- European businesses are far more likely than US firms to cite regulation as a major obstacle to doing business. As Europe searches for ways to boost economic growth and frets about its competitiveness, the EU needs to ensure its regulations encourage better productivity and more innovation.

- For decades, EU leaders have promised to improve law-making processes. These promises typically aim to ensure that regulations are evidence-based, made transparently, consulted on, and are as simple and targeted as possible. These are all important ways to ensure regulations have clearly defined goals, deliver those goals effectively and efficiently, and cause minimal unintended consequences. Europe has come a long way in this process. But there remains scope for significant improvement.

- Under its last two presidents, the European Commission has become a more political body. That role has helped the EU through recent crises. However, it also means the EU has lost one of its strengths: having a technocratic law-making body focused on designing laws based on evidence and good practice, and which is less beholden to short-term politics than the European Parliament and European Council. A more technocratic stance is also essential so that the Commission is perceived to be an impartial enforcer of EU laws – and so it can hold member-states to account when they do not implement those laws properly.

- If, as expected, Ursula von der Leyen wins a second term as Commission president, as part of her promise to focus on ‘competitiveness’, she should rebalance the Commission’s more political stance. The Commission needs to improve the credibility of its consultations – the process by which it invites stakeholders to comment on its proposals – to show it is driven as much by evidence as by politics. The Commission should also improve the consistency and rigour of its impact assessments.

- Regardless of the identity or agenda of its next president, the next Commission will likely still enjoy an historically high level of power and political independence. The better regulation agenda needs to reflect this by imposing more independent scrutiny and accountability on the Commission. The Regulatory Scrutiny Board has a good reputation for holding the Commission to account. But it could be more effective with more resources and institutional independence. The Commission should also consider ways to protect some of its important functions from the perception of politicisation – for example, with more internal checks and balances to ensure EU laws are enforced impartially and to ensure the Commission is prepared to force member-states to properly implement EU laws.

- The Parliament and the Council have even more work to do. As the Commission now provides less of a technocratic check on member-states and MEPs, the European Council and Parliament now must incorporate better regulation principles into their own practices. Leaving better regulation to the Commission is no longer an option. Unfortunately, neither member-states nor MEPs appear to systemically consider the Commission’s impact assessments when they review proposed laws, or assesses the impacts of their own proposed substantial amendments to Commission proposals. And the ‘trilogue’ process – where all three institutions negotiate the final shape of a new law – remains shrouded in secrecy, undermining much of the benefit of the Commission’s consultations and impact assessments.

- Better regulation is not just about the process of law-making. It is also about the substance, implementation and enforcement of EU laws. Laws need to be targeted, proportionate, predictable and clear – as does their enforcement and implementation. To achieve this, the Commission needs to worry less about maximising its powers and discretion: it should rely more on self-regulation and co-regulation, be prepared to ensure the consistent application of EU laws even when doing so is politically unpopular, and limit its own powers to change how laws are applied.

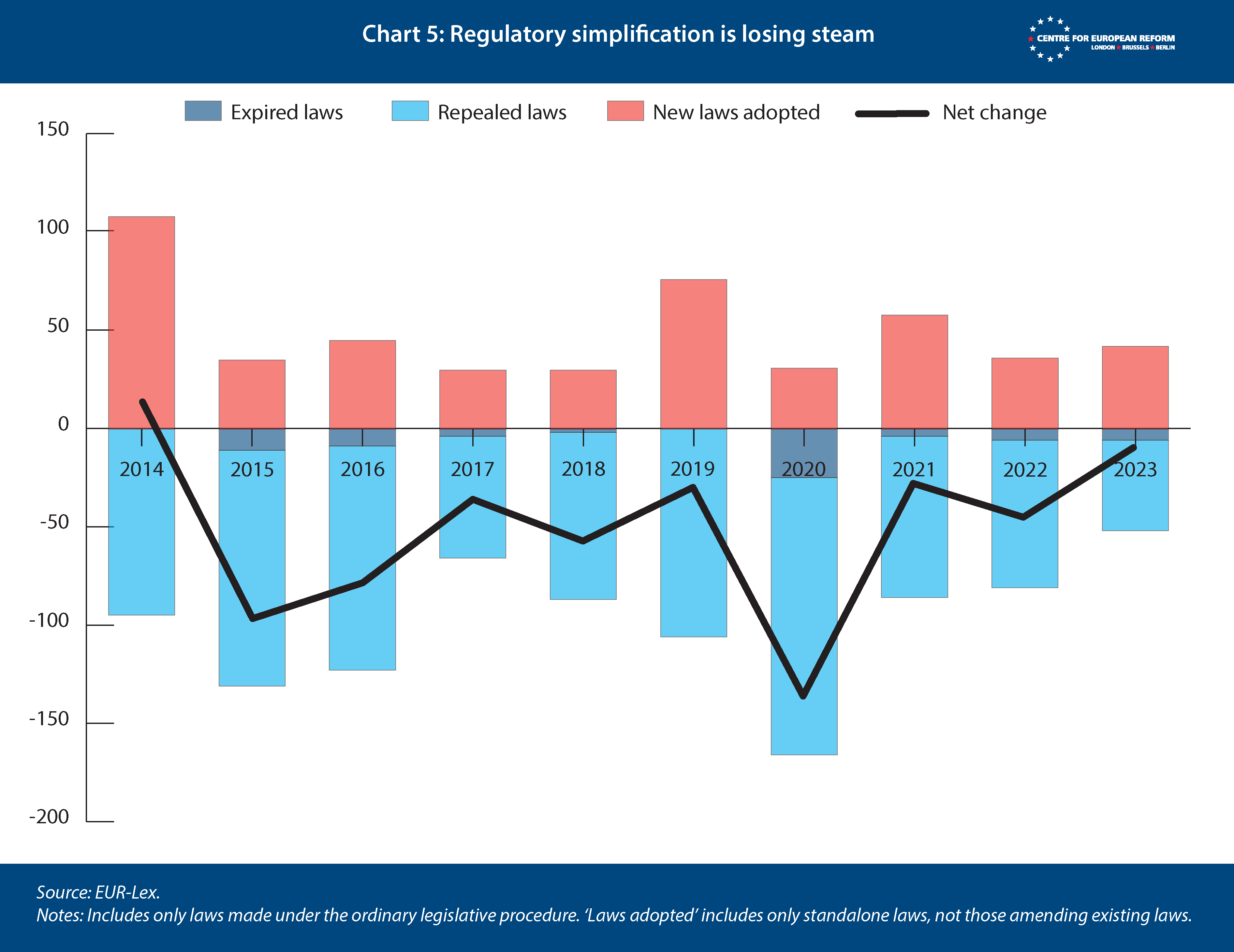

- Finally, the Commission needs to be more prepared to remove or simplify existing laws which are redundant, ineffective, or whose costs now outweigh the benefits. Despite worries about the EU’s economic performance, the Commission’s determination to cut regulatory burdens seems to be losing momentum. Its initiatives like ‘one in, one out’ need to move beyond a narrow focus on administrative costs and incorporate a broader assessment of how regulation impacts the European economy. The European Parliament and the European Council also need to make burden reduction a higher priority.

European businesses are far more likely than US firms to cite regulation as a major obstacle to doing business.1 Not only do firms find it hard to enter markets and expand in the EU, they also struggle to adapt and modernise their businesses. As Europe searches for ways to boost economic growth and frets about its competitiveness, the EU needs to ensure its regulations encourage better productivity and more innovation.

In recent decades, EU leaders have repeatedly committed to the ‘better regulation’ agenda. ‘Better regulation’ is a set of practices to ensure that EU regulations are evidence-based, made in a transparent and inclusive way, and are as simple and targeted as possible to reduce unnecessary burdens. Better regulation supports productivity and innovation by ensuring new laws are properly targeted and well-designed. That means unnecessary compliance costs are minimised, firms remain as free as possible to innovate and experiment, and regulation does not impose barriers on more productive firms mounting challenges to less productive incumbents.

Delivery has been underwhelming, however. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen started with strong commitments to better law-making but then had to spend much of her first term overseeing the EU’s response to many crises – such as the Covid pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the energy price crunch, the US and China’s use of industrial subsidies, and the need to respond to climate change. While member-states responded to these crises with surprising unity, they outsourced large parts of their response to the Commission, which has become more powerful than ever. The Commission president responded with an assertive and decisive style of leadership. This has had an understandable, but still negative, impact on the EU’s overall law-making rigour and its role as an enforcer of EU law.

The need to deal with unexpected crises is, however, only part of the reason for the Commission’s changing role. The last two Commission presidents have emphasised the institution’s political role over its technocratic one – Jean-Claude Juncker often spoke of the ‘political Commission’, and Ursula von der Leyen promised a ‘geopolitical Commission’. Changes in member-state governments mean that the current Commission is now less beholden to the European Council than ever before. And the Commission is being handed ever-new powers, such as the ability to tailor the path of member-states’ expenditure under the new Stability and Growth Pact.

Fast decision-making may work in solving crises, but is less suitable for tackling endemic problems facing the EU. For example, the EU could have acted earlier to address longer-term worries about Europe’s business model and its economic performance. To tackle long-term challenges, the Commission’s previous role as a more technocratic law-making body, which was more insulated from short-term politics and was focused on designing laws based on evidence, consultation and good practice, was indispensable. It formed a valuable counterbalance to the more explicitly political roles of the Parliament and Council in law-making. The Commission’s technocratic role was important for other reasons too: for example, to ensure impartial enforcement of EU laws and to ensure the Commission could hold member-states to account when they did not properly implement them. These are both essential steps to protecting Europe’s greatest economic asset, its single market, and promoting more competition and greater productivity across the Union.

To tackle long-term challenges, the Commission’s previous technocratic role and its focus on evidence, consultation and good practice, was indispensable.

The Commission now seems to recognise that responses to Europe’s biggest challenges – like delivering the green transition and enhancing Europe’s economic security – cannot be addressed in politically sustainable ways unless they are coupled with a plan to boost economic growth. In its final workplan, the current Commission promises to try to cut some red tape and streamline some regulatory obligations, especially for small and medium sized businesses. Von der Leyen has tasked former Italian prime minister and head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, to report on how to improve European competitiveness. And European Council President Charles Michel has tasked another former Italian prime minister, Enrico Letta, to report on the future of the single market.

The task of making substantial headway on improving EU law-making and the quality of EU laws, however, will belong to the next Commission. It is unclear whether von der Leyen’s recent focus on competitiveness is simply a means to build up support among member-states as she runs for a second term, or whether it represents a genuine shift towards more careful, inclusive and evidenced-based decision-making – one which focuses on the EU’s long-term interests. In any event, whatever the next president’s goals, the next Commission is likely to continue to enjoy significant power, political independence and a strong agenda-setting role. This needs to be matched by more independent scrutiny and accountability, and consideration of ways to protect the integrity and independence of some of the Commission’s most important functions.

The Parliament and the Council have even more work to do. While they are naturally more political bodies, they have made commitments to follow transparent and evidence-based law-making processes – but these promises remain largely undelivered. Their approach undermines many of the efforts made by the Commission to regulate more effectively.

The purpose of this policy brief is to propose politically viable steps that could help the EU reinvigorate the better regulation agenda. The paper first explains the EU’s progress in executing its ‘better regulation’ strategies. It then suggests steps to further improve the process of making future regulation, addresses a number of ways new laws could be strengthened, and looks at how existing laws could be more effectively reviewed.

The EU and better regulation

The EU has recognised the need to improve the quality of its laws for over 20 years, with calls for a better regulation strategy starting in the 1990s.2 Since then, the Commission has generally been at the frontier of international best practice, adopting practices to ensure law-making is democratic, transparent and based on the best available expertise. However, the need for such better regulation practices has grown more urgent as the powers of the EU, and in particular the Commission, have increased.

What is better regulation?

‘Good regulation’ is hard to oppose in principle, even if there are disagreements on the detail. Most people would accept that regulation is more likely to be ‘good’ if law-makers:

- are properly informed of evidence for and against proposals, and understand the benefits and costs of alternatives;

- design their proposals in ways that ensure their laws are effective, achieve their objectives efficiently, minimise costs and reduce the risk of unintended consequences; and

- keep the performance of existing regulations under review.

The ‘better regulation’ agenda has therefore focused on three elements.

The first is the law-making process – such as ensuring the impacts of proposals are set out, alternatives are considered, and stakeholders have a fair opportunity to comment on proposals and contribute their own evidence. Law-makers should consider the full range of options, and take the costs and benefits of each one into account. A process which is transparent, inclusive and evidence-driven is more likely to result in higher-quality law. At a minimum, it ensures law-makers are better informed.

Substance matters too. That does not mean ‘better regulation’ should pre-empt political choices, and it does not mean law-making should become a purely technocratic exercise. It is part of law-makers’ responsibility to make policy judgements, by managing trade-offs and uncertain facts. But better law-making can ensure that these policy judgements are implemented wisely: by ensuring that laws achieve their objectives in cost-effective and efficient ways, that the risk of unintended consequences is minimised, that legislation is targeted directly at the problem it is supposed to solve, and that it does not cause greater burdens than necessary. It also does not end when laws are passed. ‘Better regulation’ requires that laws are implemented and enforced consistently, transparently and credibly.

Well-designed regulation should not come at the expense of economic growth: the EU’s climate laws helped Europe become a global exporter in green technologies.

Finally, ‘better regulation’ incorporates the idea of regulatory reviews. Laws should not continue to pile up over time indefinitely. Instead, laws need to be reviewed so that they can be repealed or reconsidered if they have succeeded in their objective (and are therefore redundant), if they have failed to deliver the intended results, or if they have had unintended consequences which outweigh any positive impacts. This helps ensure that regulation continues to deliver results efficiently and effectively, and that the burdens that regulations impose are not ‘normalised’ and therefore forgotten.

Better regulation does not necessarily mean less regulation. After all, the EU’s most powerful economic strength – its single market, which since its launch in 1985 has boosted the bloc’s GDP by 6 to 8 per cent3 – is built entirely on regulation. The economic benefits of boosting EU integration further could reach €2.8 trillion per year.4 EU laws can benefit businesses by creating a single rule-book and allowing them to easily offer products and services across Europe – in turn promoting competition and improving productivity as money and resources are reallocated to the firms that are the most efficient and innovative. In the absence of EU rules, the reality would be a fragmented landscape of different regulations in different member-states, which businesses would find even more onerous. While he referred to his intention to run a ‘political Commission’, Commission president Juncker balanced this by emphasising ‘subsidiarity’: the idea that the Commission should only regulate where doing so would add value, and that the Commission should therefore regulate less. But more recently, EU law-makers have accepted the merits of EU-wide regulation. A 2018 task force, for example, recognised that, because of the value of deepening Europe’s single market, “there is EU value added in all existing areas of activity”.5

Well-designed regulation can have other benefits too. It can help steer markets towards particular outcomes – such as protecting consumers, achieving the EU’s climate goals, and protecting human rights – and in this way push European businesses to adopt new technologies or ways of doing business. This does not necessarily come at the expense of economic growth: the EU’s climate laws, for example, imposed challenges on European businesses in the short term, but have helped Europe become a global exporter in green technologies.6

Lastly, better regulation avoids privileging big business which may have the loudest voice and the most resources. By providing more rigour in the law-making process, so that impacts of initiatives are considered systematically instead of on an ad hoc basis, the better regulation agenda should result in more inclusive law-making. This should give greater weight to the interests of stakeholders like consumers and small businesses.

The development of better regulation in the EU

The EU’s commitments to better regulation have become more important as its law-making powers increased. Member-states have, over time, given the EU – and in particular the Commission – a much broader basis for legislating. Reforms and political realities have also turned the Union – and, again, the Commission particularly – into less of a technocratic body and into a more politicised one, tasked with handling crises which member-states could not, or would not effectively, handle on their own. This shift – with the Commission adopting both more law-making power and more politicisation – requires new steps to promote the quality and legitimacy of EU laws. These were previously better protected when the Commission operated as a more technocratic institution which could focus on careful assessment of evidence when taking decisions and was less concerned with short-term political considerations.

An increasing focus on better regulation has, for this reason, been an important counterbalance to other features of the EU’s evolution. The EU’s better regulation agenda has therefore evolved and strengthened over time. A 2001 Commission white paper was an important milestone.7 It prompted substantive reforms, including commitments by the Commission to consult more and to perform impact assessments (IAs).8

To further improve IAs, in 2006 the Commission set up an ‘Impact Assessment Board’, staffed part-time by senior Commission staff and tasked with independently scrutinising the quality of the Commission’s IAs.9 In 2009, the EU began to assess the impact of proposed laws on small businesses.10 A Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT) was launched in 2012, aiming to identify and cut unnecessary regulatory burdens, and the Commission committed to reviewing the existing regulatory regime in an area before proposing new laws.

An increasing focus on better regulation has been an important counterbalance to other features of the EU’s evolution.

Despite these measures, by the mid-2010s, public trust in the Commission started to decline due to its growing role. Businesses increasingly accused it of ‘mission creep’ and of issuing ‘diktats’ without properly considering stakeholders’ concerns. The EU’s response to economic and financial crises like the European debt crisis in 2009 was led by European heads of state, putting the Commission’s leadership and legitimacy in question.11

When Jean-Claude Juncker became European Commission president in 2015, he matched his attempt to create a ‘political Commission’ with countervailing measures aimed at showing the Commission understood the need for accountability and responsibility. He sought to cut unnecessary initiatives and launched a broader set of reforms to improve the Commission’s legitimacy. These reforms included restructuring the Impact Assessment Board into today’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB), which remained part of the Commission but with more board members hired from outside and a broader mandate. This recognised that, as the Commission began to be seen as less of a neutral arbiter, the EU needed new and more independent bodies to provide accountability. Juncker’s Commission also promised to consult more transparently and at more stages of the policy-making cycle, including at the inception stage of new initiatives. It also began preparing IAs for some delegated acts – instruments which the Commission can make to supplement or amend primary EU laws, for example to add necessary details (and which can sometimes change the original law agreed by Parliament and member-states substantially). However, many of these steps remained tentative: IAs for delegated acts, for example, remained (and remain to this day) a rarity.

When she took over as Commission president in 2019, Ursula von der Leyen continued to reflect the tension between the Commission’s more politically active role and a focus on better regulation to demonstrate restraint. She appointed Frans Timmermans, who had led work on better regulation in the Juncker Commission, as Executive Vice President. Her letters to her Commissioners, and her communication to the Commission staff on its working methods, emphasised better regulation.12 This included adopting a ‘one in, one out’ principle: the idea that for every new burden a legislative proposal adds, the Commission should seek to remove another. Her Commission also led reforms to simplify consultation processes and better integrate sustainability, digitisation and long-term strategic foresight into the Commission’s IAs. The Commission also replaced the low-profile REFIT programme with ‘Fit for Future’: a programme to help the Commission identify ways to simplify and modernise legislation and cut regulatory burdens. The Commission’s practices today are largely codified in its better regulation guidelines13 and its more detailed better regulation toolbox, which provides guidance, tips and best practice for Commission staff.14 Nevertheless, in light of the crises von der Leyen had to face, the political role of the Commission seems in recent years to have become more important than better regulation practices.

The Parliament and the Council have taken a less proactive role in improving EU law-making – despite their pivotal role in amending and approving Commission proposals. In 2003, the Parliament, Council and Commission agreed an inter-institutional agreement on better law-making.15 They promised to be more transparent and acknowledged that when Parliament and the Council propose substantial amendments to Commission proposals, those amendments need IAs too. That agreement had little impact, and so Juncker obtained a new inter-institutional agreement (IIA) in 2016.16 This also aimed to convince the Council and Parliament to act more transparently and properly assess substantial amendments. Yet, as explained below, while the Parliament has at least taken some steps towards better law-making, member-states in the Council have made very little progress.

Consultations and impact assessments

It seems likely that the next Commission president will be determined to focus on addressing the EU’s economic growth. This will require a more long-term approach than the Commission has adopted while it addressed recent crises. To do so, the Commission needs to be driven by evidence as much as politics. Since the Commission is unlikely to become significantly less political, it may have to rely more on external independent expertise.

Consultations should be objective tools to genuinely consider alternative policy options, not exercises used to validate pre-determined outcomes.

Take the most basic requirement of good regulation: that law-makers should understand the effects of their proposals. There are two steps fundamental to achieving this. The first is to conduct comprehensive evidence-gathering exercises, such as through consultation exercises with stakeholders. The second is to use that evidence to systematically assess the impacts of proposals. In both of these functions, the Commission could rely more heavily on a stronger and more independent RSB.

The role of the Commission

Consultations

The Commission generally does a good job of inviting stakeholders to comment on its proposals. The Commission consults with the public when it proposes new legislation. It also commonly solicits feedback at many more steps in the policy-making process – for example, when it prepares policy roadmaps, is considering whether or not to introduce a new law, when it proposes delegated or implementing acts, and when it reviews existing legislation and policies. The Commission has introduced minimum timeframes to ensure stakeholders have a fair opportunity to provide feedback – for example, public consultations for new initiatives backed by IAs should normally be open for at least 12 weeks, although consultation periods in other cases such as proposed delegated acts can be as short as four weeks. A dedicated EU website – ‘Have Your Say’ – helps stakeholders find open consultations and provide feedback.

A European Court of Auditors report in 2019 confirmed that the Commission’s consultations were generally of a high standard.17 However, there remain weaknesses in the Commission’s processes.

The risk of a more political Commission is that consultations are not seen as objective tools to genuinely consider alternative policy options, but rather exercises used to validate pre-determined outcomes made at a political level. As part of reforms in 2021, the Commission announced its desire to make consultation more “streamlined, inclusive and simpler” and more “focused”.18 The Commission now distinguishes between different types of consultation. These include formal ‘consultations’ (usually in the form of questionnaires), which it reserves for major initiatives; less structured ‘feedback’ opportunities on specific documents, such as calls for evidence; and targeted consultations with specific stakeholders for issues which are highly technical. While this can make consultation more efficient, it also gives the Commission a lot of discretion over how consultations should be conducted. This risks creating the perception that the Commission is treating consultation as simply a formal requirement, or wishes to minimise politically inconvenient feedback.

A number of specific issues illustrate this problem.

First, the quality of consultations varies greatly. Consultations may include leading questions and only allow input in the form of ‘multiple choice’ answers, or text boxes allowing responses to specific closed questions. This limits the ability of stakeholders to provide intelligent feedback, including on issues which may be highly relevant but which the Commission has not yet considered.

Second, while the Commission is trying to show more systematically how it has considered feedback,19 it often does so in a relatively crude way – for example, by responding to issues that are raised by the highest number of stakeholders, rather than those that raise the most material questions about the merits of the Commission’s proposals. Although the Commission is already stretched, it should nevertheless consider dedicating more resources to understanding, analysing and reacting to material feedback.

Third, consultations frequently take place with inadequate time to respond. The Commission has shortened consultation periods without obvious cause, or has held politically sensitive consultations over a holiday period. Smaller businesses find it especially difficult to respond to consultations held over short time periods, because they are more likely to lack dedicated government engagement teams who can identify and prepare responses quickly.

The Commission will need accountability to ensure its move towards flexibility and efficiency does not lead to fewer meaningful opportunities for feedback. To address this risk while the Commission’s roles and political function is increasing, internal processes will be insufficient. Instead, the Commission’s consultation strategy should be ‘validated’ by a body like the RSB.

The Board should check that a proposal for consultation is taking place early enough in the policy-making process so that it can meaningfully influence the Commission’s approach, that the consultation is properly designed to elicit appropriate feedback, that it has a reasonable deadline, and that the Commission has made reasonable decisions about who to consult with.

Impact assessments

Impact assessments

The Commission’s practice of preparing IAs has also improved over time – but businesses remain concerned that, like consultation, IAs can be influenced by the Commission’s political agenda.

Currently, the Commission increasingly prepares ‘inception impact assessments’ when proposals are being consulted on at the conceptual stage. These can sometimes be useful indicators of the Commission’s early thinking on a policy problem.

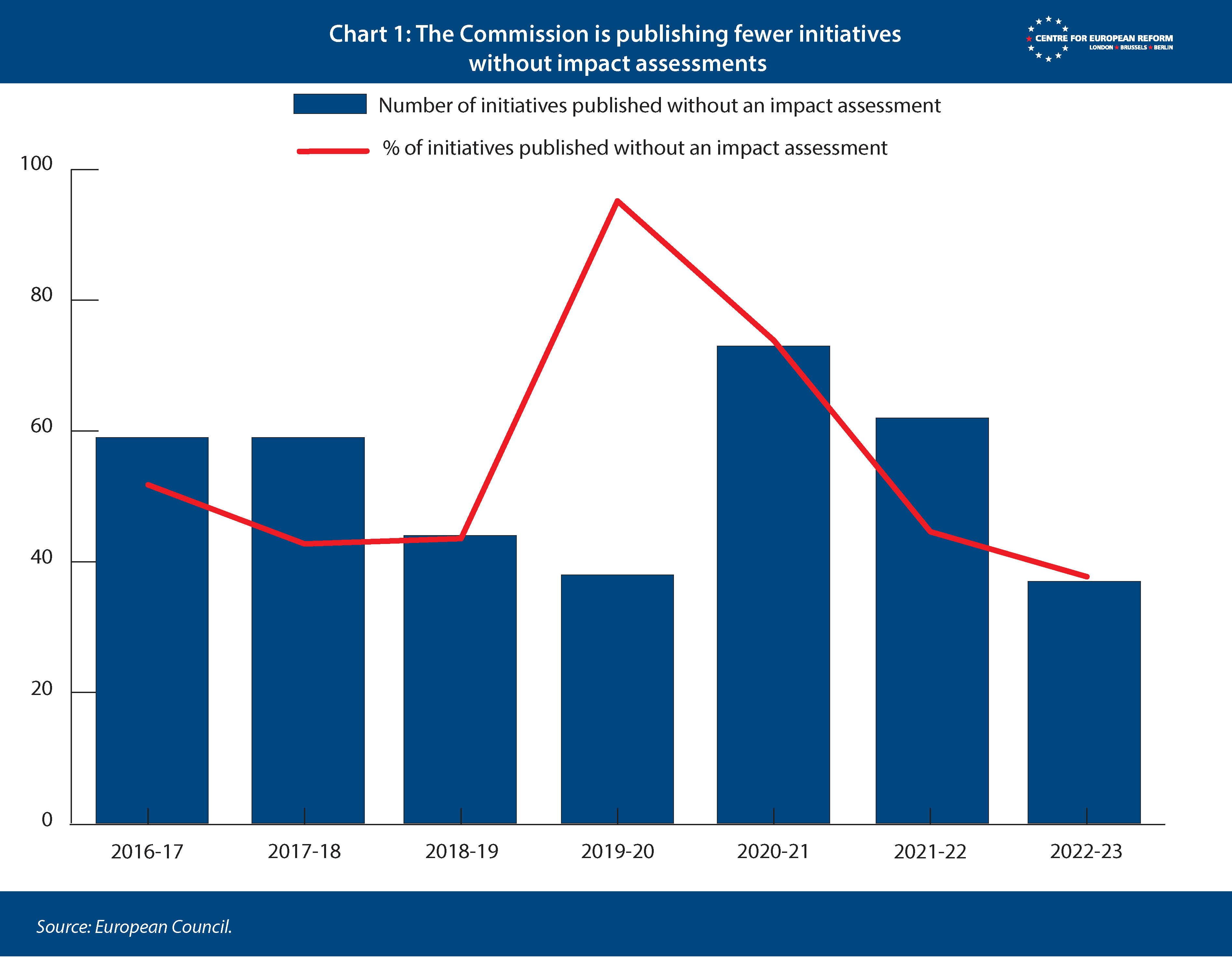

The Commission also prepares IAs once proposals are ready for full consultation. As Chart 1 shows, leaving aside the pandemic period when many initiatives were progressed urgently, the Commission is slowly publishing fewer legislative initiatives without an IA.21 However, there remains room for improvement. One problem is that the Commission too often cites urgency as a reason for not producing IAs, even for initiatives with obvious and very significant costs for European businesses, and where the need for urgency is not well established. These include the proposal for a Net-Zero Industry Act, a law which aims to boost the EU’s manufacturing of net-zero technologies, and the Forced Labour Directive, which aims to eliminate goods made using forced labour from the single market. The Commission still rarely prepares IAs for delegated acts. In the year ending May 2023, of 598 delegated acts and implementing measures, only three were accompanied by an IA.22

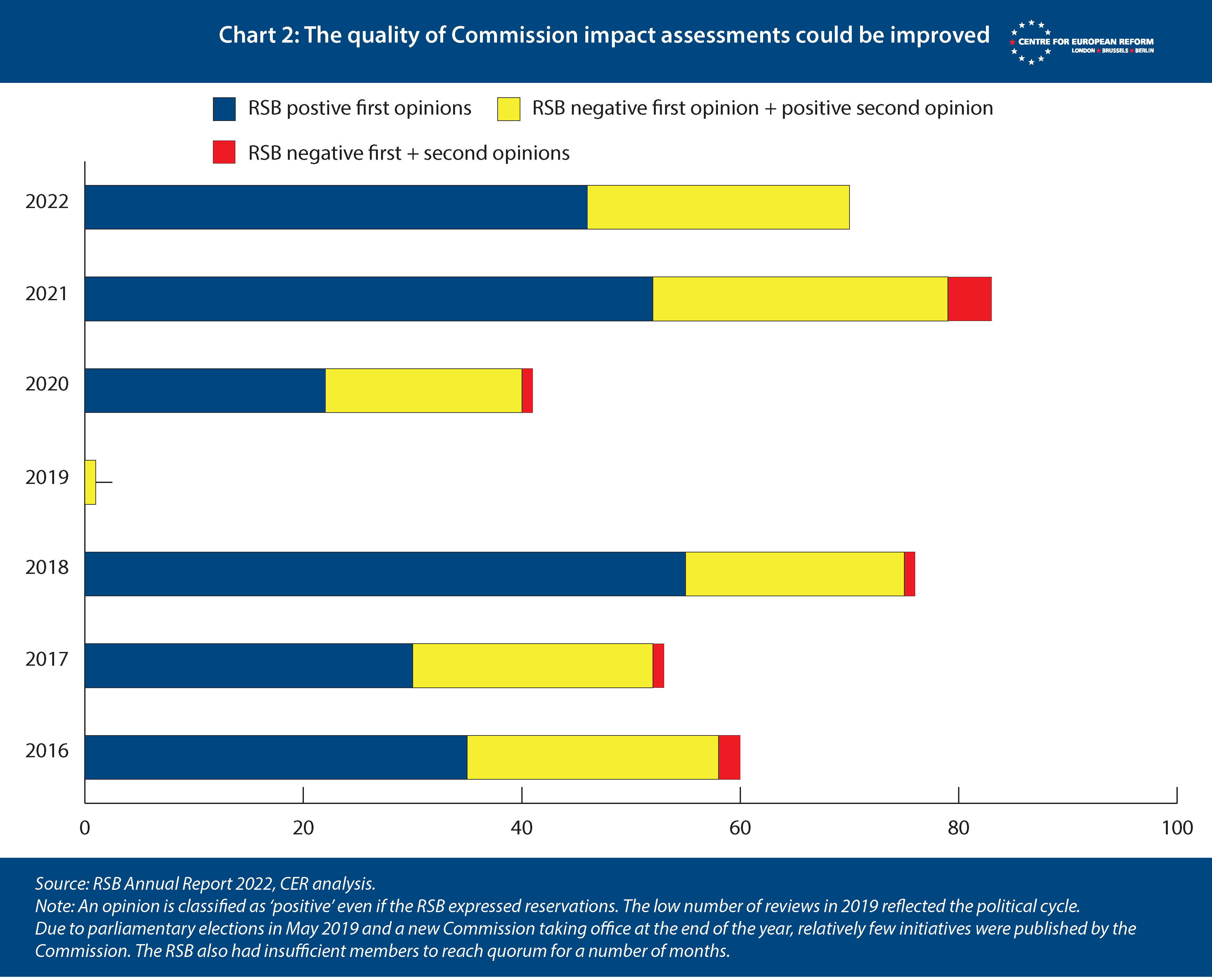

Overall, the quality of the Commission’s IAs seems to be improving – but again there is significant room for further improvement. IAs are already subject to external review by the RSB. The Board has observed an increase in the quality of the Commission’s IAs, as set out in Chart 2. However, the RSB may issue one of three opinions on Commission IAs: a positive opinion, positive with reservations, or negative. After a negative opinion, the Commission must revise and resubmit its IA to the Board. As Chart 2 shows, the proportion of Commission IAs which receives one or two negative opinions from the RSB remains high.

Two main problems explain the RSB’s critical approach to Commission IAs.

First, IAs often poorly perform their main function: identifying and analysing impacts. While the Commission is usually able to estimate the impacts of proposals on its own budgetary resources, the RSB frequently raises concerns that the Commission is not doing a good job of assessing the other impacts of its proposals – for example, on the European economy and competitiveness. As an illustration, IAs may sometimes fixate on the immediate administrative costs to business of complying with a proposal – but fail to rigorously assess how proposals might have indirect effects, such as causing European exporters to lose market share.

Second, the RSB has noted that the Commission often poorly identifies the problem a regulatory proposal tries to solve and does not do a good job of comparing policy options to address the problem. The Commission often fails to properly analyse the existing regulatory environment, or acknowledge parallel regulatory interventions or the possibility of new innovations – which can lead to a bias towards more regulatory intervention. And Commission IAs sometimes set out a range of unrealistic and extreme ‘strawman’ options, to give the impression the Commission’s preferred approach is the best option available. The RSB recently observed in relation to recent IAs that:

“the range of credible options considered was too limited, option designs were biased towards a preferred option, did not bring out clearly the available political choices or did not sufficiently anticipate combinations of options that were likely to emerge in the decision-making process”.23

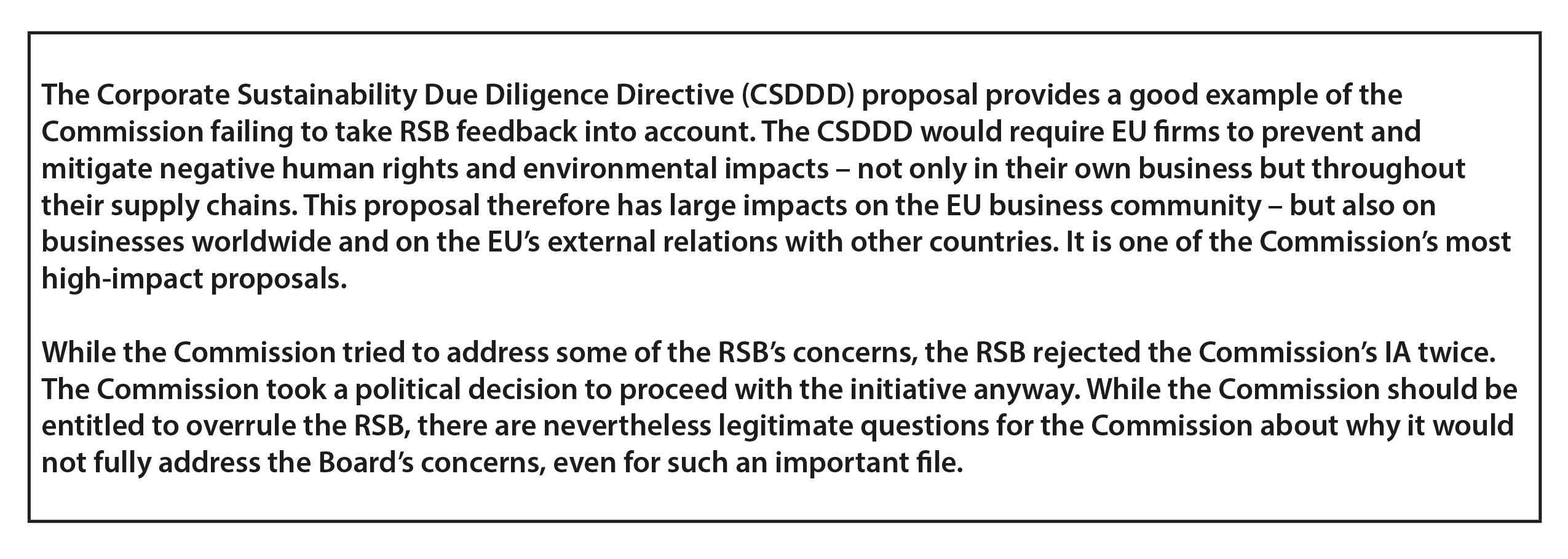

Third, the Commission often ignores the ‘reservations’ made by the RSB when it approves an IA but notes concerns about its quality – suggesting that political imperatives can too often trump the importance of careful, evidence-based analysis.24 And in important cases, the Commission has progressed proposals despite the RSB repeatedly rejecting its IAs.

In preparing impact assessments, political imperatives can trump the importance of careful, evidence-based analysis.

In part, these problems seem inherent to the Commission’s evolution, and its attempt to rely more on democratic legitimacy rather than acting as a neutral expert body. This trend is unlikely to be reversible but several steps could help improve this situation by creating more political accountability.

First, the Commission should prepare IAs for all proposals, including for delegated and implementing acts, unless the Commission certifies that the proposal is unlikely to have any significant impact or is so urgent that an IA is impractical. Without an IA, there is little possibility for external scrutiny of why decisions have been made. As explained below, it is especially important that this principle applies to delegated acts, which are an increasingly important part of EU law. The way EU laws are implemented can impose large compliance burdens on firms. It would be disproportionate to prepare an IA for all proposals – given many delegated instruments, in particular, are purely technical and have low impacts – but the Commission’s practice to date has been far too lax.

The Commission should have to certify that a proposal is unlikely to have significant impacts. To ensure accountability about how these decisions are made, the Commission should transparently set out its provisional decision that a proposal is unlikely to have significant impacts so that stakeholders have an opportunity to demonstrate otherwise. If the Commission certifies that a proposal is too urgent, it should follow up with an IA as soon as possible after proceeding with the proposal.

Second, the Commission could publish draft IAs for public comment and input, and it should publish more ‘inception IAs’.25 Because these are less detailed, and less work has been done within the Commission when an inception IA is published compared to a full IA, there is a greater likelihood of feedback influencing the Commission’s approach at an early stage and there is likely to be more political room for the Commission to change course. This step could help combat the growing concern that IAs are a “rubber stamp” to validate pre-determined outcomes, rather than a useful tool for feedback, when the Commission is still genuinely choosing between realistic alternative policy options. To be clear, however, inception IAs are in no way a replacement for full IAs.

Second, the Commission could publish draft IAs for public comment and input, and it should publish more ‘inception IAs’.25 Because these are less detailed, and less work has been done within the Commission when an inception IA is published compared to a full IA, there is a greater likelihood of feedback influencing the Commission’s approach at an early stage and there is likely to be more political room for the Commission to change course. This step could help combat the growing concern that IAs are a “rubber stamp” to validate pre-determined outcomes, rather than a useful tool for feedback, when the Commission is still genuinely choosing between realistic alternative policy options. To be clear, however, inception IAs are in no way a replacement for full IAs.

Third, while ‘competitiveness’ has long been an element which Commission IAs were supposed to consider, the institution does not have a good track record of rigorously assessing the impacts of its proposals on European firms and the economy more broadly. A separate ‘competitiveness check’ has been long-promised and received much attention in recent years,26 and was a specific commitment of president von der Leyen. However, it has not been systematically implemented: many impact assessments in the last year either contain no separate ‘competitiveness check’ or the adequacy of the competitiveness analysis has been criticised by the RSB.27 To be most effective:

- A ‘competitiveness check’ should be focused on clearly defined outcomes which regulation can directly influence – such as whether an initiative will help or hinder employment, innovation, the dissemination of technology, and productivity growth, as suggested by the OECD.28 It should be focused on supporting business dynamism in Europe (which will help Europe improve its economic growth), rather than solely being focused on mitigating negative impacts on existing business models.

- A ‘competitiveness check’ should apply to legislative initiatives, delegated and implementing acts, and also broader work by the Commission, such as strategies and work programmes. This will help ensure that the cumulative and overlapping impacts of existing laws and new initiatives are considered, rather than looking at individual pieces of legislation in isolation.

- The ‘competitiveness check’ should not simply be a technical exercise, in which case it is likely to remain subsidiary to the Commission’s political agenda. Instead, it should include steps at the political level. For example, the next Commission could include a Commissioner who would take political responsibility for raising awareness of the impacts of proposed laws and initiatives on Europe’s growth prospects, and ensuring all parts of the Commission rigorously assess their proposals.

Fourth, while competitiveness is of fundamental importance, the Commission should be cautious about overloading IAs with too many additional compulsory but vaguely defined elements. For example, the von der Leyen Commission now includes an assessment of ‘long-term strategic foresight’ in IAs. This concept is very poorly defined. It risks allowing the Commission to justify expensive and burdensome proposals based on speculation about future trends, while giving less weight to impacts which are quantifiable. IAs which are overloaded with vague concepts risk being too influenced by political considerations rather than being neutral and evidenced-based assessments to guide the Commission’s decision-making.

The role of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board

The role of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board

Regardless of the identity or agenda of its president, the next Commission will likely still enjoy an historically high level of power and political independence. While this has benefits for the Union, it also entails costs, because the Commission will be less able to perform the role of an independent expert body. One way to address this, as the Commission has already acknowledged, is by strengthening bodies which provide independent scrutiny and accountability.

The Regulatory Scrutiny Board, which was set up in 2015, is one such body. The RSB’s role is to evaluate the quality of the Commission’s IAs (for new initiatives) and its evaluations of existing laws. After two negative opinions, the initiative can only proceed with the approval of the College of Commissioners. The RSB is a highly credible body which exerts a high degree of political accountability on the Commission: decisions to override the RSB entirely have only been made occasionally. However, as the Commission grows in power and influence, the RSB could be further strengthened to help ensure a commensurate level of scrutiny and accountability.

The RSB’s ability to carry out work is curtailed through lack of resources. It needs a larger supporting team with scientific, economic and data science expertise.

Currently, the RSB’s ability to carry out work is curtailed through lack of resources. Its annual reports continually point to RSB members having a very heavy workload. The RSB currently scrutinises all IAs – but it also has the role of scrutinising the Commission’s assessments of how regulation is functioning, and the RSB lacks the resources to scrutinise more than a small proportion of those assessments. The RSB could do much more if it had more staff. Although the number of Board members was expanded from seven to nine in 2023, the RSB would benefit from having a larger supporting team with scientific, economic and data science expertise. This would allow the RSB to review a greater proportion of the Commission’s regulatory evaluations, and to conduct all assessments with more in-depth scrutiny (for example, by examining in more detail the assumptions and modelling in IAs).

The Board has remained a strong and independent body to date, however the risks of not being fully independent of the Commission are likely to grow over time. Currently, five of the members of the RSB (including the Chair) are Commission officials, and only four are independent experts. Members of the RSB are appointed for non-renewable terms of three years. This creates a ‘rotating door’ – since most RSB members have previously had a Commission role and will return to the Commission after their tenure expires. Furthermore, the RSB is reliant on the Commission to provide its secretariat, and the Commission determines the Secretary of the RSB (who is responsible for designating the RSB’s supporting staff). This may limit the RSB’s ability to consistently provide a critical voice. For example, there is a risk that the RSB will provide reservations, rather than negative opinions, especially on politically sensitive files. A more independent body could be even more critical and avoid the perception of excess proximity.

The RSB has been criticised in recent years for hindering the Commission’s political choices and itself lacking transparency.29 These criticisms are overblown: as an expert body rather than a political one, the RSB does not and should not be able to ‘veto’ proposals. Its role is to force the Commission to stop and think again if a proposal is poorly evidenced – and to force the Commission to make a clear, accountable and transparent decision if it chooses for political reasons to overrule the RSB. However, if the RSB’s powers, influence and resources are increased, as this policy brief recommends, then it would be reasonable to consider reforms to make the RSB more predictable, transparent and accountable. One step might be to enforce stronger rules on conflicts of interest. Another step would be to ensure the Board’s engagement with stakeholders is open and transparent. Stakeholders ought to be able to inform the RSB of identified weaknesses in IAs, to help inform the Board’s own analysis. However, the process for doing so should be codified so that all stakeholders understand when and how they can communicate with the Board.

The role of the member-states

The role of the member-states

The Commission and the RSB have contributed greatly to improving EU law-making standards, even if there is room to improve. However, as the Commission has become a more political body, its role as a ‘check’ on the Parliament and the member-states in the European Council has reduced. This means that member-states and MEPs urgently need to better incorporate better regulation principles into their own practices. Leaving better regulation to the Commission is no longer an option.

The Council, in particular, plays a critical role in the law-making process. The Council is tasked with scrutinising and deciding whether to approve the Commission’s legislative proposals. Under the ordinary legislative procedure, the Council may also propose amendments to a Commission proposal – and these amendments are sometimes introduced only in informal ‘trilogue’ meetings, with little transparency. The value of the Commission’s consultations and impact assessments is undermined if member-states insist on substantial changes which are not based on evidence and whose impacts have not been properly assessed. This does not imply that member-states should not be able to make political decisions that conflict with the Commission – as a group of democratically elected leaders, that is its prerogative – but rather that Council positions should be reached transparently and by weighing up evidence. Unfortunately, few EU member-states appear to robustly and systemically consult with and consider the impact of an EU law in their own countries before it is adopted at the EU level.30

In some policy areas, the Council can also promulgate certain laws without Commission involvement. In these cases, the Council has even stronger responsibilities to uphold better regulation standards.

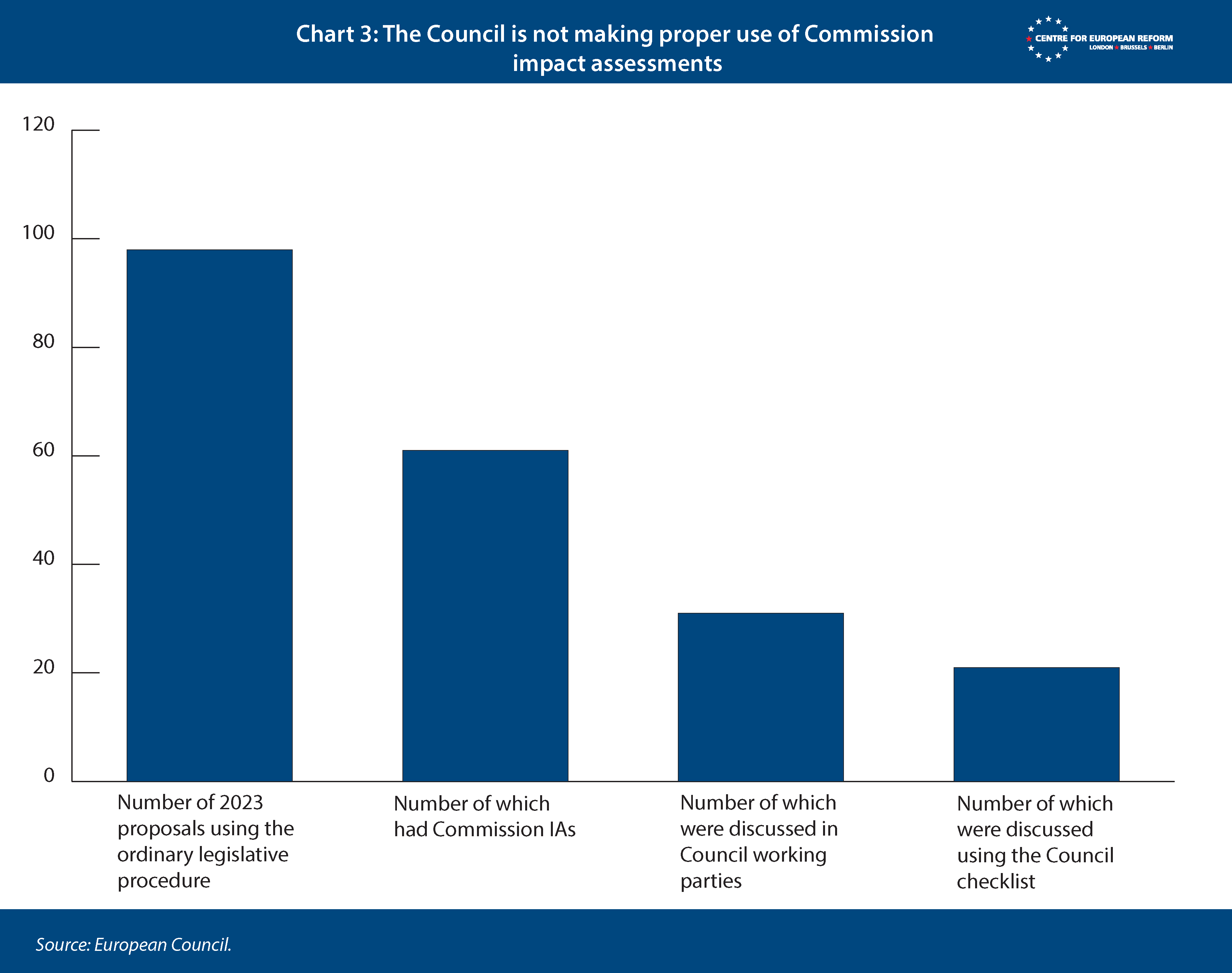

There is little evidence, however, that the Council is using the Commission’s IAs in a meaningful way to make evidence-led decisions. The Council has in place a ‘checklist’ for assessing IAs prepared by the Commission, which helps to ensure the assessments are given careful and rigorous attention by member-state representatives. Yet as Chart 3 shows, only about half of IAs were ever discussed in Council working parties. And only about two-thirds were discussed using the Council’s checklist. There is only a single case in the last 12 months where the Council requested any further analysis from the Commission in relation to a proposal.

he Council should adopt procedural steps to ensure that IAs are provided to law-makers and that the IAs are allocated time for discussion and debate in working party meetings. This would improve the likelihood that member-state representatives in the Council make evidence-based decisions.

The Council also has a disappointing record on consultation. Although member-states conduct formal and informal consultation exercises, the Council as an institution does not regularly consult in a formalised way, and ad hoc consultations within member-states can be difficult for stakeholders to identify and respond to in a timely manner. This has become more concerning because of the number of substantial new amendments and proposals that are developed at the trilogue stage, with little transparency or evidence that the impacts of these proposals have been properly assessed with stakeholders.

There are no cases at all where the Council has requested or prepared its own impact assessments.

There are no cases at all where the Council has requested or prepared its own IA for substantial amendments.31 This is disappointing given member-states promised that they would, “when they consider this to be appropriate and necessary for the legislative process, carry out IAs in relation to their substantial amendments to the Commission’s proposal”.32 In April 2017, the Council contracted with external consultants, who could prepare IAs on its behalf over the period 2018-22. But these contracts were never used and the Council could not secure renewed contracts. This suggests the Council’s capacity to produce IAs is declining.

The role of the Parliament

Parliament’s capacity to scrutinise Commission IAs, on the other hand, is far better resourced than the Council’s. The Parliament has prepared an Impact Assessment Handbook to help guide parliamentary work on IAs. The European Parliamentary Research Service also has a directorate dedicated to scrutinising IAs, evaluating existing EU law and policies, and preparing new IAs. The directorate’s Ex-Ante Impact Assessment Unit has an impressive performance in preparing ‘initial appraisals’ of Commission IAs. For example, the Unit conducted 45 initial appraisals in 202233 – a 40 per cent increase on the previous year, sufficient to ensure that virtually all Commission IAs for new legislative initiatives were appraised.34 A problem, however, is that there is very little evidence from parliamentary debates that MEPs are consistently examining Commission IAs when reviewing the Commission’s legislative proposals, or even reading the appraisals of their own research service.

Furthermore, MEPs’ amendments, even when they are substantial, are rarely subject to new IAs. Only a single parliamentary committee requested an IA in 2022.35 This suggests more work is needed to encourage MEPs to take advantage of Parliament’s capacity for research and to understand the importance of robust IAs. The Ex-Ante Impact Assessment Unit could spend fewer resources on duplicating the work of the RSB by appraising Commission IAs, and more resources on preparing IAs to reflect MEPs’ proposed substantial amendments.

While the Council and Parliament need to show more commitment to better regulation, the Commission can help. It has the right to conduct a new or supplementary IA where a proposal is significantly changed.36 The Commission should consider relying more on this power to prepare revised IAs to help map the potential impact of changes proposed by MEPs and member-states.

The role of trilogues

The role of trilogues

The current trilogue process – whereby each of the EU’s law-making institutions meets to reconcile their respective versions of legislation, ultimately resulting in an identical text agreed by all – is inconsistent with the better regulation agenda. That is especially true in light of the Commission’s determination to show political leadership – which risks the Commission being too eager to broker deals rather than to stand up for regulatory good practice. Trilogues help overcome political gridlock. However, the current process suffers numerous deficiencies:

- Trilogues take place behind closed doors with little transparency. Institutions’ progress in obtaining agreement, and changes in negotiating positions, are often revealed only through media leaks. Even the outcomes of successful full political trilogues are only summarised in press releases. Stakeholders cannot see the full text of the agreement. A final text of the law only appears weeks or months afterwards, after the completion of further ‘operational’ trilogues on matters the law-makers do not consider to be of primary political significance, legal vetting and translations.

- The principles of better regulation are often abandoned when negotiating, especially now that all three law-making institutions have more emphasis on passing laws as a sign of achievement. Positions are often updated, changed and progressed with no attempt to consult with or understand the impact on stakeholders.

- The resulting outcomes may, consequently, be coherent only as an attempt to placate different political interests, while representing the ‘worst of all worlds’ for those that have to implement and comply with a law.

The lack of transparency in the trilogue process fails to comply with the EU treaties, which require the law-making institutions to be as transparent as possible, with the Parliament and Council meeting in public, and documents about the legislative procedure being published.37 The problems with trilogues have been comprehensively outlined previously. The European Ombudsman held a strategic inquiry on the transparency of trilogues in 2015, recommending that more is needed. The 2016 IIA points to the need for “transparency of legislative procedures … including an appropriate handling of trilateral negotiations”, although little progress has been made to fix this problem. The Economic and Social Committee commissioned a study in 2017 which suggested improvements to the transparency and accountability of trilogues.38 Yet in 2018, the European Court of Justice found that the Parliament was still unlawfully refusing to publish trilogue documents.39

This paper does not assess specific changes. But there are many steps which could produce meaningful improvements – such as holding meetings in public, publishing each institution’s position, publicly documenting the outcomes of meetings, and making agendas and minutes of the meetings available.

Improving the substance, implementation and enforcement of regulation

In addition to improving the process of law-making, better regulation also implies changes to the substance of laws by making them more targeted, proportionate and clear – and ensuring they are properly implemented by member-states and enforced impartially.

“Evaluate first” and identifying alternatives to regulation

A premise of better regulation is that regulation should be a last resort where less burdensome alternatives have been carefully considered first. Unfortunately, this principle often conflicts with political reality. Law-makers see the passing of new laws as a success – after all, passing laws is their job, and achieving compromises between different EU law-makers can often feel like an achievement. Since the success of laws can often be evaluated only years later, law-makers do not always have good incentives to ensure that laws are necessary and well-designed. The less exciting process of finding ways to resolve problems without recourse to new laws, or of removing, updating or simplifying laws which are found to impose more burdens than benefits, rarely achieves public applause or attracts newspaper headlines. This creates an inherent bias towards ever more regulation. However, that trend is not inevitable, as illustrated by the Juncker Commission’s willingness to drop initiatives and to narrow down its priorities.

One tool to help address this bias is the EU’s ‘evaluate first’ principle. The Commission adopted this principle in the early 2010s40 to ensure existing regulations were evaluated before any new laws were proposed. This principle can help ensure that existing laws are being properly implemented and enforced before the Commission concludes that more laws are necessary. ‘Evaluate first’ is, of course, a technocratic instrument. However, as concerns grow that in some areas like digital regulation the current Commission has progressed initiatives faster than regulators and industry can keep up, it may become increasingly politically important for the Commission to show that any new legislation has been carefully considered.

A second tool is the use of self-regulation and co-regulation to solve problems, before more top-down forms of regulation are imposed. Self-regulation occurs where firms to decide how to deliver policy objectives, often by working together and setting industry standards. Co-regulation means that firms and regulators co-operate to decide how a law’s objectives should be achieved. In some policy areas, both approaches can often be more effective, efficient and innovation-friendly than traditional prescriptive regulation, because they give firms flexibility in delivering the desired outcome. This gives firms more ability to experiment with new technologies and to find the most cost-effective ways to achieve compliant outcomes – while leaving more prescriptive rules as a back-up plan in case industry does not deliver. Politically, the Commission ought to value self-regulation and co-regulation – they can achieve faster results and they may decrease the risk of creating unintended negative consequences for consumers, compared to more prescriptive rules.

The EU sometimes fails at its most important task for economic growth: to establish a true European single market. Only by doing so will regulation help lower barriers to doing business cross-border, improve competition, and enhance European productivity.

Firstly, many member-states have a poor record of faithfully transposing EU directives into national law. While the Commission previously initiated proceedings against those member-states, in becoming a more political body, the Commission has become less willing to take politically costly decisions when it comes to ensuring member-states implement single market rules in a timely and proper way. The number of new proceedings has been declining for several years.42 In 2022, the last year for which figures are available, the Commission opened the fewest number of cases against member-states for failure to implement EU laws than in any of the preceding four years. The Commission also closed the fewest number of cases – meaning that there is a growing backlog of instances where member-states are failing to deliver a single market.43

The Commission has tried to compensate by making more EU regulations than directives. Whereas directives need to be transposed into law by each member-state’s government, the EU’s regulations automatically apply across member-states. However, while many EU laws remain directives, particularly in crucial areas like cybersecurity which have large impacts for businesses, the Commission needs to consider ways to become a more credible enforcer.

Secondly, the Commission’s politicisation has meant it is keener to be a powerbroker, forging deals between member-states and with the Parliament. Consequently, the Commission has been too eager to grant concessions to member-states rather than insisting on rules applying in the same way across the Union. Concessions can include ‘opt-outs’ (where member-states can choose not to apply certain provisions), and allowances for ‘gold-plating’ (where EU member-states supplement EU regulations with different or tougher requirements). These allowances are sometimes necessary to get laws passed at EU level at all – and so ‘single market purity’ may not always be a realistic outcome. But the Commission, in its eagerness to prove its success at passing laws, seems to have become less conscious that member-state concessions weaken the single market and therefore have costs. They create regulatory inconsistency. They force firms to navigate different, possibly conflicting, laws across different European countries. Inconsistency benefits existing large companies that have the resources to handle this complexity, over smaller and potentially more agile and innovative firms – thereby helping dampen European business dynamism and productivity growth.

To help identify the scope of the problem, the Commission set up a database for member-states to record where they had engaged in ‘gold-plating’. However, this database has very rarely been used: member-states are reluctant to admit when they engage in ‘gold-plating’ and to subject these decisions to Commission scrutiny. The Commission should avoid allowing ‘gold-plating’ or ‘opt-outs’ in the first place. But where they are allowed, the Commission should facilitate and encourage member-states to work together to ensure transposition of EU laws occurs in as harmonised a way as possible.

Finally, a critical element of the single market is that its rules are enforced in an impartial and objective way – rather than to achieve political objectives. Despite calls for some of the Commission’s enforcement functions to have more independence, bodies like the Directorate-General for Competition have historically been robust and willing to make tough and unpopular decisions which sometimes clashed with the wishes of important EU member-states. However, in large part that has relied on political leadership rather than institutional constraints. As the Commission’s overall political stance and power grows, there is an increasing risk that enforcement functions take on a political dimension. In opening investigations against online platforms under the recent Digital Services Act, for example, many businesses perceive the Commission to have taken an approach focused on building the institution’s public profile rather than soberly assessing and applying the law. This public approach to enforcement poses real risks that the Commission will find itself politically unable to step back. The Commission may need to increasingly consider new models to improve the independence and impartiality of its enforcement functions.

Avoiding excessive use of delegated acts

Avoiding excessive use of delegated acts

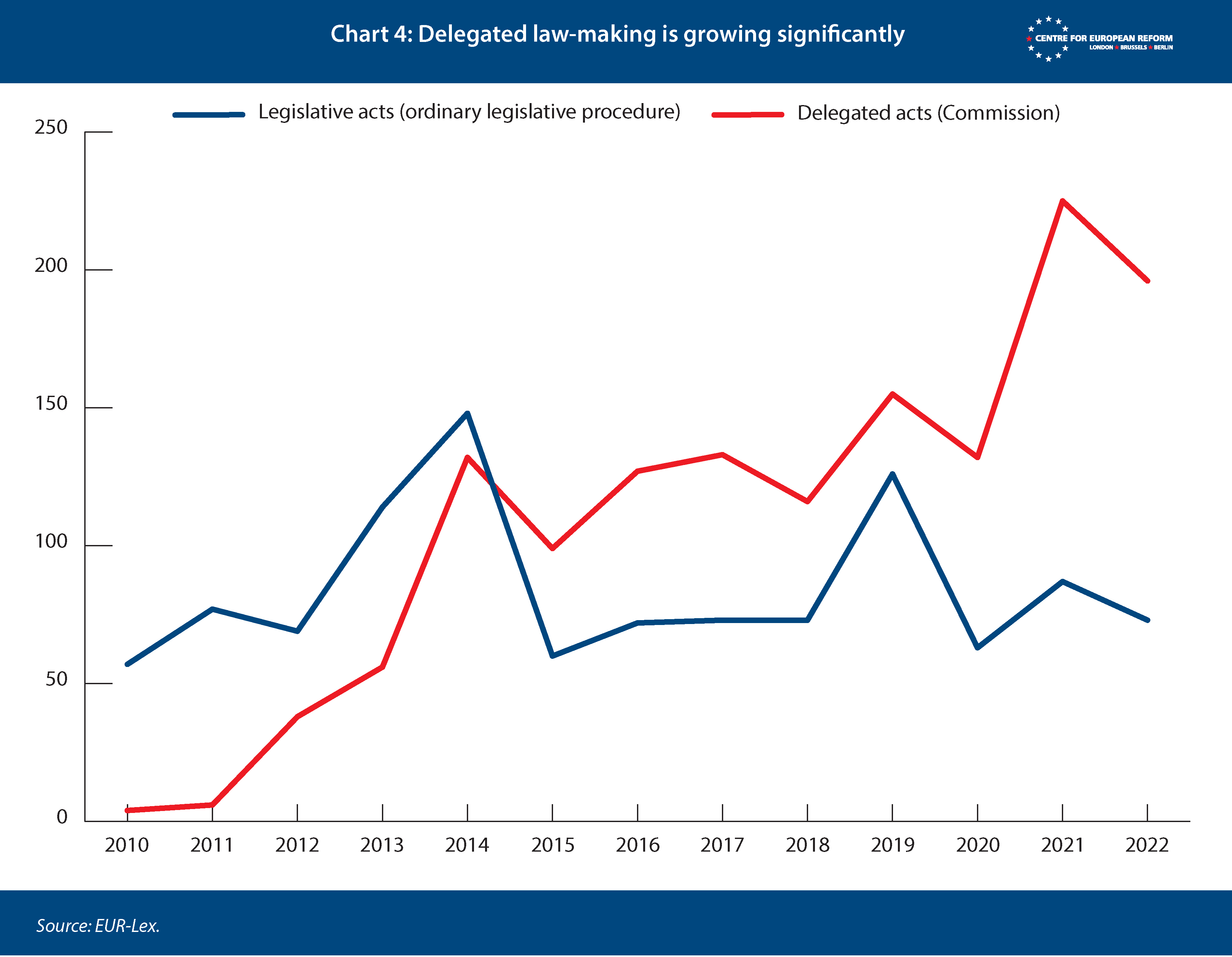

Finally, as Chart 4 shows, the Commission’s use of delegated acts has increased dramatically in recent years.

Delegated acts are increasingly used to expand the scope of laws or to introduce substantive and onerous new requirements.

In principle, delegated instruments can play an important and helpful role in the regulatory framework. They can allow primary legislation to be more outcomes-focused, principles-based, and future-proofed – while leaving the Commission with more flexibility to change specific aspects of the law. However, delegated acts increasingly pose problems:

- Once the Commission has made a delegated act, it comes into force unless the Parliament or the Council object. Delegated acts are therefore not subject to the same safeguards as primary legislation, which ordinarily require active approval of the Parliament and the Council (or implementing acts, where committees made up of member-state representatives are involved at an earlier stage, in the so-called comitology procedure). Consequently, delegated acts do not typically involve the same level of consultation and scrutiny by Parliament and the Council as other legal instruments. This lack of scrutiny is a growing problem now that the volume of delegated instruments has increased.

- As part of its shift towards being more political, the Commission has often ignored negative opinions from stakeholders and more expert bodies when making delegated acts. For example, the Commission ignored many of the recommendations of the European Banking Authority (EBA) when it imposed new rules on payments security.44 This was unexpected given the EBA had engaged closely with the banks which had to implement the new laws, and as an expert regulator felt that the Commission’s changes would create confusion and ambiguity.

- Delegated acts are increasingly used to expand the scope of laws or to introduce substantive and onerous new requirements, which is again a problem when the Commission operates in a more politicised and less technocratic way. Take the AI Act, for example, which sets out that some AI systems are ‘high-risk’ and have to comply with onerous requirements. Under its proposal, the Commission would have the power to decide that additional systems are ‘high-risk’ and therefore must become tightly regulated. Such a decision would impose significant compliance costs on businesses, potentially causing them to leave the market entirely. Furthermore, in making such a decision, the Commission only needs to consider certain factors – there are no ‘hard rules’ that the Commission is required to meet. This level of discretion risks creating large uncertainty across the European AI sector – an industry that the EU is trying to nurture.

Since the 2016 IIA, publication of delegated acts has improved, however consultation on delegated acts remains inadequate.45 The Parliament and the Council should take further steps. They should spend more time scrutinising Commission delegated acts. They should also insist on more constraints to the Commission’s powers to make delegated instruments. In particular, the EU treaties only allow delegated acts for ‘non-essential’ elements of a law. The treaties also require that the objectives, content, scope and duration are properly defined.46 EU law-makers need to pay more regard to these requirements.

Reducing regulatory burdens in existing laws

When new regulation is justified, EU law-makers should not start with the presumption that it will inevitably succeed or that it will be needed forever – and therefore that, once enacted, laws never need to be looked at again. Law-makers need to remain vigilant as to whether the cost of imposing a particular regulation continues to be needed, and remove burdens when they are no longer justified.

Some commentators argue that a focus on reducing burdens is fundamentally different to the better regulation agenda – because its goal is to constrain policy-makers’ choices,47 rather than simply to better inform them. However, the point of reviewing existing regulation is to give law-makers information about how well existing laws are delivering the expected outcomes, whether any unintended consequences have emerged, whether the benefits of the law still outweigh the costs, and whether the law is still delivering the right outcome in the most efficient way. Without these reviews, the EU lawbook will only continue to grow in length and complexity – imposing increasingly more burdens.

The EU therefore needs not only to ensure future laws are good quality – but also to periodically review the existing stock of regulation. However, overall the process of ex-post review of regulations is not as well developed or as robust as the process for preparing new initiatives. And as Chart 5 shows, the number of laws which were repealed or expired has slowed down significantly since 2020. That may have been understandable in 2021 and 2022, when the EU was rightly focused on addressing immediate crises. But it is surprising that the lowest number of laws was repealed in 2023. While this is admittedly a crude way to measure regulatory burdens, the net reduction in the number of EU laws passed using the ordinary legislative procedure in 2023 was the smallest since 2014.

The Commission’s role

The Commission has adopted numerous targets over the years to reduce burdens. Between 2005 and early 2009, the Commission said it had managed to reduce the EU’s rule-book by about 10 per cent.48 In 2007, it launched an ‘administrative burden reduction action programme’, which had by 2012 cut administrative burdens for business by 25 per cent (although this was only a gross target which ignored additional burdens imposed over the same time period). The Commission has since taken further steps. These include:

- Incorporating ex-post policy evaluations into the policy cycle. In addition to evaluations of specific laws, the Commission also conducts ‘fitness checks’ that look at how regulation in an entire sector or area is performing. Since 2015, the Commission has conducted 210 evaluations and fitness checks.

- Embedding into draft laws a requirement that the Commission conduct ex-post reviews, so it can see how a law has performed. The 2016 IIA requires the EU’s law-making bodies to consider including monitoring and evaluation clauses in all new laws.

- Including a ‘do nothing’ option in IAs – even if in practice many IAs dismiss this option out of hand. IAs also now set out a baseline for what ‘success’ looks like. That means ex-post policy evaluations have clear criteria to apply when they assess whether a regulation has achieved the intended results.

- Adopted the ‘Think Small First’ principle, which requires the Commission to give particular consideration to smaller businesses when designing proposals.

- Introducing the ‘Regulatory Fitness and Performance Program’, now rebranded as ‘Fit for Future’. This group of experts leads the Commission’s agenda on simplifying and improving legislation.

- Proposing to create a single register, the Joint Legislative Portal, to collect all the evidence used in the legislative process. This would provide an invaluable resource to help researchers and Commission staff understand the evidence underpinning a given policy initiative, which should help in evaluating its success later.

In 2018, the European Court of Auditors (ECA) assessed the Commission’s ex-post reviews. It concluded that they mostly performed better than those of EU member-states – but also highlighted that ex-post evaluation of laws risked being seen as ad hoc and not well integrated into the standard policy-making cycle.49

Given the rush of regulations in recent years – and recent declines in the number of laws being repealed – the Commission’s determination to simplify and cut regulatory burdens needs to regain momentum. Even where ex-post reviews recommended changes or deregulation, there has often been a lack of follow-through – with the Commission pushing ahead with new laws, and giving less priority to efforts to repeal or simplify existing ones. And there remains a lack of transparency about the number and status of the Commission’s ex-post evaluations. The Parliament has in part tried to fill this gap by providing its own centralised depository of review processes.

Given the rush of regulations in recent years, the Commission’s determination to simplify regulation must regain momentum.

The Commission should adopt a new initiative to more systematically identify and eliminate redundant or disproportionate regulatory burdens in existing laws. The current Commission has already announced an attempt to reduce reporting costs – and the EU has proudly announced reducing administrative costs for businesses and citizens by €7.3 billion in 202350 – but that comprises only the most obvious examples of wasteful regulatory burdens. As noted above, there are much larger costs to regulation, for example when it constrains European firms’ growth prospects. Any new initiative should target not only administrative burdens, but also substantive compliance costs.

The other potentially significant tool the Commission has adopted to cut existing regulatory burdens is the ‘one in, one out’ principle. This principle was adopted in 2019,51 but it was only integrated fully into the Commission’s working practices in 2022. The initiative tries to ensure that any new regulatory burdens are ‘offset’ by withdrawing existing burdens – with the result of cutting net administrative costs for European businesses by €7.3 billion in 2022.

The Commission should not ignore the dynamic effects of regulation: its impact on innovation, productivity, and economic growth.

The ‘one in, one out’ principle needs to be implemented flexibly: it should not, for example, prevent the Commission from proposing a law for which there is a demonstrable and compelling need. Its main role should be considered political rather than mechanistic – to raise awareness in law-makers’ minds that laws impose burdens and that the cumulative burden should not increase indefinitely over time. The Commission does not appear to have imposed the ‘one in, one out’ principle inflexibly in practice. The main problem with how the Commission has applied the principle since 2022 is that it has fixated on compensating firms for the static costs of adjusting to new regulations, and ongoing administrative costs in complying – such as the costs of reporting. This approach ignores the much larger and more dynamic effects of regulation: its impact on innovation, productivity, and economic growth. Consider, for example, cases where regulation might:

- prevent businesses taking advantage of new technologies to improve their efficiency;

- leave firms unable to take advantage of market opportunities which firms elsewhere in the world can take up; or

- discourage entrepreneurs from starting businesses in Europe – and instead either give up their ideas completely, or launch their ideas elsewhere in the world.

These types of ‘missed opportunity’ costs can immensely limit economic growth, job opportunities, and innovation in Europe. But they would not be identified at all based on the Commission’s approach to the ‘one in, one out’ rule. The Commission should explore how to make the ‘one in, one out’ principle more aligned with the type of ‘competitiveness’ assessment used in IAs. While the Commission considers how to achieve this, the ‘one in, one out’ principle can still play an important role as long as it is used flexibly and the Commission remains conscious of its limitations:

- It improves the chances that EU law-makers properly consider alternatives like self-regulation and co-regulation at an early stage – rather than assuming that the only means of “success” is new legislation.

- Where EU law-makers decide regulation is necessary, it can also help ensure they adopt the least burdensome option that still achieves the policy objectives.

- It provides good incentives for law-makers to look at whether existing EU laws are actually delivering the intended outcomes, and to repeal laws which are not performing well. Without such incentives there is a risk that laws otherwise relentlessly pile up on the statute books.

- It could encourage the growth of EU regulation where this would eliminate 27 different member-state regimes, and therefore create a level playing field across the EU and deepen the single market. The Commission has said that the replacement of 27 national regulatory regimes will be counted as an ‘out’ in applying the ‘one in, one out’ principle.

Conclusion

To meaningfully boost Europe’s economic prospects, the EU needs to ensure that established firms have as much flexibility as possible to adapt to technological and market changes, and to nurture young firms and support their growth. This requires laws which are predictable, allow firms to modernise and innovate, and do not impose excessive burdens.

Improving the quality of EU regulation is only one part of the puzzle to unlocking better productivity and more economic growth in Europe – but it is a critical one. At its best, EU regulation can set a simple EU-wide rule-book – which will give entrepreneurs the confidence to launch start-ups in Europe, give firms flexibility to innovate, help them easily expand across the EU and use Europe as a launchpad for global success. But, too often, regulation does the opposite, imposing unnecessary burdens and complexity. That can hamper firms’ ambitions for growth – or dissuade promising entrepreneurs from starting a business in Europe altogether. Better regulation should not constrain law-makers choices – but rather ensure they are equipped with the evidence, resources and tools to help understand the impacts of their proposals. Better regulation helps improve decision-making, for example by ensuring that impacts are assessed systemically, rather than allowing the loudest voices to enjoy outsized influence on law-making.

EU leaders have repeatedly committed to the right tools to help make regulation work for businesses and citizens. The Commission has taken many positive steps over the last two decades. However, the evolution of the EU institutions, and in particular the Commission, means that the need for better regulation practices is more urgent than ever. That will require a combination of technocratic steps within the Commission to help demonstrate its approach is driven by evidence, more independent accountability, and steps to protect important Commission functions from the perception of politicisation.

Commission staff are already stretched, and doing a better job at consulting, preparing IAs and reviewing the existing rule-book will impose a cost. That will require the next Commission president to insist the Commission get more funds – a tough ask when member-state budgets are already stretched – or require the Commission to do less but do it more effectively. Either step will require a change in political priorities. The urgent need to address Europe’s flailing economic growth and lack of business dynamism should serve as the basis for that political change.

The more difficult problem is how to secure genuine changes in the Council and Parliament’s practices. As the Commission has become a more political institution, the Council and Parliament cannot continue to leave better regulation practices to the Commission alone. The Council and Parliament have already agreed that they need to do more. Hopefully, both institutions’ renewed concerns about the EU’s economic performance will serve as the impetus for member-states and MEPs to deliver. Otherwise, the EU risks seeing its economic performance continue to slide down the international league tables.

Zach Meyers is assistant director at the Centre for European Reform.

March 2024

This policy brief was written thanks to generous support from Europe Unlocked. The views are those of the author alone.

View press release

Download full publication

Developing the single market

Developing the single market