An estimated 360 million eligible voters are called to elect the 720 Members of the European Parliament for the next five years.

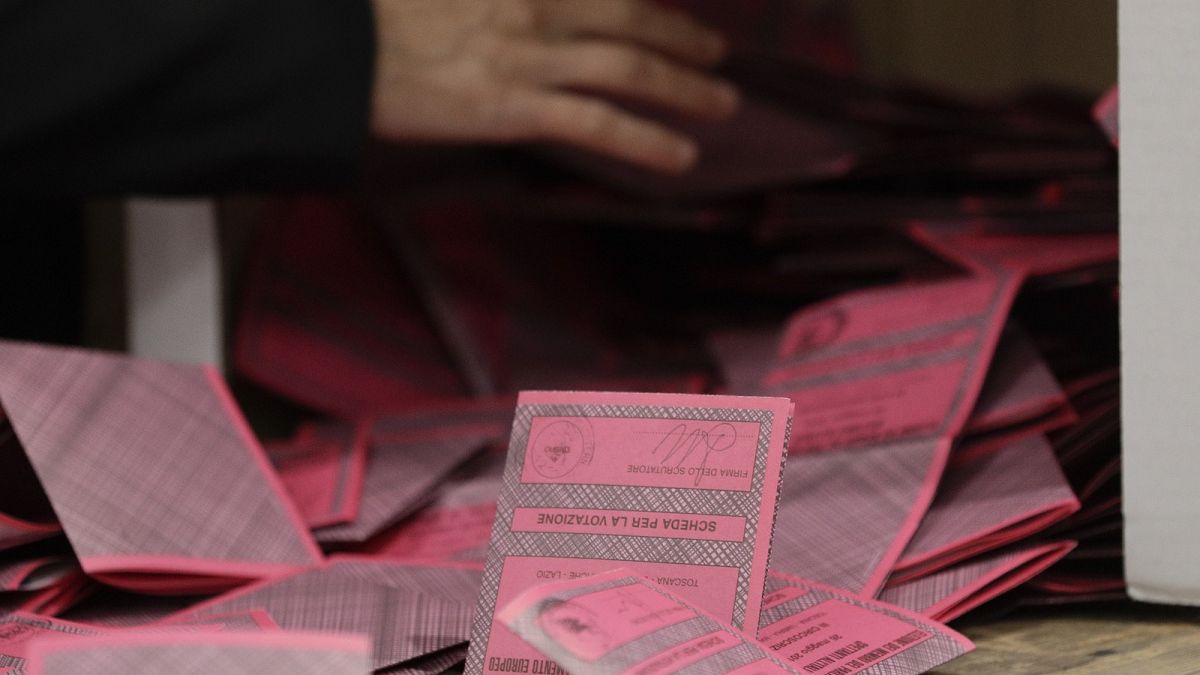

The elections to the European Parliament are kicking off on Thursday with polling stations in the Netherlands opening their doors.

Over the next three days, the other 26 member states will progressively follow suit, producing a cross-border democratic exercise that will culminate on Sunday night, when the picture of the new hemicycle is expected to emerge.

The occasion comes at a precarious, uncertain time for the bloc, which in the span of a few years has been hit with back-to-back, make-or-break crises that have profoundly reshaped its policies, defied its old-age beliefs and deepened its existential fears.

As Europeans prepare their ballots, the largest armed conflict on the continent since World War II rages on in Ukraine, a country that borders four member states and aims to one day join the ranks of the political union. This has left EU governments scrambling to find additional cash to boost their defence capabilities, a task disregarded for decades under the complacency of peacetime.

Although the possibility of a Russian attack is an increasing cause for concern, particularly on the Eastern front, where memories of Soviet occupation still resonate, Europeans are first and foremost worried about the immediate, tangible impact that this and other crises have caused on their daily lives.

High consumer prices, loss of purchasing power, rising social inequalities and stagnant economic growth are top-of-mind for voters as they head to the polls, being consistently ranked first as the issues the EU should prioritise in the next mandate.

But other hot-button topics speak directly about the EU’s role and bring its responsibility under the spotlight.

The upturn in asylum applications – about 1.14 million in 2023, a seven-year high – puts pressure on the bloc’s newly approved migration reform to yield fast results, even if the legislation will take two years to enter into force. The backlash against the Green Deal, best encapsulated in farmer protests, stands in contradiction with the worsening effects of climate change – 2023 was the hottest year on record – and the ominous reports warning the 1.5°C climate goal is irreversibly slipping away. The loss of competitiveness vis-à-vis the United States and China exposes the EU’s deficient investment flows and fuels calls for joint borrowing, business consolidation and financial overhaul.

These worries are followed by the Israel-Hamas war, which has prompted furious contestation among the European youth; the demographic changes that foreshadow an aging, shrinking labour force; continued disregard for the rule of law; the threat of foreign interference, disinformation and sabotage; and a spat of shocking assaults against politicians, including an assassination attempt on Slovakia’s prime minister.

Experts and observers have resurfaced the term “polycrisis” to define the volatile state of affairs in the 2020s. A phenomenon “where disparate crises interact such that the overall impact far exceeds the sum of each part,” as the World Economic Forum put it.

Simmering tensions

Against this bleak backdrop, about 360 million eligible voters will head to the polls to elect the 720 Members of the European Parliament, whose mandate will span five years and influence legislation meant to address the mounting challenges besetting the bloc.

It is no surprise the main narrative of this electoral cycle has been the ascendence of hard- and far-right parties, as these forces, with their radical, untested proposals, tend to prosper in times of anxiety and despair. France’s National Rally, Italy’s Brothers of Italy, the Netherlands’ Freedom Party, Belgium’s Flemish Interest and Austria’s Freedom Party are among those projected to perform well and boost their representation in Brussels.

With liberals and greens set to lose seats and socialists expected to retain their current share, the trends presage a turn to the right in the next hemicycle, which will make it difficult, or impossible, to replicate the ambitious legislative push of the past five years.

But how much influence the extreme right will wield is anyone’s guess.

The expulsion of Alternative for Germany (AfD) from the far-right Identity & Democracy (ID) group in the European parliament, prompted after its lead candidate said not all SS members were criminals, laid bare the cracks among the nationalist factions, who, despite their common views on the Green Deal and migration, are still at odds over other crucial issues such as Ukraine, Russia, NATO and China.

The AfD debacle unleashed a flurry of speculation on how hard- and far-right parties will reorganise themselves in the upcoming legislature, with all eyes on Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni as the all-mighty power broker. France’s Marine Le Pen and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán have been lobbying the premier to establish a broader group of nationalist, Eurosceptic forces, which could easily become the second largest.

Meloni’s growing influence has also spilled over into the mainstream. Ursula von der Leyen, who is vying for a second term at the top of the European Commission, has publicly courted the Italian leader to ensure her MEPs vote in the president’s favour. This overture, however, risks backfiring because it alienates the centrist parties that have until now supported von der Leyen’s agenda – and that she needs for her re-appointment.

Von der Leyen’s maneuvering might be, in fact, the real theme of this electoral cycle.

Her political family, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), has gradually moved closer to some positions of the extreme-right minority, most prominently to water down, or even bring down, environmental regulation. Progressives are incensed by this rapprochement, which they say normalises reactionary policies, dismantles the cordon sanitaire and undercuts the union’s founding pillars.

While the traditional “grand coalition” of pro-European parties is expected to preserve its ruling majority, the EPP, as the largest formation, could single-handedly derail this enduring arrangement by aligning with those to its right on a case-by-case basis. Last month, the EPP refused to signa joint declaration condemning political violence that included a commitment to never cooperate with “radical parties at any level.” Weeks later, the liberals, who endorsed the statement, were thrust in disarray after their colleagues in the Netherlands struck a power-sharing deal with the far right of Geert Wilders.

These events have inflamed tensions in the lead-up to the elections, eliciting bitter recriminations and finger-pointing between rivals. The strain is set to culminate when von der Leyen faces her (potential) confirmation hearing in September, the first political test for the new European Parliament, likely to be the rowdiest in the bloc’s history.

But before all that comes to pass, Europeans have to vote.