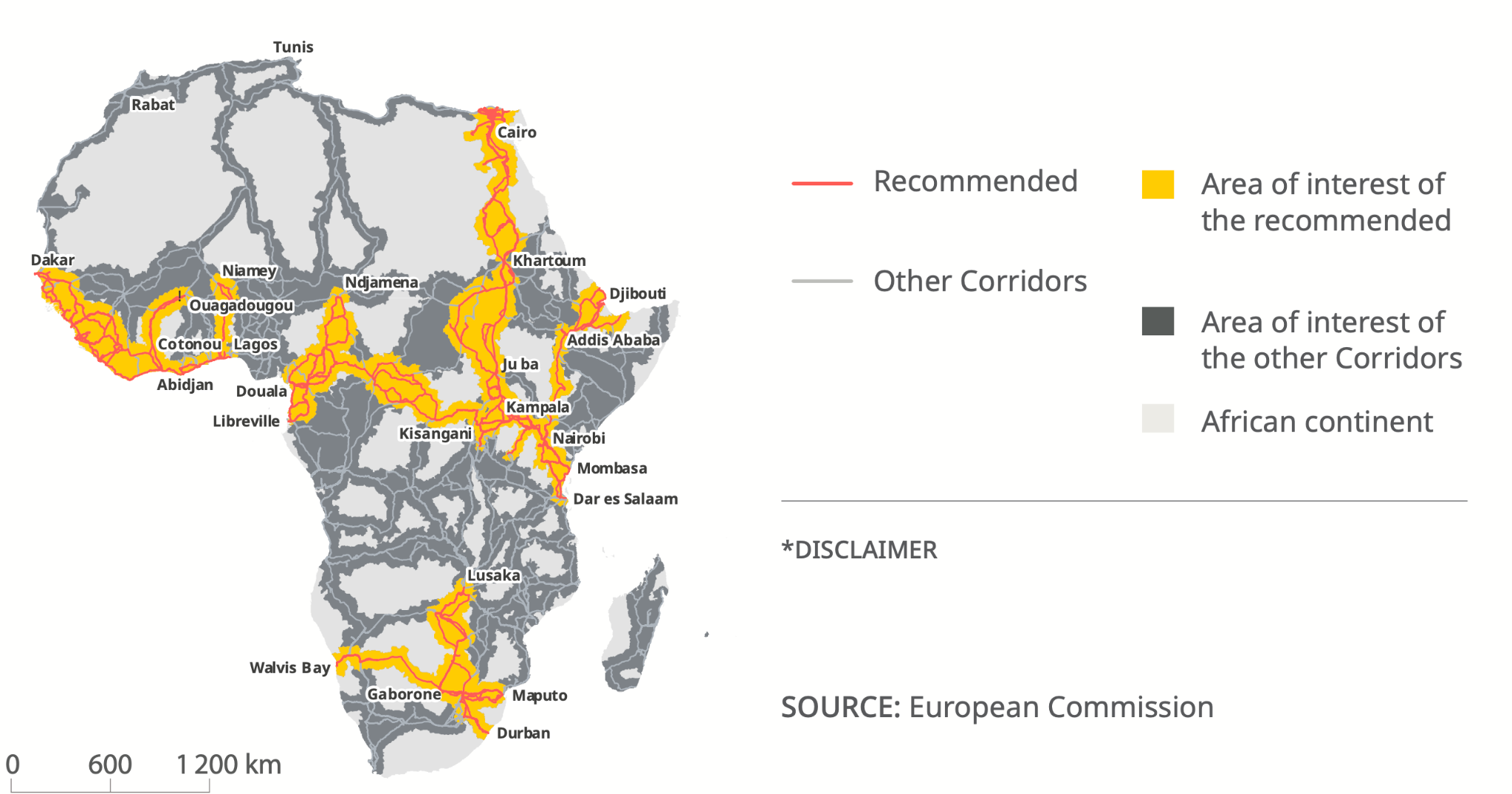

Image 1: The proposed Global Gateway corridors in Africa

Source: Global Gateway EU/Africa Investment Package 2023

Spanning across three mega-corridors—the North-Central-East Africa (NCEA) strategic corridor, the West Africa strategic corridor and the South Africa strategic corridor—these infrastructure investments, totalling almost US$ 165 billion, are aimed at countering deep-seated Chinese presence in the continent as well as making up for the EU’s decades of limited engagement with African markets, as Beijing raced ahead.

These mega-corridors are symbolic of the EU’s bid for further economic integration by not only building transport and economic corridors but also by providing African people access to low-interest/interest-free credit lines along these corridors. While the NCEA corridor spans three regions—East, Central, and North Africa, the remaining two corridors are aimed at enhancing region-specific connectivity, in the port-dense regions of west and south Africa. This article analyses the western and southern strategic corridors and provides geoeconomic and strategic implications of these proposed corridors.

West and South African strategic corridors—all roads lead to the ports

The Global Gateway corridors in West Africa boast an impressive investment portfolio detailing roads, bridges, highways, green energy projects, critical minerals mining and port infrastructure alongside enhancing digital connectivity through the ‘Global Gateway Digital Connectivity and Infrastructure Initiative’. Through these four corridors across 13 countries (see Table 1), the EU wishes to bolster logistical connectivity between the regional ports across West Africa and the hinterland regions of north Nigeria, Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso—all resource-rich but landlocked countries (see Image 1). As a result, all four corridors in the region lead to ports from Nigeria’s Lekki port in the south to Senegal’s Ndayane port in the northwest. These connectivity initiatives also envisage support for the ECOWAS’ stated goal of emerging as a regional energy transport hub. Besides enhancing logistical capabilities, the GG also aims to positively impact critical economic sectors such as mining, energy exploration, railways, mineral processing and social infrastructure through investments in sustainable energy and green infrastructure investments coupled with communication infrastructure.

| Table 1: Proposed GG investments in West and South Africa by the EU – ODA | |||

| Corridor | Region | Potential beneficiaries | Major economic sectors benefiting |

| Abidjan-Lagos | West Africa | Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria | Green energy infrastructure, transport infrastructure, railways, sustainable mining, communications infrastructure |

| Abidjan-Ouagadougou | West Africa | Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso | Transport infrastructure, communications infrastructure |

| Praia/Dakar-Abidjan | West Africa | Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde | Precious metals extraction, mineral processing, energy infrastructure, transport infrastructure, communications hardware |

| Cotonou-Niamey | West Africa | Benin, Niger | Gold mining, mineral processing, sustainable mining, transport infrastructure |

| Maputo-Gaborone-Walvis Bay | South Africa | Mozambique, South Africa, Eswatini, Botswana, Namibia | Critical minerals, mining, digital infrastructure, social infrastructure |

| Durban-Lusaka | South Africa | South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia | Critical minerals, sustainable mining, mineral processing, digital infrastructure |

| Total number of corridors: 6 | Regions involved: 2 | Countries involved: 19 | Total number of sectors benefiting: 13 |

Source: Global Gateway Investment Dossier

While Europe’s aims and initiatives in West Africa and the NCEA corridor countries have been expansive, in the South African region, the GG seems to be moving cautiously and strategically. Here, the EU \has initiated only two corridors aiming to develop the Walvis Bay, Maputo and Durban ports and the area lying in between (see Table 1, then Image 1). Walvis Bay is Namibia’s only deep-sea port and has piqued China’s interest in the past, for building a multi-purpose port there. Walvis Bay, in addition to Durban and Maputo ports, serves as a connector to global markets for the landlocked African countries of Central Africa and South Africa. These ports also control critical shipping lanes in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and are unexplored regions for blue economy sectors such as deep-sea mining, oil exploration, and commercial fishing. The EU’s foray into infrastructural diplomacy in this region is aimed at securing these critical shipping lanes, ports and blue economy sectors for European markets.

EU’s strategic imperatives for the Global Gateway

Besides aiming to build connectivity infrastructure across the regions, the Global Gateway also has the stated objective of mitigating geopolitical risks from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI’s) steady economic engagement with these 19 countries (see Table 1). The EU looks at China as a ‘systemic rival’ yet an important commercial partner. For decades, the EU and its Western allies cultivated China as a one-stop destination for all their overseas manufacturing bases and industrial imports, which in turn, and over time made the West overtly dependent on China. Daily trade between the EU and China in 2022 amounted to US$ 2.43 billion, with the EU running a continually widening goods trade deficit at US$ 441.56 billion—touted by its ambassador to China as the ‘largest ever in the history of mankind’. The Global Gateway is the EU’s bid to diversify its supply chains and de-risks its economy to external shocks through gradual decoupling with the Chinese economy, as Beijing’s posturing on the global stage turns increasingly aggressive.

China became cognizant of the geostrategic relevance of infrastructure development in international relations when it launched the BRI in 2013. After decades of disbursing decentralised aid, the Global Gateway is Brussels’ bid to foray into developmental and infrastructure diplomacy by augmenting regional connectivity across the developing world. Empercially researched corridors, built through transparent financial aid aimed at promulgating development across Africa, put forth an attractive alternative to Beijing’s ‘One Belt, One Road’. Brussels is presented with a unique opportunity to create developmental impact by deepening infrastructure collaboration with partner countries and promulgating a developmental worldview based on democratic values, good governance, sustainability and equal partnerships. Such large-scale initiatives will also require working with like-minded democracies. Brussels hopes that this initiative will serve as a rallying point to unite the global democracies for closing the infrastructure development gap in the developing world and against China’s erratic, commercial, and exploitative lending spree across the Global South.

Conclusion

Brussels is uniquely placed as far as infrastructural diplomacy goes. It has recently concluded connectivity partnerships with India, Japan, and Australia. It also intends to pursue a connectivity partnership with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, building on the 2020 Ministerial Declaration. The Global Gateway in Africa is another link in the chain of global connectivity initiatives the EU wishes to build, for energy value chains impervious or at least resilient to external shocks.

Prithvi Gupta is a Junior Fellow in the Strategic Studies Programme, Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.