By Paul Kirby, BBC News, Brussels

EPA

EPAEuropeans in 20 countries go to the polls on Sunday, on the biggest and final day of voting for the European Parliament.

In a year of pivotal elections, the EU vote is especially significant, on a continent witnessing polarised politics and increased nationalism.

The run-up to the vote has been marked by violent incidents – although an attack that left Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen with minor whiplash and forced her to halt campaigning is not being seen as politically motivated.

Europe’s main centre-right grouping is expected to come top across the EU when first projections emerge later on Sunday, however three parties on the far right all have their eye on winning the most seats nationally.

France’s National Rally, Italy’s Brothers of Italy and Austria’s Freedom Party are leading in the polls, as is Belgium’s separatist and anti-immigration party, Vlaams Belang.

Voting already began on Thursday, Friday and Saturday for some EU countries – but the majority of EU member states are voting on Sunday. The European Parliament is the direct link between Europeans and the EU’s institutions.

Voting for 16-year-olds

Sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds will be able to vote for the first time in Germany and Belgium, increasing the size of Europe’s youth vote. Young Austrians and Maltese have been able to vote from 16 for some time, and Greeks can vote from 17.

In Germany alone there are an estimated 1.4 million eligible 16 and 17-year-olds among about five million first-time voters, so they could make a difference to the outcome.

The far-right Alternative For Germany (AfD) has claimed success in attracting young men especially, through campaigns on social media platforms such as TikTok.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBelgians are also voting in federal and regional elections, as well as in the European vote. Voting in Belgium is compulsory, but there was little enthusiasm among young Belgians ahead of the vote in the Flemish town of Aalst.

Vlaams Belang has won there before, although until now no other party has been willing to work with it. One young woman called Simona said young people especially were keen on their anti-immigration stance: “They like their policies on people coming here from abroad.”

Many of the town’s young voters approached by the BBC said they had not yet decided how they would vote, on a European or national level.

Dutch anti-Islam populist Geert Wilders visited Aalst on the eve of the vote to boost Vlaams Belang’s chances.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDutch voters went to the polls on Thursday and exit polls have already suggested his party is narrowly behind a left-green alliance. The result will not be known until Sunday evening.

The priorities of European voters have changed dramatically since the last vote in 2019, with Russia’s war in Ukraine and the cost of living now central in people’s minds, while migration, health and the economy are also key. Five years ago, UK voters took part in the last election before Brexit.

“We want a Europe capable of defending itself,” says Ursula von der Leyen, who has led the European Commission for the past five years and is campaigning for another term. These elections will also play a big part in deciding who runs the EU’s executive.

But voters are swayed by national issues as much as European politics, as highlighted by the Dutch exit poll, which suggested they were equally important for 48% of voters.

The biggest race on Sunday is in Germany, where 96 of the Parliament’s 720 seats at stake.

Ms von der Leyen’s conservative CDU/CSU in Germany is widely expected to win, and the biggest battle is for second place, with Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats challenged by both his coalition partner, the Greens, and opposition AfD.

Violence in run-up to vote

Several EU countries have seen violent attacks in the run-up to the vote, and in Germany politicians and campaigners alike have been targeted.

In the eastern city of Dresden, Social Democrat candidate Matthias Ecke was seriously hurt in an attack by teenagers and a Green activist was attacked, while in Berlin a former minister was hit over the head.

Interior Minister Nancy Faeser has warned of a new dimension of anti-democratic violence and said Germany’s law and constitution “must and will continue to increase the protection of democratic forces in our country”.

Robert Fico/Facebook

Robert Fico/FacebookSlovak President Robert Fico narrowly escaped with his life after he was shot while meeting supporters last month.

He has since turned his anger on his political opponents, in an apparent bid to boost support for his populist left Smer party.

Denmark’s Social Democrat Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen was knocked to the ground by a man on Friday, and although there was no apparent political motive she did have to halt campaigning.

Races to watch in France and Hungary

In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally is hoping to increase its share of the country’s 81 seats, with polls suggesting a big lead over President Emmanuel Macron’s Renew party and the resurgent Socialists under Raphaël Glucksmann.

The big draw for National Rally has been its 28-year-old leader, Jordan Bardella, who has led the European campaign.

So seriously has the government taken Mr Bardella that Prime Minister Gabriel Attal joined him in a one-on-one debate, attacking his party’s close relationship with the Kremlin.

Mr Macron’s party list for this election is led by Valérie Hayer, a little-known politician in comparison with Jordan Bardella.

Meanwhile, in Hungary, Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party is facing one of the biggest challenges to his rule so far from Peter Magyar and his new centre-right Tisza party.

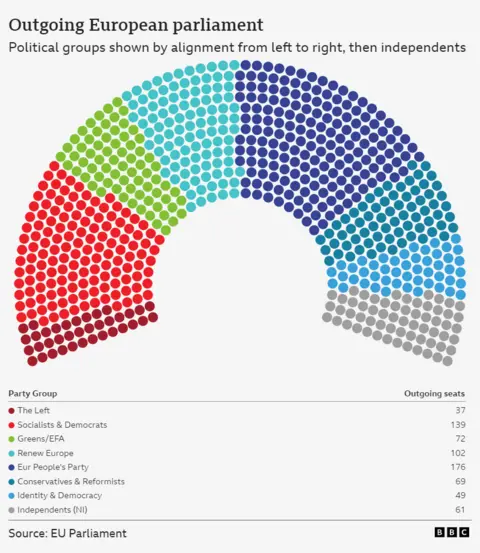

For all the big national races, the real power in the European Parliament is wielded by political groupings from different member states, and it is the centre-right European People’s Party made up of conservative parties across the EU that is widely tipped to remain the biggest political force in the 720-seat chamber.

The centre left has few parties in power in Europe, but is still expected to come second.

It is the two right-wing groups, home to several far-right parties, that are expected to increase their support.

Giorgia Meloni’s party Brothers of Italy sits in the European Conservatives and Reformists along with Spain’s Vox and the Sweden Democrats, while France’s National Rally is part of Identity & Democracy, as well as Italy’s League and Austria’s Freedom Party.

That leaves open the question whether they are prepared to work together, or if they might find common ground with the centre right.

The big losers in this contest could be the centrists, who include France’s Renew, and the Greens. As one Green campaigner in Brussels said on the eve of the vote: “Everything has moved to the right.”.