Sectoral analysis

Services activities accounted for the largest share of the enterprise population within the EU‘s non-financial business economy when analysed at NACE Rev. 2 section level for 2021: almost one-fifth (18.9 %) of the 31.0 million enterprises in the EU’s business economy were classified to distributive trades (motor trade, wholesale trade and retail trade), while close to one in six (15.5 %) were in professional, scientific and technical activities — see Figure 1. Many business services have benefitted from outsourcing, which may explain, in part, the structural shift towards services. Human health and social work activities is ranked third among the services activities, accounting for (7.4 %) of the EU’s business economy, with 2.3 million enterprises.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

The non-financial business economy workforce (persons employed) reached over 156.1 million in 2021 in the EU, and generated a total of €9 323 billion of gross value added at factor cost.

Among the NACE Rev. 2 sections within the business economy, manufacturing was the largest in terms of value added: Over 2.1 million manufacturing enterprises in the EU generated approximately €2 221 billion of value added in 2021, while providing employment to 29.7 million persons. Distributive trade enterprises had the second largest share of employment: these enterprises provided employment to over 29.5 million persons and generated €1 508 billion of value added. Financial and insurance activities had the third highest value added (€957.4 billion) but only the tenth largest workforce (4.9 million persons). Professional, scientific and technical activities had the forth highest value added (€681.8 billion) and only the sixth largest workforce (11.6 million persons), behind administrative and support services (13.6 million persons), construction (13.4 million persons) and human health and social work activities (13.1 million persons).

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

Figure 2 contrasts the value added and employment contributions of the various sectors to the business economy totals. The industrial activities of manufacturing; electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; water supply, waste and remediation and mining and quarrying contributed more in terms of value added than employment to the overall business economy, indicating an above average apparent labour productivity. This was also the case in some of the service activities, namely financial and insurance activities, which had the highest apparent labour productivity overall, as well as information and communication services and as real estate activities. By contrast, the construction sector and a number of services — notably accommodation and food services and administrative and support services (which includes cleaning and security services, as well as employment services such as the provision of temporary personnel)— reported relatively low levels of apparent labour productivity. Distributive trade also presents a lower share in value added than employment; however, it represents the second largest contributor after manufacturing in terms of both value added and employment. It should be noted that the employment data presented are in terms of head counts and not, for example, full-time equivalents, and there may be a significant proportion of persons working part-time in some of these service activities, which may explain, at least to some degree, their relatively low levels of apparent labour productivity.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

Varying rates of part-time work also help explain, in part, the considerable differences in average personnel costs within the business economy of the EU, as shown in Table 3. Average personnel costs in the EU peaked in the financial and insurance activities at €55 600 per employee in 2021 and were slightly lower for the electricity, gas steam and air conditioning supply sector (€49 400 per employee) and information and communication (€47 900 per employee). Average personnel costs for the electricity, gas steam and air conditioning supply sector were more than four times as those recorded for accommodation and food services (€13 500 per employee) and more than twice those recorded for administrative and support service activities (€21 800 per employee), education (€23 600 per employee), arts, entertainment and recreation (€24 600 per employee) and distributive trades (€26 700 per employee).

The variation in average personnel costs was even more marked between EU Member States: for example, within the manufacturing sector average personnel costs ranged (among those EU Member States for which data are available) by a factor of almost 10, from a high of €74 500 per employee in Denmark to a low of €9 900 per employee in Bulgaria.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

The influence of part-time employment is largely removed in the wage adjusted labour productivity ratio, which shows the relation between average value added per person employed and average personnel costs per employee (see Figure 3). This ratio was particularly high (388 %) in the EU for the electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply activities in 2021, as well as in financial and insurance activities (352 %) and real estate activities (346 %). The wage adjusted labour productivity ratio fell below 150 % in several services activities: professional, scientific and technical activities, human health and social work activities, other personal service activities, repair of computers, personal and household goods and in education.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

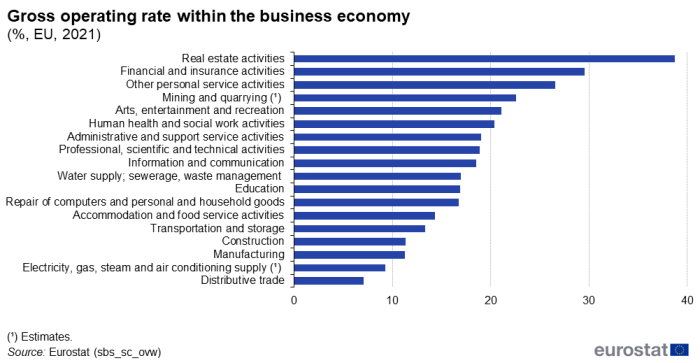

The gross operating rate shown in Figure 4 relates the gross operating surplus (value added less personnel costs) to the level of turnover and in this way indicates the extent to which sales are converted into gross operating profit (before accounting for depreciation or taxes). Due at least in part to the very high level of sales inherent in wholesaling and retailing, the EU distributive trades sector displayed the lowest gross operating rate across NACE sections, at 7.1 % in 2021. Capital-intensive activities (such as real estate activities; 38.8 % and financial and insurance activities; 29.6 %) tended to have high gross operating rates as the gross operating surplus by definition does not take account of financial or extraordinary costs related to capital expenditure.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

Size class analysis

Structural business statistics can be analysed by enterprise size class (defined in terms of the number of persons employed). The overwhelming majority (99.8 %) of enterprises active within the EU’s non-financial business economy in 2021 were micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) — some 30.9 million — together they contributed 52.5 % of the value added generated within the EU’s non-financial business economy. More than 9 out of 10 (94.1 %) enterprises in the EU were micro enterprises (employing less than 10 persons) and their share of value added within the non-financial business economy was considerably lower, around one-fifth (19.2 %).

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

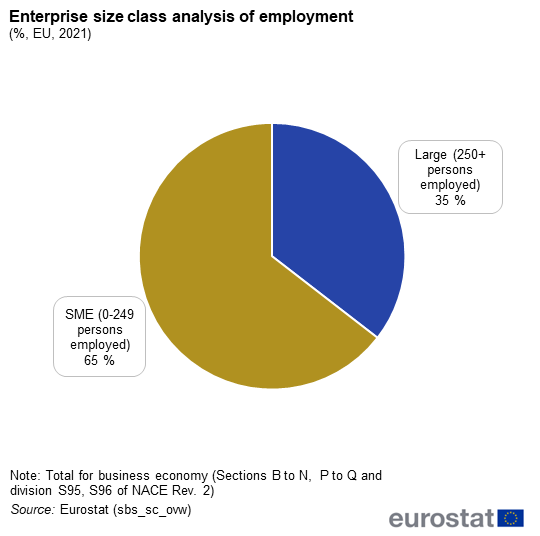

Perhaps the most striking phenomenon of SMEs is their contribution to employment. Around two-thirds (64.5 %) of the EU’s non-financial business economy workforce was employed in an SME in 2021. Some 20.2 million persons worked in SMEs in the distributive trades sector, 15.3 million in manufacturing and 11.7 million in construction; together, these three activities provided work to around 47.3 % of the non-financial business economy workforce in SMEs.

In 2021, micro enterprises in the EU employed more people than any other enterprise size class in more than half of the service sectors (at the section level of detail). This pattern was particularly pronounced for real estate activities, the repair of computers, personal and household goods and other personal service activities where an absolute majority of the workforce worked in micro enterprises. By contrast, for mining and quarrying as well as electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply and water supply, waste and remediation, financial and insurance activities and administrative and support service activities, large enterprises employed more than half of the workforce, as they also did in administrative and support service activities.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

The contribution of SMEs to total value added within the EU’s non-financial business economy was lower than their contribution to total employment, resulting in a lower level of apparent labour productivity; this situation was particularly clear in arts, entertainment and recreation, manufacturing and information and communication services. However, the exceptions were financial and insurance activities; administrative and support service activities, as well as electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

Business demography

Business demography statistics are presented in Table 4, which shows enterprise birth and enterprise death rates as well as the average size of newly born enterprises in terms of their employment. There are significant changes in the stock of enterprises within the business economy from one year to the next, reflecting among other things the level of competition, entrepreneurial spirit and the business environment.

Eurostat publishes detailed Business demography statistics compiled along the requirements of the new framework for European Business Statistics (EBS). Several improvements enhance the data’s capacity for analysis of the activity of enterprises in the EU, in particular for high-growth and young high-growth enterprises (also known as gazelles). The data now cover more economic activities, e.g. within services (education; human health and social work activities; arts, entertainment and recreation) and financial and insurance activities. Moreover, regional Business demography statistics are now available for all EU countries.

In 2021, the rate of enterprise births in the EU was 10.7 %. Among the EU Member States it ranged from 3.1 % in Estonia and between 6.0 and 7.8 % in Austria, Greece, Belgium and Germany to 13.0 % in Latvia, 14.4 % in Portugal and Malta, 16.2 % in France and 20.2 % in Lithuania. The improved coverage of Business demography statistics shows the dynamic of the service economy, e.g. for ‘education’ or ‘arts, entertainment and recreation’ where, in both cases, birth rates were above 10 % in two out of three EU countries (18).

The average employment size of newly born enterprises in 2021 varied between 0.4 persons in the Netherlands and 2.3 persons in Lithuania. At the EU level, the average size of newly born enterprises was 1.1 persons.

In 2021, enterprise death rates, which are based on provisional data, were particularly low in Greece (2.2 %), Belgium (3.6 %) and the Netherlands (4.2 %), ranging up to 22.6 % in Lithuania and 23.4 % in Estonia. At EU level, the preliminary rate of enterprise deaths stood 8.5 %.

In most EU countries more companies were created than dissolved. The exceptions to this were Estonia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Poland, Denmark and Germany where the number of enterprises dissolved surpassed the number of companies created.

Source: Eurostat (bd_l_form)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Eurostat’s structural business statistics describe the structure, conduct and performance of economic activities, down to the most detailed activity level (several hundred sectors). Without this structural information, short-term data on the economic cycle would lack context and would be more difficult to interpret.

Coverage, units and classifications

Structural business statistics cover the ‘business economy’, which includes industry, construction and many services (NACE Rev. 2 sections B to N, P to R as well as division S95 and S96). Structural business statistics do not cover agriculture, forestry and fishing, nor public administration.

Structural business statistics describe the business economy through the observation of units engaged in an economic activity; the unit in structural business statistics is generally the enterprise. An enterprise carries out one or more activities, at one or more locations, and it may comprise one or more legal units. Enterprises that are active in more than one economic activity (plus the value added and turnover they generate, the people they employ, and so on) are classified under the NACE heading corresponding to their principal activity; this is normally the one which generates the largest amount of value added.

NACE Rev. 2 was adopted at the end of 2006, and implemented in structural business statistics from the 2008 reference year. Compared with NACE Rev. 1.1, this has enabled a broader and more detailed set of information to be compiled on services, while also updating the classification to identify new areas of activity better.

Starting with the reference year 2021, Structural Business Statistics are compiled under the legal basis of the EU regulation 2019/2152 on European business statistics and its implementing act, EU regulation 2020/1197 on technical specifications and arrangements.

Size class and regional analysis

Structural business statistics are also available with an analysis by region or by enterprise size class. In structural business statistics, size classes are defined by the number of persons employed, except for specific data series within retail trade activities where turnover size classes are also used. A limited set of the standard structural business statistics variables (for example, the number of enterprises, turnover, value added and persons employed) is analyzed by size class, mostly down to the three-digit (group) level of NACE. For statistical purposes, SMEs are generally defined as those enterprises employing fewer than 250 persons. The number of size classes available varies according to the activity under consideration. However, the main groups used in this article are:

- small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): with less than 250 persons employed, further divided into;

- micro enterprises: with less than 10 persons employed;

- small enterprises: with 10 to 49 persons employed;

- medium-sized enterprises: with 50 to 249 persons employed;

- large enterprises: with 250 or more persons employed.

Structural business statistics contain a comprehensive set of basic variables describing business demographics and employment characteristics, as well as monetary variables (mainly concerning operating income and expenditure, or investment). In addition, a set of derived indicators has been compiled: for example, ratios of monetary characteristics or per head values.

Business demography

Business demography are statistics about, amongst other things, the birth, survival (followed up to five years after birth) and death of enterprises within the business population. It reports changes in the stock of enterprises within the business economy from one year to the next, reflecting among other things the level of competition, entrepreneurial spirit and the business environment. Within this context the following definitions apply.

- Enterprise birth amounts to the creation of a combination of production factors, with the restriction that no other enterprises are involved in the event. Births do not include entries into the business population due to mergers, break-ups, split-offs or restructuring of a set of enterprises, nor do the statistics include entries into a sub-population that only result from a change of activity. The birth rate is the number of births relative to the stock of active enterprises.

- Enterprise birth rate: number of enterprise births in the reference period divided by the number of enterprises active in that same period.

- Enterprise death amounts to the dissolution of a combination of production factors, with the restriction that no other enterprises are involved in the event. An enterprise is only included in the count of deaths if it is not reactivated within 2 years. Equally, a reactivation within 2 years is not counted as a birth.

- Enterprise death rate: number of enterprise deaths in the reference period divided by the number of enterprises active in that same period.

- Average employment size of newly born enterprises: average number of persons employed in the reference period (t) among enterprises newly born in t divided by the number of newly enterprises born in t. If an enterprise was created later in the year with one self-employed person, the rounded annual average might be less than 1.

Context

In October 2010, the European Commission presented a Communication on a renewed industrial policy. An industrial policy for the globalisation era (COM(2010) 614 final) provided a blueprint that aimed to put industrial competitiveness and sustainability centre stage. It is a flagship initiative that forms part of the European Semester, and set out a strategy that aims to boost growth and jobs by maintaining and supporting a strong, diversified and competitive industrial base in Europe offering well-paid jobs while becoming less carbon intensive. The initiative put forward a strategic agenda and proposed some broad cross-sectoral measures, as well as tailor-made actions for specific industries, mainly targeting the so-called ‘green innovation’ performance of these sectors.

In January 2014, the European Commission adopted a further Communication titled For a European Industrial Renaissance. This set out key priorities for industrial policy, provided an overview of actions already undertaken within the context of the existing policy and put forward some new actions to speed up the attainment of objectives. This was followed in September 2018 by a consolidation of horizontal and sector-specific initiatives into the Communication Investing in a smart, innovative and sustainable industry — A renewed EU industrial policy strategy (COM(2018) 479 final), which aims to empower citizens, revitalise regions and encourage the adoption of new technologies to deliver the smart, clean and innovative industry of the future.

The internal market remains one of the EU’s most important priorities. The central principles governing the internal market for services were set out in the EC Treaty. This guarantees EU enterprises the freedom to establish themselves in other EU Member States and the freedom to provide services on the territory of another Member State other than the one in which they are established. The objective of the Services Directive 2006/123/EC of 12 December 2006, on services in the internal market, is to eliminate obstacles to trade in services, thus allowing the development of cross-border operations. It is intended to improve competitiveness, not just of service enterprises but also of European industry as a whole. It is hoped that the Directive will help achieve potential economic growth and job creation. By providing for administrative simplification, it also supports the better regulation agenda.

In April 2011, leading up to the 20th anniversary of the beginning of the single market, the European Commission released a Communication titled Single Market Act — twelve levers to boost growth and strengthen confidence (COM(2011) 206 final), aimed at improving the single market for businesses, workers and consumers. In October 2012, the European Commission proposed a second set of actions through the Communication titled Single Market Act II — Together for new growth (COM(2012) 573 final) to further develop the single market and utilise its untapped potential as an engine for growth. In October 2015, the European Commission presented a new single market strategy with the goal of delivering a deeper and fairer single market, Upgrading the Single Market: more opportunities for people and business (COM(2015) 550 final).

SMEs are often referred to as the backbone of the European economy, providing a potential source for both jobs and economic growth. In June 2008, the European Commission adopted a Communication on SMEs referred to as the Small business act for Europe (SBA). This aims to improve the overall approach to entrepreneurship, to irreversibly anchor the Think small first principle in policymaking from regulation to public service, and to promote SMEs’ growth by helping them tackle problems which hamper their development. The Communication sets out 10 principles which should guide the conception and implementation of policies both at EU and national level to create a level playing field for SMEs throughout the EU and improve the administrative and legal environment to allow these enterprises to release their full potential to create jobs and growth. It also put forward a specific and far reaching package of new measures including four legislative proposals which translate these principles into action both at EU and Member State level.

A review of the SBA was released in February 2011: it highlighted the progress made and set out a range of new actions to respond to challenges resulting from the financial and economic crisis. In doing so, it is hoped that the updated SBA will contribute towards delivering the key objectives of the Europe 2021 strategy — namely, smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. With this in mind, the European Commission launched a public consultation on the SBA to gather feedback and ideas on how the SBA could be revised in order to promote European policy support for SMEs and entrepreneurs during the period 2015-2021. This area of work is also supported by:

- the SME performance review, which provides a tool for monitoring and assessing the progress made in implementing the SBA, as well as a set of country factsheets reporting on SME developments in the EU Member States;

- the Green action plan Enabling SMEs to turn environmental challenges into business opportunities (COM(2014) 440 final), which aims to promote some of the opportunities that may arise for SMSs during the transition to a greener economy.