Self-employment: outline and latest developments

Two thirds of self-employed people are own-account workers, one third are employers

In the third quarter of 2021, the vast majority of people in employment in the EU were employees, i.e. 86.2 % among people aged 20-64. The biggest remaining part of employed people were self-employed people (13.2 % among people aged 20-64 at EU level). Greece (27.4 %), Italy (19.3 %) and Poland (18.4 %) recorded the highest shares of self-employment in total employment. By contrast, the lowest shares were found in Germany (7.6 %), Luxembourg (7.9 %), Denmark (8.1 %) and Sweden (8.7 %).

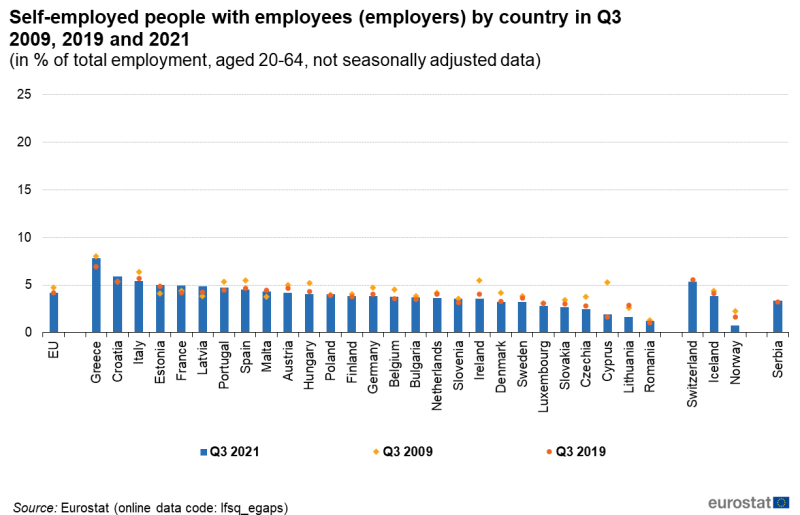

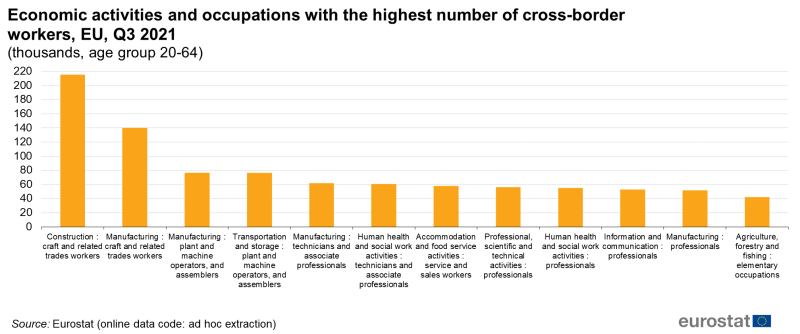

Self-employed persons can be divided into two categories, i.e. the self-employed persons with employees (employers) and the self-employed persons without employees (own-account workers), see Figure 1a and 1b respectively. In Q3 2021, more than two thirds of self-employed persons (68.2 %) in the EU were own-account workers while 31.8 % were employers. This last group accounted for 4.2 % of the total employment at EU level and for 5 % or more in Greece (7.8 %), Croatia (5.9 %), Italy (5.4 %), Estonia and France (both, 5.0 %). By contrast, less than 2 % of employed people were employers in Romania (1.2 %), Lithuania (1.6 %) and Cyprus (1.9 %). With regard to own-account workers, these stood for 9.0 % of the employed people at EU level and reached more than 13.0 % in Greece (19.6 %), Poland (14.3 %) and Italy (13.8 %) but less than 6 % in Germany (3.8 %), Denmark (4.8 %), Luxembourg (5.1 %), Sweden and Croatia (5.5 %).

The last category of employed people consists of contributing family workers. This professional status is relatively marginal at EU level (0.6 %).

Comparing the third quarter of 2021 with the same quarter of 2009 and 2019, the share of employers in total employment at EU level dropped by 0.5 p.p. from 2009 (from 4.7 % to 4.2 %) but remained stable compared with 2019. Cyprus (-3.3 p.p.), Ireland (-1.9 p.p.), Czechia (-1.3 p.p.) and Hungary (-1.1 p.p.) recorded the largest decreases from Q3 2009 to Q3 2021 while six EU Member states recorded an increase during the same period (Latvia: +1.1 p.p., Estonia: +0.9 p.p., Croatia, Malta and France: all +0.5 p.p. and Poland: +0.1 p.p.). Note that a break in the series exists between 2020 and 2021 due to a change of regulation for data collection (see the methodological notes at the bottom of the article).

Looking at the evolution for the own-account workers over the same period, their share in the total employment decreased from 10.2 % in Q3 2009 to 9.0 % in Q3 2021 (-1.2 p.p.). Over these 12 years, the share of own-account workers in the third quarter fell by more than 2 p.p. in Romania (-7.4 p.p.), Croatia (-6.5 p.p.), Portugal (-4.4 p.p.), Cyprus (-3.0 p.p.), Germany and Italy (both, -2.3 p.p.). By contrast, it increased in half of the EU Member States, although to a limited extent, as the highest increase was +2.2 p.p. in Latvia.

(in % of total employment, aged 20-64, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_egaps)

(in % of total employment, aged 20-64, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_egaps)

Self-employment more frequent among male workers, and aged 55-64

Figure 2 shows that, in the EU during the third quarter of 2021, men were more likely to be self-employed than women: 16.4 % of employed men were self-employed against 9.5 % for women. Considering the subcategories of self-employment, i.e. those with employees (employers) and those without employees (own-account workers), 73.7 % of self-employed women were own-account workers against 65.5 % of self-employed men. Thus, one third of self-employed men and one quarter of self-employed women were employers.

(in % of total employment, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_egaed) and (lfsq_esgaed)

The fact that self-employment is clearly more common among employed men than among employed women can be observed for every age group and educational attainment level (see Figure 2). Furthermore, there were more self-employed among employed people aged 55 to 64 compared with the other age groups (15-24 and 25-54). In Q3 2021, at EU level, 22.6 % of employed men aged 55-64 were self-employed against 15.8 % of employed men aged 25-54 and 4.5 % aged 15-24. Among employed women aged 55-64, 11.4 % were self-employed against 9.5 % aged 25-54 and 2.7 % aged 15-24. This pattern was observed for the total but also for each specific category of educational attainment level.

Differences in the professional status between the three levels of education i.e. low, medium and high level of educational attainment (see methodological notes for their description), were smaller than the ones observed for the age or gender groups. Nonetheless, self-employment appears to be more frequent among employed men and women aged 25-54 and aged 55-64 with a low educational attainment level than among employed people with a medium level. No such pattern can be deduced by comparing the high level with the other educational attainment levels.

The prevalence of being employers or own-account workers slightly differs from one category of education to another, especially for men. Regarding employers, men aged 55-64 with a high level of education were more likely employers than their counterparts with lower levels of education. By contrast, men aged 55-64 with a low level of education were more likely own-account workers.

Focus on employment by occupation and sector of activities

Most skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers are self-employed

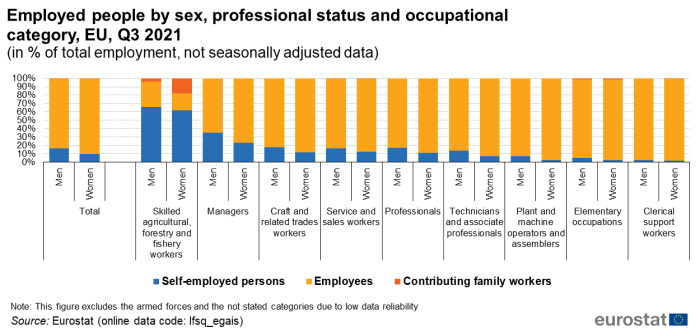

In Q3 2021, self-employment was the professional status of almost two thirds of skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery male workers (65.7 %) in the EU but also for female workers (61.7 %). Managers followed with more than one third (35.4 %) of male managers and almost one quarter (23.1 %) of female managers being self-employed (see Figure 3). By contrast, some occupations showed a very low level of self-employed people. Self-employment accounted for 7 % or less among the total clerical support workers (2.1 % for men and 1.7 % for women), people with elementary occupations (5.1 % for men and 2.1 % for women) and plant and machine operators and assemblers (7.0 % for men and 2.6 % for women).

Another relevant finding is that differences between self-employed men and women can be more or less broad depending on the occupational category. Managers showed the largest difference between men and women with a difference of 12.3 p.p.; they were followed by the technicians and associate professionals among which 13.9 % of employed men were self-employed but only 7.0 % of employed women, showing a gender gap of 6.9 p.p. Craft and related trades workers also showed a relatively large gap of 6.6 p.p. between men and women (17.9 % of employed men were self-employed against 11.4 % of women).

(in % of total employment, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_egais)

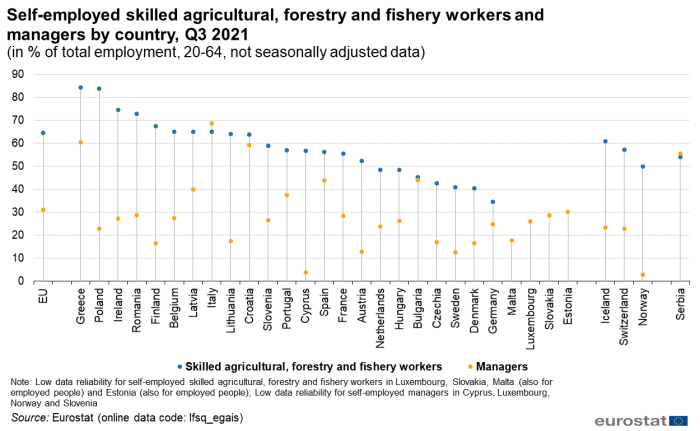

Figure 4 presents the share of self-employed skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers in the total employment as well as the share of managers by country. It is clearly visible that the weight of self-employment in the total employment varied significantly from one country to another in Q3 2021 for these two occupational categories. More than 70 % of the skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers were self-employed in Greece, Poland, Ireland and Romania while they accounted for less than 50 % in Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Czechia, Bulgaria, Hungary and the Netherlands. Moreover, more than two thirds of the managers were self-employed in Italy and about 60 % in Greece and Croatia. In contrast, self-employed only accounted for less than 20 % of the managers in Cyprus, Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Finland, Czechia, Lithuania and Malta.

(in % of total employment, 20-64, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_egais)

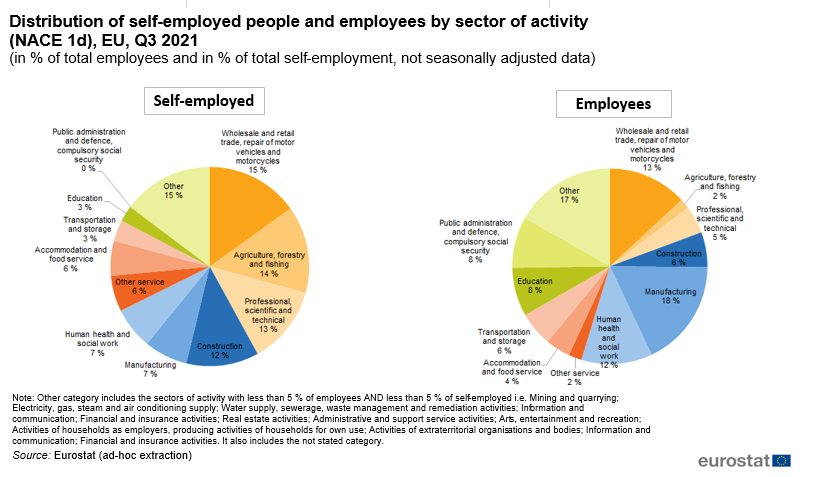

Largest differences between employees and self-employed in agriculture, forestry and fishing and in manufacturing

According to the most recent LFS data, more than half of the self-employed people in the EU (53.8 % exactly) are concentrated in four NACE sectors of activity as shown in Figure 5. The most popular sector among self-employed people is the sector of “wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles”, accounting for 15.1 % of the total self-employed people. By comparison, 13.1 % of the employees work in this sector. Ranking second, the sector of “agriculture, forestry and fishing” encompassed 14.2 % of the self-employed aged 20-64 but only 1.6 % of the total employees. More than one in 10 self-employed people worked in the sector of “professional, scientific and technical activities” (12.7 %), while 4.6 % of the employees were employed in this sector. The sector of construction accounted for 11.8 % of the self-employed people but only for 5.8 % of the employees. In contrast, 17.8 % of the employees were employed in the manufacturing sector (the largest sector for employees) against only 7.1 % of self-employed people.

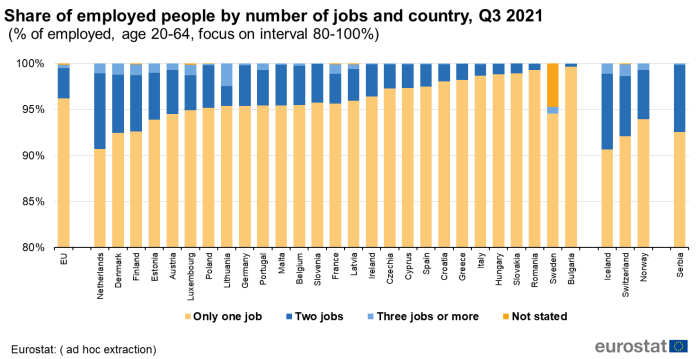

Profile of employed people with a second job

To complement the analysis of employment by professional status, the characteristics of employed people combining two, three or even more jobs can be looked at. In the third quarter of 2021, 3.3 % of employed people in the EU aged 20-64 had a second job, and 0.4 % had three jobs or more (see Figure 6). These percentages varied among countries: the Netherlands (9.3 %), Denmark (7.5 %), Finland (7.3 %), Estonia (6.1 %) and Austria (5.5 %) recorded the highest shares of people with at least two jobs (Figure 6). In contrast, the lowest shares were found in Bulgaria (0.4 %), Romania and Sweden (both 0.7 %) and Slovakia (1.1 %). Lithuania had the highest share of people having three jobs or more (2.5 %).

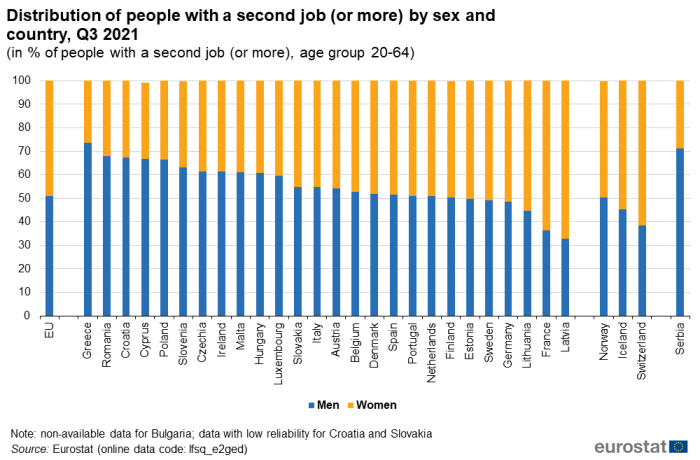

At EU level, the number of employed persons with at least two jobs is shared almost equally between men and women (50.8 % men and 49.2 % women in Q3 2021), see Figure 7. Nevertheless, the composition between men and women varies broadly among the different countries: from an extreme of 73.7 % of men (26.3 % of women) in Greece and 67.8 % of men (32.2 % of women) in Romania, to the opposite in Latvia with 32.8 % of men (67.2 % of women), France with 36.3 % of men (63.7 % of women), and Lithuania with 44.6 % of men (55.4 % of women).

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_e2ged)

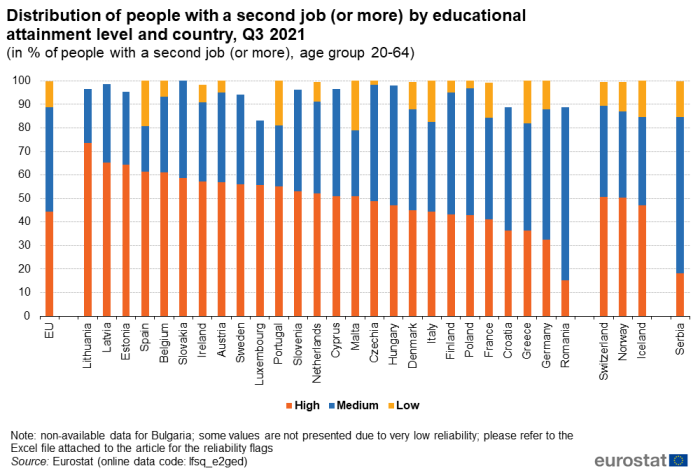

The EU aggregate presents a slightly higher share of people with a high educational level (44.5 %) than people with a medium level (44.3 %) among those with at least one second job (see Figure 8). At the same time, the share of people with a low level (11.0 %) is substantially lower.

In 15 EU countries, people with a high level of education represent the majority (more than 50 %) of people with a second job (or more), with shares ranging from 50.8 % in Malta to 73.7 % in Lithuania. In 6 other Member States, those with medium education were the majority, with shares ranging from 51.1 % in Hungary to 73.6 % in Romania. People with a low level of education were the least common group among those with at least one second job in all EU countries, with the slight exception of Spain (19.3 % with low versus 19.2 % with medium).

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_e2ged)

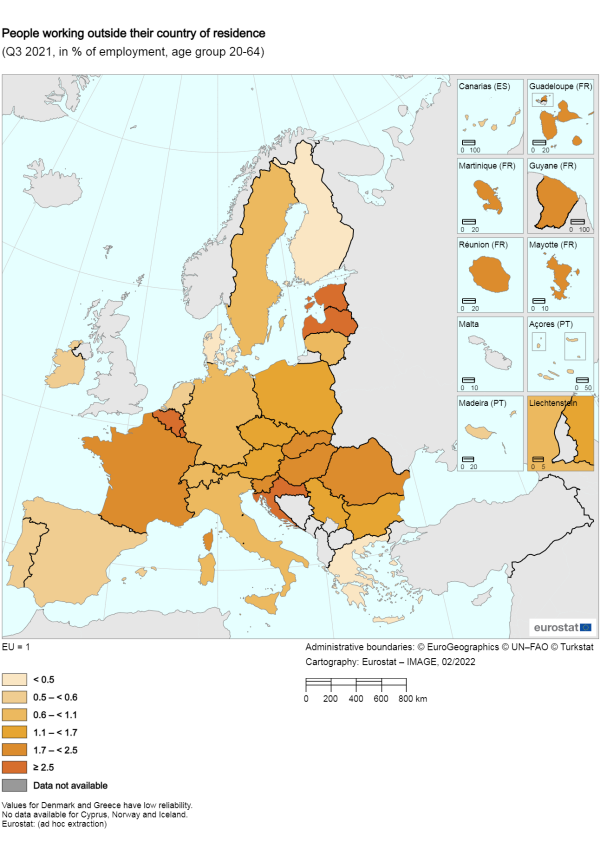

People working outside their country of residence

As over time more countries joined the EU and participated in joint projects and goals, more people have started working across the EU, finding jobs in countries different from their own.

In the third quarter of 2021, almost 2 million people have worked in another country outside their country of residence, accounting for 1.0 % of employed people aged 20–64 in the EU (see Map 1). Countries with the highest shares of EU cross-border workers among employed people were Estonia (2.9 %), Luxembourg (2.8 %), Belgium (2.7 %), Latvia and Croatia (both 2.5 %), and Slovenia (2.4 %). In contrast, countries in the EU with low mobility were Greece with 0.1 % of employed people working in another EU country, Denmark with 0.2 %, and Finland with 0.3 %.

In which occupations and economic activities are the most cross-border workers?

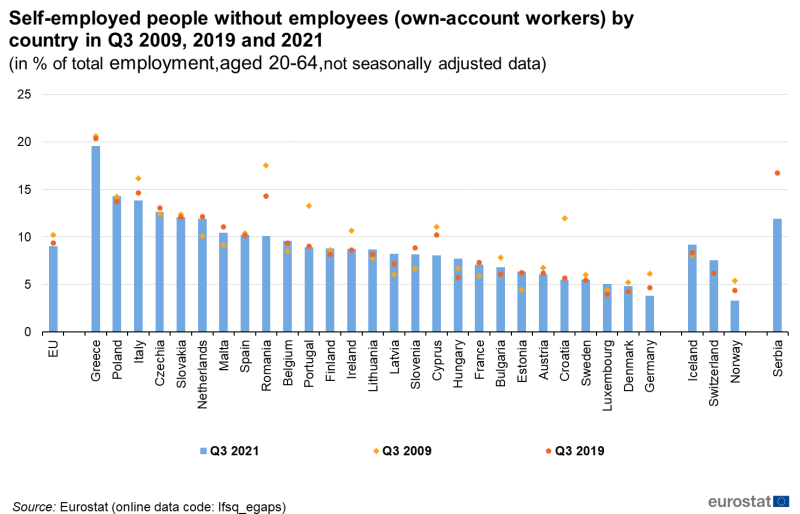

Across the EU, the ranking of economic activities crossed with occupations shows the most common groups of people who work outside their country of residence (see Figure 9). Among the top 12 categories, the most common is the craft and related trades workers in the construction sector with 215 100 workers. This is followed by the craft and related trades workers in the manufacturing sector with 139 800 workers. Plant and machine operators and assemblers in the manufacturing sector (76 700) and in the transportation and storage sector (76 500) rank third and fourth. Technicians and associate professionals in the manufacturing sector and in the human health and social work activities sector follow in the fifth and sixth positions of the ranking.

Professionals are also a very common group, among different sectors as professional scientific and technical activities, human health and social work activities, information and communication and manufacturing, with workers ranging respectively from 56.3 to 51.8 thousand. At the end of the top 12 ranking, there are the elementary occupations of the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector with 42.4 thousand workers who work in another country than their country of residence.

Men are more common in the first two categories craft and related trades workers in the manufacturing and construction sector. Instead, for women, the most common category is the technicians and associate professionals in the human health and social work activities sector.

Employment of first and second generation migrants by level of education and sex

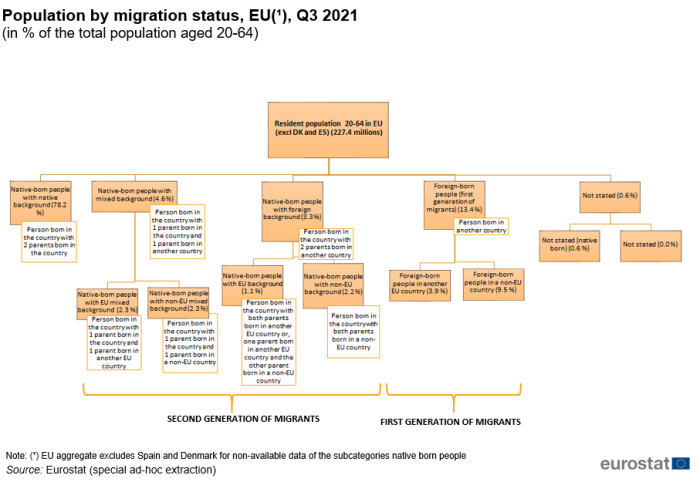

Starting from the first quarter of 2021, the EU-LFS provides quarterly indicators on the employment of second generation of migrants. The section “definition” below explains the various categories used in defining migration status presented in this section.

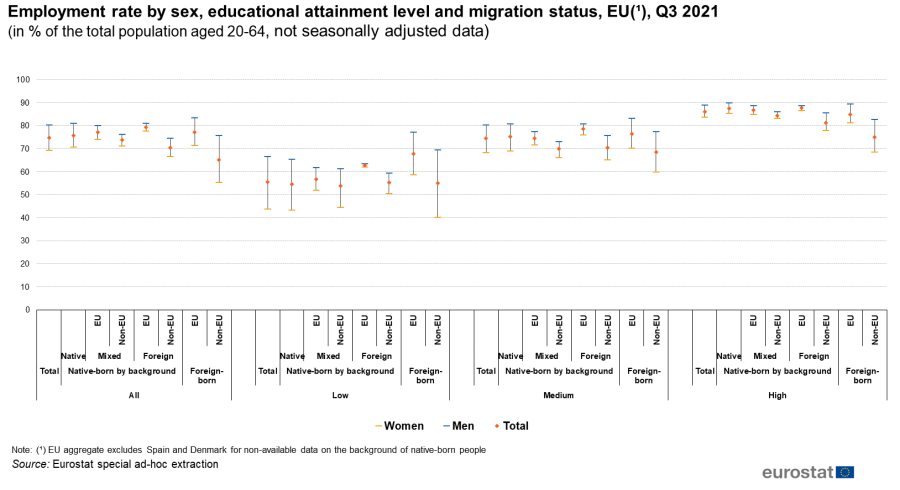

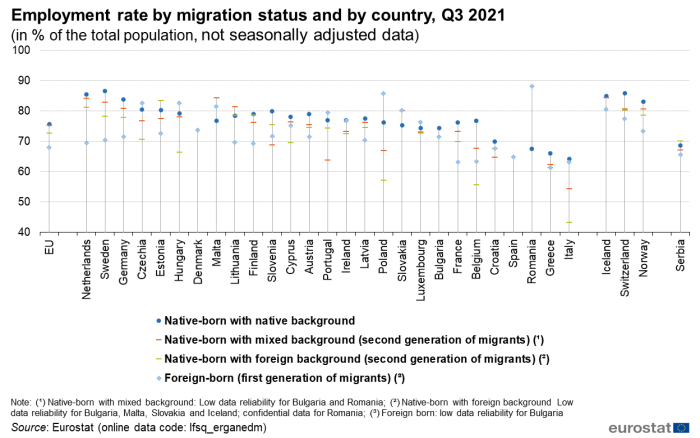

At EU level, the employment rate varied quite significantly according to the migration status (see Figure 10). Note that for the purpose of this analysis, Spain and Denmark were excluded from the calculation due to non-availability of data on native-born people. The highest employment rate was recorded for native-born people with a foreign EU background (i.e. people born in the country of residence with the two parents born in another EU country, or with one parent from another EU country and the other parent from a non-EU country). Indeed, almost 80 % of this population were employed in Q3 2021 (79.3 %). They were closely followed by native-born people with a mixed EU background, who recorded an employment rate of 77.1 %, and by people born in another EU country (77.0 %). Native-born people with a native background had an employment rate of 75.7 % whereas 73.7 % of native-born people with a mixed non-EU background were employed. Finally, employed people accounted for 70.4 % among native-born people with a foreign non-EU background, and slightly less than two thirds of people born in a non-EU country were employed in Q3 2021 (65.2 %).

Regardless of the migration status, the share of employed men was always higher than the share of employed women but the difference varied. The widest gender gap was reported for people born in a non-EU country (20.5 p.p.) resulting from a male employment rate of 75.6 % versus a female employment rate of 55.1 %. Ranking second were people born in another EU country with a gap of 12.1 p.p. between men and women, closely followed by native-born people with a native background who recorded a gender employment gap of 10.3 %. The second generation of migrants had the narrowest gender gaps: the native-born people with a foreign non-EU background recorded a difference of 7.9 p.p. between the employment rate of men and women, the native-born people with a mixed background showed a gender gap of 6.0 p.p. for those with a EU background and of 5.3 p.p. for those with a non-EU background. The category recording the narrowest gender gap was the native-born people with a foreign EU background (3.3 p.p.).

Considering people with a low educational attainment level, people who were born in another EU country registered the highest employment rate (67.8 %) in Q3 2021, followed by native-born people with a foreign EU background (62.8 %). The two lowest employment rates were recorded for native-born people with a native background (54.7 %) and those with a mixed non-EU background (53.8 %).

Among people with a medium or high educational attainment level, native-born people with a foreign EU background had the highest employment rate (78.4 % for the medium and 87.7 % for the high level of education).

In parallel, more than one third of people born in a non-EU country (37.6 %) had a low level of education, which is three times the share for native-born people with a mixed EU background (11.1 %). This high share of people with a low level of education might impact on the employment rate of people born outside the EU.

Crossing both factors, namely sex and education level, the widest gender gaps were reported by people with a low level of education, especially among people born in a non-EU country and native-born people with a native background. Both had differences in the employment rate of men and women of more than 20 p.p. (29.2 p.p. and 22.3 p.p. respectively).

Based on 21 EU Member States for which data on native-born people by background (without the EU/non-EU distinction) were available, almost one third of countries (namely six countries) followed the EU pattern with a higher employment rate for native born with a native background, followed by those with a mixed background, by those with a foreign background, and finally by people born in another country (see Figure 11). In seven other countries, the native-born people with a native background had also the highest employment rate but the other categories deviated compared with the EU level. Furthermore, in five countries the highest employment rate was recorded by the foreign-born people, while in one country both employment rate of native-born people with a native background and of foreign-born people were equal. In the remaining two countries for which all categories were available, the highest employment rate was reported by the second generation of immigrants.

(in % of the total population aged 20-64, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_erganedm)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on detailed quarterly survey results from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of the 27 EU Member States.

Country notes: (1) Spain and France have assessed the attachment to the job and included in employment those who have an unknown duration of absence but expect to return to the same job once the COVID-19 measures in place are lifted. (2) In the Netherlands, the 2021 quarterly LFS data remains collected using a rolling reference week instead of a fixed reference week, i.e. interviewed persons are asked about the situation of the week before the interview rather than a pre-selected week.

Definitions: The concepts and definitions used in the Labour Force Survey follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

The low educational attainment level refers to the attainment of lower secondary education, at most. The medium educational attainment level corresponds to at most upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education and the high level of educational attainment level to the attainment of tertiary education.

The migration status used in the current publication is defined as follows:

Main methodological changes introduced in 2021 by Regulation (EU) 2019/1700:

- persons on parental leave, and who are either receiving job-related income or benefits, or whose parental leave is expected to last 3 months or less, are counted as employed;

- persons raising agricultural products for own-consumption are excluded from employment;

- seasonal workers outside the season are classified as employed if they still regularly perform tasks and duties for the job or business during the off-season;

- people with a job or business who were temporarily not at work during the reference week but with strong attachment to their job are still considered as employed. In the particular context of the COVID-19 crisis and the measures applied to combat it, national specificities exist in the assessment of the job attachment;

- not employed people are considered searching for a job only if they use an active search method;

- questions to collect information on the actual working hours have been harmonised across countries through the use of a common model questionnaire;

- further harmonisation in the implementation of questions on different topics;

- modernisation of the survey at national level.

More information on this point can be found via the online publication EU Labour Force Survey, which includes eight articles on the technical and methodological aspects of the survey. The EU-LFS methodology in force from the 2021 data collection onwards is described in methodology from 2021 onwards while the one applicable until the 2020 data collection is presented in methodology until 2020. Detailed information on coding lists, explanatory notes and classifications used over time can be found under documentation.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in January and February 2020, with the first cases confirmed in Spain, France and Italy. COVID-19 infections have been diagnosed since then in all European Union (EU) Member States. To fight the pandemic, EU Member States have taken a wide variety of measures. From the second week of March 2020, most countries closed retail shops, with the exception of supermarkets, pharmacies and banks. Bars, restaurants and hotels were also closed. In Italy and Spain, non-essential production was stopped and several countries imposed regional or even national lock-down measures which further stifled economic activities in many areas. In addition, schools were closed, public events were cancelled and private gatherings (with numbers of persons varying from 2 to over 50) banned in most EU Member States.

The majority of the preventive measures were initially introduced during mid-March 2020. Consequently, the first quarter of 2020 was the first quarter in which the labour market across the EU was affected by COVID-19 measures taken by Member States.

In the following quarters of 2020, as well as 2021, the preventive measures against the pandemic were continuously lightened and re-enforced in accordance with the number of new cases of the disease. New waves of the pandemic began to appear regularly (e.g. peaks in October-November 2020 and March-April 2021). Furthermore, new strains of the virus with increased transmissibility emerged in late 2020, which additionally alarmed the health authorities. Nonetheless, as massive vaccination campaigns started all around the world in 2021, people began to anticipate improvement of the situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

The quarterly data on employment allows to regularly report on the impact of the crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic on employment. This specific article depicts employment in general and specifically by gender, age and level of educational attainment. Another article Employed people and job starters by economic activity and occupation focuses on the employed people and job starters by sector of economic activity and occupation.

Please note that in this exceptional context of the COVID-19 pandemic, employment and unemployment as defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) are not sufficient to describe the developments taking place in the labour market. In the first phase of the crisis, active measures to contain employment losses led to absences from work rather than dismissals, and individuals could not look for work or were not available due to the containment measures, thus not counting as unemployed. Only referring to unemployment might consequently underestimate the entire unmet demand for employment, also called the labour market slack, which is further analysed, with the evolution of the total volume of working hours, in the publication Labour market in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic.