The European Commission warned in September 2022 that

“the next winters – not just this one – will be

difficult, make no mistake about that”.1 In this

article, Joe Perkins 2 and Clemence Rainaut review the

various interventions governments made to support households and

businesses. Future energy support schemes should better meet the

twin objectives of providing support for essential use,

particularly by vulnerable groups, and maintaining effective

signals for reducing demand over time.

Introduction

In the short term, prices play two central roles in the

operation of a market:3

- First, they affect the distribution of surplus between the

sellers of a good and its consumers. Other things equal, when

prices rise, suppliers receive more of the surplus, and consumers

less. - Second, they help to balance supply and demand within a market.

Higher prices tend to increase supply and reduce demand, while

lower prices have the opposite impact.

If the first role of prices has been central to recent

discussions of energy market dynamics in Europe, the second role of

prices, in balancing supply and demand in a market, has been

largely overlooked. We discuss in this article how this could make

interventions significantly less effective, or much more expensive,

than would otherwise be the case.

Responding to high energy prices

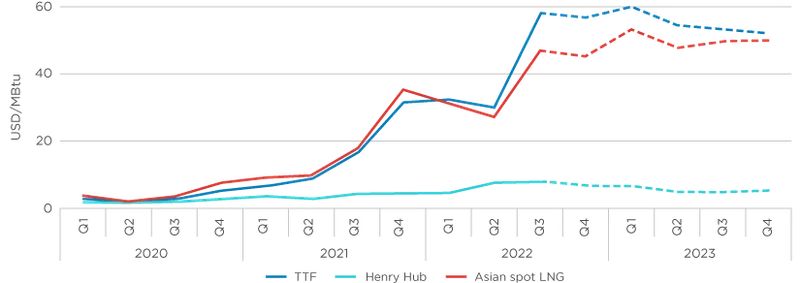

There has been an unprecedented increase in energy prices since

2020. Most European countries rely heavily on gas, which is the

primary driver of the recent power price increase. This is because

gas-fired power stations are typically the marginal generators of

electricity, so their production costs drive power prices. In

Europe, third-quarter 2022 Dutch gas prices (TTF) were more than

eight times their five-year average. Asian spot liquefied natural

gas (LNG) prices rose in Q3 2022 to their highest quarterly level

on record (Figure 1). In Europe and Asia, forward curves as of the

end of September 2022 expected prices to remain at high levels in

2023.

Figure 1: Main spot and forward natural gas prices,

2020-2023

Source: IEA, Gas Market Report, Q-4 2022

In these circumstances, governments across Europe have

intervened to reduce the impact of energy price rises on households

and businesses. Higher energy prices can have dramatic effects on

consumers’ disposable incomes and well-being. Moreover, poorer

households tend to spend a greater proportion of their incomes on

energy than richer ones, making impacts on the poorest groups

particularly severe. Governments’ concerns have also grown

about small businesses and about inflation, which has exceeded 10%

for the first time in decades in several European

countries.4

While there has been some moderation in prices recently, the

supply disruption following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is

likely to last. The European Commission warned in September 2022

that “the next winters – not just this one – will

be difficult, make no mistake about that”.5

It is therefore important to review the various interventions

governments have made to support households and businesses. Their

efficacy varies. As do their secondary effects, including on the

price of energy and the costs faced by government. There are likely

to be ongoing challenges in coming winters to ensure that support

schemes are well prepared to cover core consumption, especially for

vulnerable consumers, while allowing price mechanisms to help

balance supply and demand.

The effects of a supply reduction

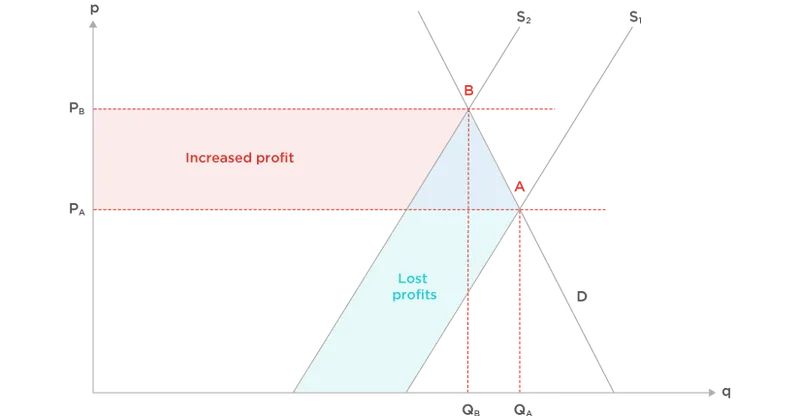

It is helpful first to consider the effects of a negative shock

to energy supply on prices and profits, without intervention.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between prices and quantities

in an energy market. The curve S1 shows the supply curve

before a shock; this aggregates the short-term marginal costs of

energy suppliers. The curve S2 represents the supply

curve after a negative shock, such as a cut-off in Russian supplies

of gas. For any given price of energy, there is less supply

available. The curve D represents the demand of energy

consumers.

Figure 2: The effects of a supply reduction

Both supply curves are upward sloping – production

increases as prices increase – while the demand curve is

downward sloping, because consumers reduce their demand at higher

prices. However, demand and supply curves are quite steeply sloped.

This is due to the expectation that energy supply and demand are

relatively inelastic in the short term. Energy producers cannot

quickly increase their production levels, while many energy

consumers cannot reduce their demand without significant

hardship.6

The supply shock moves market equilibrium from point A to point

B. Quantities sold fall from QA to QB, while

prices rise from PA to PB. If we assume that

firms were making normal profit levels before the supply shock, the

red shaded area illustrates the increase in profits (what we might

call “windfall” profits 7) due to the supply

shock, and the green area shows lost profits. Consumer surplus,

meanwhile, has fallen by the sum of the red and blue shaded

areas.

This diagram illustrates how a supply shock can have dramatic

impacts on market outcomes, with prices and profits moving

particularly significantly when supply and demand curves are

steeply sloped.8 In general, this price mechanism has a

beneficial effect – it ensures that those consumers with the

lowest willingness to pay are the first to reduce their demand, and

those producers with the lowest cost of producing more are the

first to increase their supply. This means that the response to the

supply shock is efficient, in the sense that, given prevailing

market conditions, no one could benefit without someone else losing

out.

We would expect some of this reduction in demand to come about

due to changed behaviour by consumers who gain little value from

one extra unit of energy. For instance, they might become more

diligent in switching lights off in empty rooms, or switching the

heating off when they go out. Governments aim to encourage such

behaviour change to ease pressure on supply and prices.

However, the essential nature of energy to household well-being,

and the scale of recent price rises, means that some consumers may

be forced into cutting their consumption because they are unable to

afford their basic energy needs. There can then be very significant

hardship for those who reduce their consumption, or those who have

to pay much more than expected. Indeed, in the UK, the NHS

Confederation warned in August 2022 that there could be a public

health emergency due to higher energy prices in the absence of

intervention.9

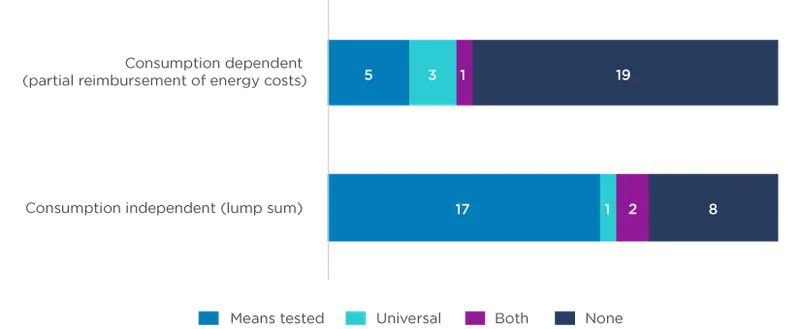

This makes it understandable that policymakers would want to

intervene in the market to alter outcomes, supporting consumers to

pay their energy bills. European countries have implemented four

main categories of direct support measures. As Figure 3

illustrates, these are: lump sum cash transfers, either universally

awarded or targeted at specific groups of consumers; and subsidies

of energy bills, either universal or targeted. Each has different

pros and cons, which we discuss in turn.

Figure 3: Overview of direct support instruments

targeting households introduced in EU27+UK in 2022

Source: Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the energy

crisis, 21 October 2022, accessed at Bruegel.

Cash transfers (lump sum payments)

The initial response of many European countries to the energy

price rises was to provide cash transfers to households, whether

targeted at more vulnerable households, or available to

everyone.10 For instance, in February 2022, the UK

government announced a package of measures that promised most

households payments of £350 to help pay their energy and

housing tax bills.11 Similarly, in March 2022, the

German government agreed an expanded set of measures to help with

energy prices, including one-off tax relief payments of €300,

and an extra €100 for families on social

benefits.12

Cash transfers have many advantages – they can be targeted

at vulnerable households, typically have low administrative burdens

and are quick to implement. They do not distort the operation of

the energy market, meaning that they maintain incentives on

households to reduce demand in response to high prices.

However, this can also be seen as the major downside of cash

transfers. Because they are not linked to consumption, they do not

reflect how high prices affect households in practice. A household

in a well-insulated modern apartment in a warm part of the country

might receive the same cash transfer as one in a poorly-insulated

old house that is frequently exposed to very cold weather. The

sense that the scale of earlier measures was insufficient to

respond to the needs of some households has been an important

driver of governments’ willingness in recent months to

implement measures that subsidise energy costs directly.

Universal subsidies linked to energy consumption

Another option can be a universal subsidy linked to energy

consumption for all households and businesses.

In Europe, partial reimbursement of energy costs has been

implemented in Cyprus, Greece, Portugal and Sweden.13 A

price cap, setting the maximum amount that suppliers are permitted

to charge per unit of energy consumed, has been introduced or

modified in 2022 in Austria, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania,

Montenegro, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Slovakia and the United

Kingdom.14 For instance, in the United Kingdom, the

pre-existing price cap for gas and electricity rose to an

annualised level of £4,279 in January 2023, but bill-payers

were protected from much of this rise under the government’s

Energy Price Guarantee, which limited the annualised bill for a

house with typical consumption to £2,500 – from April,

the Energy Price Guarantee will increase to

£3,000.15 Suppliers are typically reimbursed, in

whole or in part, for the difference between the costs they incur

and the amount they can charge consumers. Similarly, Bulgaria,

France and Luxembourg have implemented freezes of the regulated

price, or limited increases below what might have been

expected.16 For instance, in France in 2021, the Prime

Minister promised to limit the increase in regulated tariffs to 4%

for the whole of 2022.17 For 2023, regulated tariffs can

increase by up to 15%.18

This universal subsidy approach eases the affordability problem

for consumers, but can be very expensive. The International

Monetary Fund estimates that untargeted distortionary measures,

largely universal subsidies, will on average cost European

countries around 0.8% of GDP in 2022/23, more than half of the

total fiscal cost of energy support measures.19

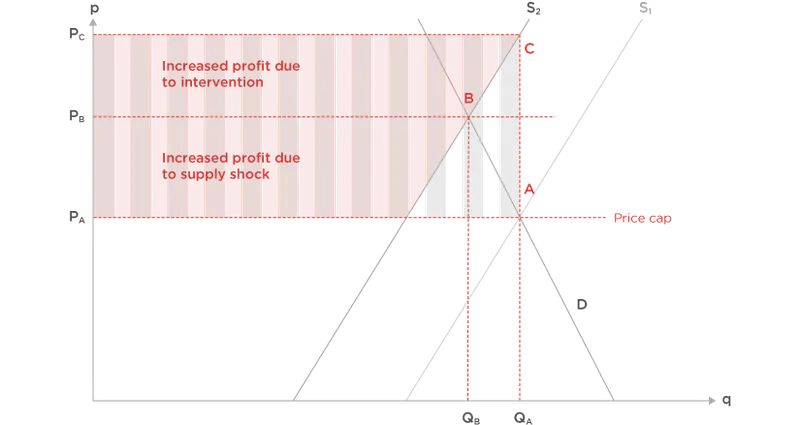

Figure 4: Impact of universal subsidies

At an appropriate scale, a universal subsidy scheme can

dramatically improve affordability for consumers, and reduce the

risks of serious hardship. But it is a blunt tool, which can

introduce several other risks.

The subsidy measure increases the cost of the intervention

because it blunts the incentives to reduce demand. To an extent,

that is intended, in order to reduce hardship, but the universal

scope of the subsidy also reduces incentives to cut back on the

proportion of energy consumption that consumers would have been

willing and able to give up if they had faced higher prices.

As a result, the price that the government pays for energy will

be even higher than market prices in the absence of intervention,

as is illustrated in Figure 4. At the capped price of

PA, consumers wish to consume QA units of

energy – the same as they were consuming before the supply

shock. But higher prices are required to bring forward this amount

of energy. The market price rises to PC, which is the

corresponding price for QA on the new supply curve

S2. Energy providers thus receive even higher profits,

and the government pays the difference between PA and

PC (grey shaded area).

In principle, “windfall” taxation of energy company

profitability could limit the scale of this impact, and reduce the

fiscal costs governments face. The European Council agreed levies

on energy company profitability in September 2022, 20

and taxes on windfall profits have been implemented or extended in

several European countries during 2022: the Netherlands in

September, Romania in October, Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the

United Kingdom and Czechia in November, and Germany and Portugal in

December.21 Well-designed windfall taxes could transfer

some of the surplus resulting from the energy supply shock away

from firms and towards consumers or taxpayers. It is, though,

important to ensure that the implementation of windfall taxes does

not further reduce energy supply, and that any impacts on long-term

energy investment are minimised.

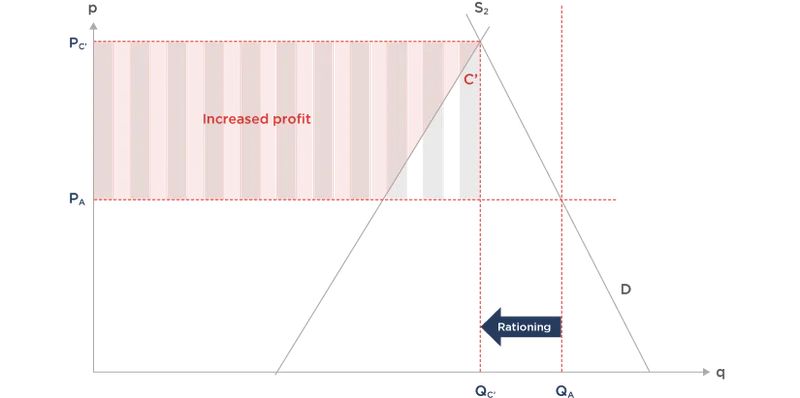

Moreover, universal subsidies can increase the risk that

administrative rationing will be needed to mitigate the pressure on

supply, for instance in the event of higher than expected demand

due to a particularly cold winter, or a further constraint in

supply. This can be seen in Figure 5, where at the capped price

PA, consumers demand QA, which, due to an

additional shock, supply can no longer meet at any reasonable

price. In this case, administrative rationing is required to ensure

demand falls to a level that can be supplied

(Qc).22

Figure 5: Risk of rationing of supply

The possibility of rationing has been discussed in several

European countries, though fortunately no significant

administrative rationing has been needed so far.23 If

required, such administrative rationing can have significant

negative consequences, since it is very difficult to estimate which

energy uses are of highest value without price signals. Rationing

can also encourage rent-seeking behaviour, whereby firms try to

gain privileged access to the rationed supply.24

Targeted subsidies linked to energy consumption

An alternative approach to mitigate the effects of the supply

shock is to subsidise the prices paid by some groups of consumers.

The targeted group of consumers can take various forms: for

instance, it could be households rather than businesses, or those

households or businesses assessed as vulnerable.

In Europe, means-tested partial reimbursement of energy costs

for households has been implemented in Belgium, Greece, Italy,

Lithuania, Romania and Spain.25 In October 2022, the

Spanish government announced the creation of a

“temporary” new category of electricity consumers (1.5

million households) entitled to a 40% discount on their bills. For

businesses, the Irish government will provide eligible businesses

with compensation of 40% of the increase in their energy bills (gas

and electricity), capped at €10,000 a month.26 In

France, support for small and medium-sized enterprises, initially

covering 25% of their consumption, was announced in October

2022.27

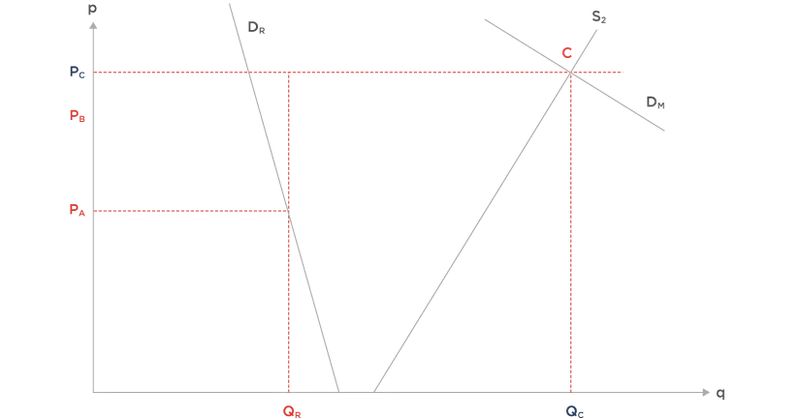

We can extend the setting above to consider the expected impacts

of such subsidies on market outcomes, as illustrated in Figure 6.

In this diagram, the price PB and the supply curve

S2 are the same as in Figure 2 – they show energy

supply following a cut-off in Russian gas supplies, and the price

that would be charged without intervention. But demand is split

between two groups, R (regulated prices) and M (market prices) (we

can think of these as domestic and business consumers, or

vulnerable groups and other consumers), with demand curves

DR and DM. We assume that the demand curve is

more steeply sloped for group R, reflecting for instance the

expectation that domestic demand is more inelastic in the short

term than business demand.

Figure 6: Targeted subsidies for domestic

consumers

The left-hand part of the figure shows outcomes for consumers

with regulated prices, which we assume to be capped at

PA, the price before the supply shock. They consume

quantity QR at this price, more than they would have

done at PB. As a consequence, prices increase for

everyone else, to a level higher than they would have faced without

intervention. In the right-hand part of the figure, the curve

DM shows demand from consumers exposed to market prices.

Market prices are not capped, so prices are determined by the

intersection between the demand and supply curves, at point C.

Overall market prices are PC, while the total quantity

of energy consumed is QC. Note that PC is

higher than PB (and QC is greater than

QB). This is because consumers facing regulated prices

have no incentive to reduce their demand. Instead, all demand

reduction comes about through the group of consumers exposed to

market prices, and higher prices are therefore required to achieve

the same level of demand reduction. The untargeted group faces the

burden both of higher prices and of energy-saving efforts.

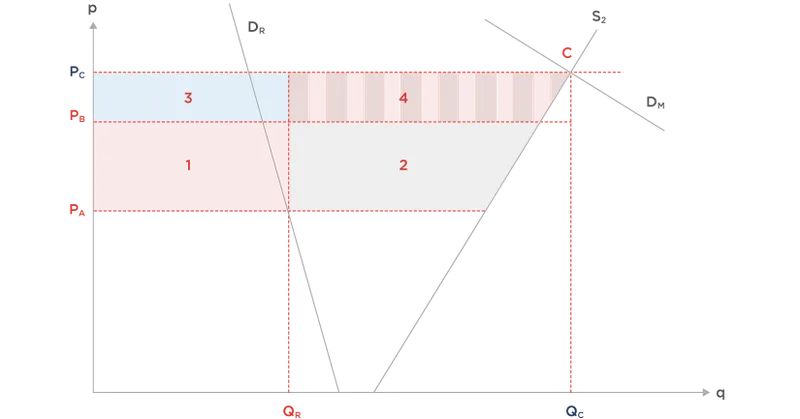

Figure 7 displays the welfare consequences of this intervention.

As a result of the supply shock, suppliers’ profits increase by

the sum of areas 1, 2, 3 and 4. Areas 1 and 2 are the same as the

red shaded area in Figure 2 (as the price increased from

PA to PB). However, area 1 is now paid for by

the fiscal authority, rather than by consumers. Areas 3 and 4

represent additional profits for firms, due to the increase in

prices following the subsidies. Area 3 is paid for by the fiscal

authority, while area 4 is paid for by consumers exposed to market

prices.

Figure 7: Welfare consequences of targeted

subsidies

Therefore, relative to the situation without intervention,

supplier profits are higher and consumers with regulated prices are

better off, while the fiscal authority and consumers exposed to

market prices are worse off. In addition, unlike in Figure 2, we

observe some inefficiency – there are consumers with

regulated prices who would be prepared to sell some of their energy

to unprotected consumers at prevailing market prices.

These effects will be larger when the group of subsidised

consumers is greater and when the demand of the subsidised

consumers is more elastic (as this means more of the burden of

adjustment will be borne by unprotected consumers).

The best of both worlds: core consumption subsidies?

The effects explained in Section 5 bring further insights for

considering another type of targeted subsidy, in which support is

targeted like a progressive income tax schedule. Consumers can buy

a given amount of energy at a low price, then a further block at a

higher price, and then consumption is exposed to market prices. The

objective of this approach is to ensure that consumers are able to

cover their essential needs, such as core heating, but there are

strong incentives to reduce consumption at the margin. In

principle, this could mean that there is little or no

price-increasing effect of the subsidy, because consumer demand is

not increased. Risks of administrative rationing should also be

greatly reduced because consumers are still exposed to market

prices. Moreover, even though the subsidy can be applied to all

consumers, it is less costly than the universal subsidy discussed

in Section 4 as it applies to only a proportion of energy

consumption.

Approaches of this kind have been adopted by some European

governments. For instance, both Austria and the Netherlands have

introduced price caps on the first 2900 kWh of a household’s

electricity consumption. In Croatia, there is a low price cap on

consumption up to 2500 kWh, followed by a higher cap on additional

consumption. Schools, kindergartens, universities, old people’s

homes, NGOs, and administrative buildings pay a fixed price. Greece

has implemented a subsidy along with household-specific incentives

to reduce demand; consumers who cut their average daily consumption

by 15% year on year receive a 50 euro subsidy per MWh

consumed.28

Such policies hold out the hope of an appealing mix of

government support for energy consumption that is really needed,

good incentives on consumers to reduce demand in response to the

supply shock, and relatively limited fiscal costs. However, it is

always difficult to ensure that subsidies of this kind are targeted

at those consumers that need them. For instance, larger households

will typically have higher intrinsic energy needs, as will those in

cold areas or poorly insulated houses – often private renters

who have limited control over their energy efficiency. Moreover,

longer term these policies could create risks of gaming by

consumers, such as by dividing up households artificially to

benefit from consumption subsidies.

The trade-offs involved in subsidising energy consumption can be

seen in Figure 8, created by the World Bank economist Nithin

Umapathi. In this framework, the ideal approach would follow the

red line, with high levels of assistance for the poorest groups,

gradually tapering off as income increases. But in practice,

governments face a trade-off between targeting assistance narrowly,

as in the orange box, which could miss out lower to middle-income

households, or providing broad-based support, which may be

insufficient for the poorest groups. It should be noted, however,

that while this framework is complicated enough in itself,

governments will typically care about multiple dimensions of energy

need, including for instance age and health status as well as

income.

Figure 8: No subsidy scheme is likely to target

consumers optimally

Source: Brookings, How to help people in Europe and Central Asia

pay their energy bills, October 2022

Preparing for next winter and beyond

Overall, the scale and nature of European governments’

subsidies to energy demand can be seen as a reasonable reaction to

a crisis situation that posed a serious threat to living conditions

and well-being across the continent. However, as this article has

shown, they have not come without costs. Subsidies have reduced the

incentives on consumers to cut their demand, meaning that prices

have risen still further and that the risks of administrative

rationing have increased. Subsidies have boosted the already

elevated profits of energy companies, at least in the absence of

windfall taxation. The fiscal costs are also non-trivial; in

November 2022, Bruegel estimated that Germany had committed 7.4% of

its GDP to energy support measures, more than €260

billion.29

Beyond the issues covered here, there are also some wider

economic risks of the interventions we have seen. This article has

examined outcomes in a single energy market with a single

government deciding whether to introduce subsidies. In reality,

international energy markets are closely interlinked, particularly

within Europe. This means that energy subsidies could have a

snowball effect across markets. Subsidies in one country tend to

increase prices both in that country and in neighbouring markets

– potentially increasing the pressure for subsidies in

neighbouring countries too. Moreover, because gas is priced in

dollars, subsidy schemes in practice involve governments taking on

substantial liabilities denominated in a foreign currency, with

potential risks for perceived fiscal sustainability.

While energy prices have fallen somewhat recently, there is

unlikely to be a quick fix to the problems faced by European

countries. This means that policymakers should consider how future

energy support schemes can be designed more smartly, with the twin

objectives of providing support for essential use, particularly by

vulnerable groups, and maintaining effective signals for reducing

demand over time, through prices and other methods. This may

include moving back to lump sum transfers that are not linked to

energy consumption, or concentrating subsidies on core consumption

only.

In the long run, the crisis has further suggested that the

energy trilemma – the apparent trade-off between

affordability, energy security, and decarbonisation – is no

more. One of the tragic ironies of the current situation is that

some environmental policies that countries postponed because they

were too expensive, such as energy efficiency measures, might have

easily paid for themselves in recent years.30 The

striking progress in reducing the costs of low-carbon generation

such as wind and solar creates great opportunities for improving

all three arms of the trilemma over time, with more affordable

green energy that is less subject to global geopolitical

developments.

Footnotes

1 European Commission, Opening remarks by Executive

Vice-President Timmermans and Commissioner Simson at the press

conference on an emergency intervention to address high energy

prices, September 2022, accessed at European Commission.

2 Joe Perkins is a Senior Vice President and the Head of

Research at Compass Lexecon. Clemence Rainaut is an Analyst at

Compass Lexecon. The views expressed in this article are the views

of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of

Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates,

its employees or its clients.

3 Longer term, prices also affect incentives to invest in

producing a good, and they influence the allocation of resources

across different markets.

4 See Eurostat, “Annual inflation up to 10.6% in the

euro area, European Commission”. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/15265521/2-17112022-AP-EN.pdf/b6953137-786e-ed9c-5ee2-6812c0f8f07f.

Accessed 3 February 2023.

5 European Commission, Opening remarks by Executive

Vice-President Timmermans and Commissioner Simson at the press

conference on an emergency intervention to address high energy

prices, September 2022, accessed at European Commission.

6 Typical estimates of price elasticity of demand

consumers are around -0.1. That is, demand falls by around 1% for

every 10% increase in prices. See, for instance, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/532539/Annex_D_Gas_price_elasticities.pdf.

7 This green area can be taken to represent the lost

profits of those suppliers who are no longer in the market after

the supply shock – for instance, Russian gas

suppliers.

8 If demand and supply were more elastic, quantities

would change more, but prices and profits would change

less.

9 NHS Confederation, Could the energy crisis cause a

public health emergency? 2022, accessed at NHS.

10 We term as “cash transfers” measures that

provide money to households that is not linked to the level of

their energy consumption. In practice, these measures provide money

in various ways, particularly through the tax or benefit

systems.

11 See https://www.gov.uk/government/news/millions-to-receive-350-boost-to-help-with-rising-energy-costs.

12 See https://www.dw.com/en/germany-unveils-measures-to-tackle-high-energy-prices/a-61243572.

13 Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 21 October 2022. Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/national-policies-shield-consumers-rising-energy-prices.

14 Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 21 October 2022, Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/national-policies-shield-consumers-rising-energy-prices.

15 See https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/publications/latest-energy-price-cap-announced-ofgem.

The Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) reduces the unit cost of

electricity and gas that consumers pay. The EPG will increase so

that the bill for a consumer with typical consumption paying by

direct debit will be £3,000 (expressed in annualised terms),

compared with £2,500 – which was the maximum level up

to 31 Match 2023. In addition, there are cost-of-living payments of

£900 for those on means tested benefits, £300 to

pensioners, £150 to those on disability benefits and doubling

support for those on LPG or heating oil.

16 Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 21 October 2022, Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/national-policies-shield-consumers-rising-energy-prices.

19 See https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/12/helping-europe-households-Celasun-Iakova.

20 See https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-63089222.

21 Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 29 October 2022, accessed at Bruegel.

22 Alternative energy saving approaches can help to

mitigate the effects of subsidies on increasing demand. For

instance, in September 2022 Germany implemented measures including

a ban on retail stores keeping their doors open and limitations on

the heating of public buildings, with the hope that they would

reduce gas consumption by around 2%. See https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-energy-saving-rules-come-into-force/a-62996041.

23 See https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/germany-might-consider-gas-rationing-uniper-ceo-2022-09-05/.

24 Bulow and Klemperer, Regulated prices, rent-seeking,

and consumer surplus, 2012, accessed at Bulow and Klemperer.

25 Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 21 October 2022, accessed at Bruegel.

26 Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 21 October 2022, accessed at Bruegel.

27 See https://www.economie.gouv.fr/hausse-prix-energie-renforcement-dispositifs-aides-entreprises.

28 See Bruegel, National fiscal policy responses to the

energy crisis, 21 October 2022, accessed at Bruegel, and https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/699535/IPOL_STU(2022)699535_EN.pdf.

29 See https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/national-policies-shield-consumers-rising-energy-prices.

30 See, e.g., https://www.newstatesman.com/environment/2022/03/why-cant-the-uk-manage-to-insulate-its-homes.

Originally published 22 February 2023

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.