The Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) proposal in 2023 can be a first step. The EU must take a ‘single market’ perspective to develop a complete green industrial policy. To achieve a globally competitive, cleantech powerhouse, Europe cannot rely on fragmented national measures since those will not steer private investments in clean technology at the scale and speed that is needed. Instead, the EU could replicate the US by establishing an institution similar to the US Advanced Research Projects Agency with the mandate of fostering high-risk, early-stage development projects for new clean technologies.

The new political landscape around the European Green Deal

The European Green Deal (EGD) set clear and ambitious climate targets for 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050. It unleashed a wave of legislation strengthening traditional EU climate, energy and environmental policy instruments alongside brand-new policy instruments. The latter includes: the Just Transition Fund; a new, separate emission trading system (ETS 2) covering buildings and road transport; the Social Climate Fund; and the world-first Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

Ahead of the 2024 European Parliament elections, a number of voices are calling to slow down the transition process, driven by fears (often misplaced) of trade-offs between decarbonisation and economic competitiveness[1]. It is in this less auspicious political climate that the next European Commission will have to ensure that the green roadmap, tabled by von der Leyen’s Commission, is implemented.

Finding a new way to keep political momentum high for the green agenda, and ensuring that existing targets and instruments are implemented, will not be trivial. Perhaps shining a spotlight on the macroeconomic dimension of the green transition could help. Europe’s industrial competitiveness needs to be boosted – starting with cleantech – in an international landscape characterised by more aggressive industrial policies. In tandem, Europe’s ‘open strategic autonomy’ must be safeguarded: dependencies on China, and possibly unreliable international partners in a wide range of strategic technologies and critical raw materials, have reached alarming levels.

A difficult dilemma for Europe lies at the core. How can we balance different political goals, such as climate neutrality by 2050 – as written into law by the European Climate Law – industrial competitiveness, social sustainability and fiscal discipline?

This briefing discusses various issues surrounding this dilemma and tries to propose a workable balancing act with which to move forward. To do so, it focuses on the investment needs for the green transition, emerging fiscal policy constraints, and the increasing importance of green industrial policies.

The EGD investment needs

The EGD strategic framework is rapidly evolving. While significant milestones were reached in 2022 and 2023, such as the adoption of extensive legislation that lays the groundwork for the climate and energy framework extending into 2030 and beyond, new policy and legislative initiatives are continuously launched by the European Commission (EC) to support the EGD under its different thematic pillars. The energy crisis and the current geopolitical circumstances – in particular, the need to end all dependence on Russian fossil fuels – have given a structural impetus to speed up the climate and clean energy transitions.

To meet the financial needs of the green transition, climate and the environment funding have been mainstreamed across EU programmes: 30% of the EU 2021-2027 budget and 37% of the EU recovery fund (Next Generation EU) have been devoted to climate action. This decision reflects the increasing recognition that green investments support economic growth and foster job creation. Substantial investments by both the public and private sectors need to be quickly scaled up in the EU within the next few years, especially in the buildings and transport sectors, if climate neutrality is to be achieved by 2050.

According to the EC’s estimates (EC, 2022a), to deliver on the EGD objectives, annual investments will need to increase by around EUR 520bn in the coming decade (2021-2030) (see Table 1). From those additional investments, EUR 390bn per year (corresponding to about 2.7% of EU-27 GDP in 2021), will go towards decarbonising the economy and, in particular, the energy sector, including energy-related investments in the buildings and transport sectors. This huge increase of more than 50%, compared to the historical energy investment trend, will also support EU efforts to ensure the security of energy supply as well as create jobs, lower energy bills of households and industry, and improve air quality and public health.

Table 1. Additional annual investment needs (2021-2030) for delivering on EGD environmental goals, compared to 2011-2020 (billion EUR)

Note: Numbers have been rounded up to whole figures.

Source: EC, 2022a.

Since 2019, the EC has prepared different estimates of the investment needs for achieving specific EGD environmental objectives or implementing selected EGD strategies (see Table 2). These overlap with the figures presented in Table 1. Table 2 includes the projection of the accumulated investment needs associated with boosting EU manufacturing capacity in some strategic net-zero technologies, i.e. solar, wind, batteries and storage, heat pumps and geothermal energy, electrolysers and fuel cells, biogas/biomethane, carbon capture and storage, and grid technologies, as part of the NZIA (EC, 2023a and 2023b), and ‘A Green Deal Industrial Plan’ for the Net-Zero Age (EC, 2023c). The estimated investment need is around EUR 92bn from 2023 until 2030, with a range between about EUR 52bn in the status quo scenario, to around EUR 119bn in the scenario with no dependence on imports[2].

Table 2. An overview of investment needs identified by EGD strategies/action plans

| EGD strategies and action plans (chronological order) and reference | Investment needs | Time period |

|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity Strategy, (EC, 2020a, COM(2020) 380 final) | EUR 20bn per year for spending on nature | 2020-2030 |

| Climate Target Plan, (EC, 2020b, COM(2020) 562 final) | EUR 350bn more per year for energy-related investments than invested in the 2011-2020 period[3] | 2021-2030 |

| Renovation Wave, (EC, 2020c, COM(2020) 662 final) | EUR 275bn per year for building renovation | 2020-2030 |

| Offshore Renewable Energy, (EC, 2020d, COM(2020) 741 final) | EUR 800bn for the large-scale deployment of offshore renewable energy technologies | 2020-2050 |

| Sustainable Mobility, (EC, 2020e, COM(2020) 789 final) | Additional investments (compared to the previous decade) of EUR 130bn per year for renewable and low carbon fuels infrastructure deployment + EUR 100bn per year to address the ‘green and digital transformation investment gap’ for infrastructure | 2021-2030 |

| Zero Pollution Action Plan, (EC, 2021a, COM(2021) 400 final) | Additional EUR 100-150bn every year to achieve environmental objectives beyond climate-related measures, a significant share of which is for pollution prevention and control investments | 2021-2030 |

| Solar Strategy, (EC, 2022b, COM(2022) 221 final) | Additional investments of EUR 26bn in solar PVs (on top of the investments needed to achieve the objectives of the Fit for 55 proposals) | 2022-2027 |

| RepowerEU, (EC, 2022c and d, COM(2022) 230 final and SWD(2022) 230 final) | Additional investments of EUR 210bn from now until 2027 and EUR 300bn until 2030 to deliver RepowerEU objectives (on top of the investments needed to realise the objectives of the Fit for 55 proposals)

– EUR 29bn in power grid investments by 2030 to enable greater electricity use – EUR 37bn to increase biomethane production by 2030 – EUR 41bn for adapting industry to use fewer fossil fuels by 2030 – EUR 56bn for energy efficiency and heat pumps by 2030 – EUR 113bn for renewables (EUR 86bn) and key hydrogen infrastructure (EUR 27bn) by 2030 – EUR 1.5-2bn for security of oil supply |

2021-2027/2030 |

| Climate adaptation – discussed in the Environmental Implementation Review 2022, (EC, 2022e, COM(2022) 438 final) | Based on investment needs reflecting the implementation objectives to 2020 and to 2030, climate adaptation costs can range from EUR 35-62bn (narrower scope) to EUR 158-518bn (wider scope) per year | 2021-2030 |

| Proposal of the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), (EC, 2023a and b, COM(2023) 161 final and SWD(2023) 68 final) | In the NZIA policy scenario[4] , the accumulated investment needs amount to around EUR 92bn over the period 2023-2030, with a range between about EUR 52bn in the status quo scenario, to around EUR119bn in the scenario with no dependence on imports. | 2023-2030 |

| EU Hydrogen Bank, (EC, 2023d, COM(2023) 156 final) | Total investment needs to produce, transport and consume 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen are expected to be in the range of EUR 335-471bn, with EUR 200-300bn needed for additional renewable electricity production.

The investments for key hydrogen infrastructure by 2030 are estimated at EUR 50-75bn for electrolysers, EUR 28-38bn for EU internal pipelines and EUR 6-11bn for storage. |

By 2030 |

Source: Own elaboration.

The additional investment needs cannot be raised by the public alone: the private sector must cover a substantial share. This is the concept behind sustainable finance where private funds complementing public money are crucial for the transition process, especially by funding long-term investments in sustainable economic activities and projects[5]. The split between the public and private role in financing additional investment needs is projected to range from a ratio of 1:5 (Darvas and Wolf, 2021), up to 1:2 (Baccianti, 2022), but will vary significantly between EU Member States. For example, the European Investment Bank (EIB) projected that about 60% of additional investments will be funded from public sources in Central and Eastern Europe and the share will only be 37% in western and northern Europe (EIB, 2021).

A shrinking macroeconomic space for green investments?

Fiscal sustainability may emerge as a long-term limitation for all public policies. The European macroeconomic policy environment is once again pervaded by fiscal discipline and the public budget criteria associated with the ongoing reform of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). Recently, public budgets have been heavily impacted by the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the energy crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result, the SGP was suspended for 2020-2023 and the EC presented a proposal to reform the EU fiscal rules in April 2023 (EC, 2023f)[6] . This proposal builds on the Maastricht Treaty reference values of a government budget deficit of 3% of GDP and a 60% debt-to-GDP ratio. The key reform proposal is the introduction of country-specific, medium-term fiscal-structural plans, which would be bilaterally negotiated between the respective Member States and the European Commission. The single operational indicator – net primary expenditure – displays whether or not the country-specific, credible, debt-reduction path is moving towards achieving the debt-to-GDP ratio of 60%. The risk from this revision process is that political will to increase public investment on transitions may fall short. This concern comes from past experiences, from policies implemented in the aftermath of the 2008/2009 global financial crisis (GFC) when public investment fell to almost zero in some EU Member States. Likewise, the COVID-19 pandemic boosted the debt-to-GDP level to rates higher than the ones Member States were confronted with at that time of the pandemic.

The new fiscal reality must also incorporate the projections that Europe will face less economic growth entailing weaker government revenues and thus, decreasing the financial scope of governments. In tandem, European governments are facing competition in allocating scarce public budgets. Solely focusing on higher public investment for the environment-energy-climate transition will miss the overall challenge of a sustainability transition in the evolving global macroeconomic and geopolitical framework. Policymakers are confronted with the dilemma of allocating public funds between spending priorities, which are either: mandatory as stipulated by law, e.g. social and health expenditures, or addressing other policy objectives such as financing the transition.

These fiscal and financial challenges include: digital transition; increases in military expenditure; investments in social infrastructure (as laid out in EC, 2018) and the public capital stock; high inflation followed by increases in the key interest rates by the European Central Bank leading to higher costs in public debt management (OECD, 2023 and Claeys et al., 2023); projected steady increases in the costs of an ageing population (EC, 2021d); keeping the competitiveness of the European economies intact (EC, 2023g and 2023h).

By way of example, the EC estimates that additional annual investment for digitalisation is projected to be in the range of EUR 125bn per year (EC, 2022a). Additional annual investment in social infrastructure, such as affordable housing, health and long-term care, education and life-long training, was estimated to be EUR 192bn (EC, 2021e) – deemed necessary in the context of social sustainability. Originally, it was estimated in the report of the High-level Task Force on Investing in Social Infrastructure in Europe that ‘The minimum infrastructure gap in social infrastructure investment is estimated at EUR 100-150bn per year and represents a total gap of over EUR 1.5tn (trillion) in 2018-2030 (EC, 2018)’. However, the gap increased because of the current crises.

EU Member States had noticeably decreased their net public investment, as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), after the global financial crisis (GFC 2007-2008), in comparison to previous decades. However, since around 2015, the share of public investment in GDP has again increased in most of the EU Member States. Net public investment is the decisive pillar for augmenting the capital stock in relation to output and should, therefore, be of critical interest in current times since a declining capital stock can erode the EU economy’s capacity to support future growth and prosperity. The EC estimated that ‘stabilising the capital stock … would require an increase in public investment (compared to spring 2020 forecast plans) of about EUR 100bn per year. Public investment tends to be lowest in Member States with high debt (EC, 2020f)’. It is worthwhile to highlight, when discussing investment and fiscal space, that in high debt-level EU Member States (with public debts over 90% of GDP), ‘net investments decreased to a GDP close to or even below zero’ (Blesse et al., 2023).

An increase in defence spending, as a response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, will also put fiscal pressure on the public budget of EU Member States, which are also NATO members, and are currently below the political commitment of spending 2% of the GDP on defence (Zettelmeyer et al., 2023 and NATO, 2022)[7].

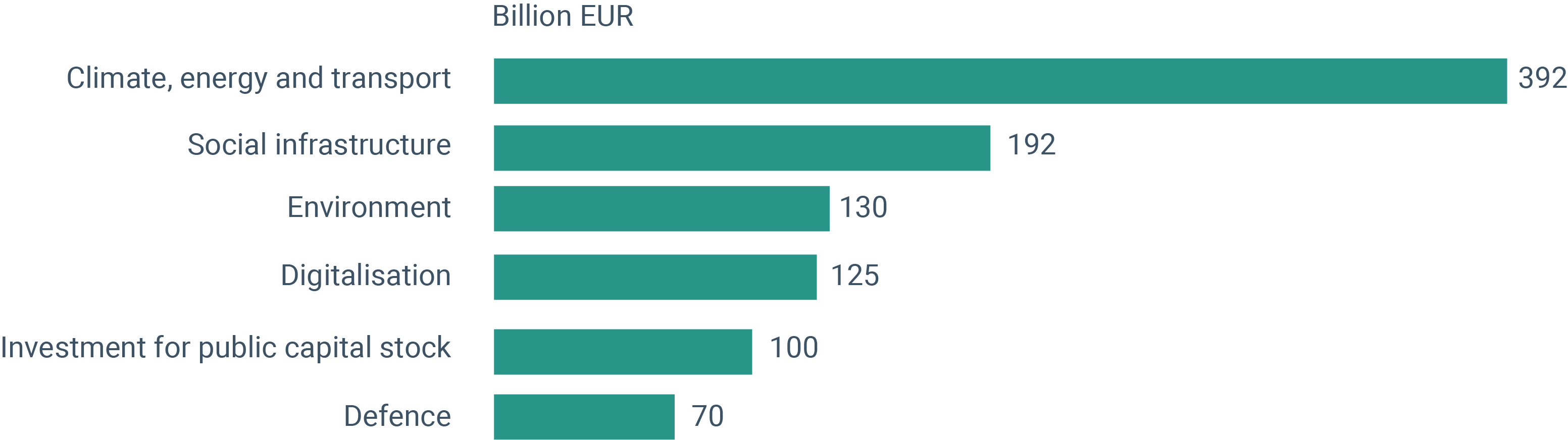

Presenting a systematic overview, in terms of additional investment needs of these fiscal challenges is complex. The underlying projections have different base years, and investments in the different policy areas may affect each other (Figure 1). However, it clearly reveals the enormous amount needed to cover the investment gaps as the gross fixed capital formation (investment) amounts to EUR 3.2tn in the EU-27 in 2021.

Figure 1. Annual investment needs in selected policy areas

Source: Investment needs to avoid a decline in the public capital stock: (EC, 2020f); social infrastructure (EC, 2021e); climate, energy, and transport; environment and digitalisation (EC, 2022a).

Another pressing challenge Europe is facing is the demographic transition: Ageing societies and demographic change, in terms of a shrinking population, are expected to lead to an increased demand for public expenditure, such as pensions, health and assistance, although EU Member States are affected differently (EEA, 2020). The latest projections published by the EC estimate that the total costs of ageing in the EU will increase by 1.4 percentage points (pps) of GDP between 2019 and 2030 and 2.5pps by 2050 compared to 2019, or more understandably, increase costs by 24-25.4% of GDP and 26.5% in 2050 respectively (EC, 2021d). This development is expected to strain productivity and economic growth in the EU (Blesse et al., 2023) and is a critical factor when assessing the fiscal sustainability of EU Member States[8].

What is even more important for policymakers is ‘to avoid a systematic trade-off between delivering on European investment priorities and the maintenance of healthy fiscal balances’ (Blesse et al., 2023), in particular, in the context of the legislative proposal to reform the EU fiscal rules. Furthermore, it is critical to highlight that the financing of investments in EU Member States via the Recovery and Resilience Fund, as the centrepiece of NextGenerationEU, will cease at the end of 2026. Member States must allocate at least 37% of the funds, identified in the country-specific Resource and Resilience Plans, to green transition measures amounting to EUR 216bn at EU-27 level[9]. Discontinuing these additional funds may lead to reduced efforts in financing public green infrastructure measures as otherwise national funds would have to be increased to offset the shortfall in EU funds set aside for green investments.

The challenge, therefore, is to achieve the balance between maintaining healthy fiscal systems and funding large and strategic investments towards a digital and green, climate-friendly society and economy[10]. Keeping the fiscal space sustainable could be achieved by cutting expenditures or improving the revenue side of the budget by increasing taxes. Another measure fostering green transition is the phasing out of environmentally harmful subsidies (EHS) as they are often economically inefficient and can distort trade. Such phasing out increases total tax-take public revenues and thereby provides further incentives for behavioural change and for investments in environmentally friendly technologies. However, the phasing out of EHS must consider the effects on low-income households as they may be disproportionately affected by this reform process. Additionally, decarbonising the energy sector will reduce Europe’s dependence on fossil fuel imports and the bill for energy imports.

New industry policy and ‘open strategic autonomy’: a lever to overcome constraints on public green investments[11]?

The industrial sector is crucial for the transition towards a competitive, digital and climate-friendly Europe. The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) (The White House, 2023) has sparked profound industrial competitiveness concerns across Europe and pushed the need for a new industrial policy. At a time in which the European industry is already under severe pressure due to high energy prices, the fear is that the IRA could push European cleantech manufacturers to move to the US in search of an attractive mix of IRA subsidies and low energy prices.

Such concerns are not new to Europe, e.g. the race for semiconductors with Japan in the 1980-1990s and the competition with China in several sectors including solar panels in the early 2000s. This time around though, things look even more complicated – the US enticingly puts forward a green industrial policy package that is both sizeable, simple and effective, i.e. USD 369bn in subsidies and tax credits for up to 10 years[12]. This mix makes the package particularly attractive for companies, putting the US on course to leapfrog Europe in the clean technology space.

This is particularly problematic since Europe is lagging behind Asia and the US in the global race for digital technologies. This increases pressure on Europe to be a leading force in the clean technology space – otherwise it will fail to reap the industrial benefits of the ongoing digital and green revolutions. The European economic fabric is highly reliant on energy-intensive industries, such as basic chemicals, iron and steel industries, which will be completely reshaped in the coming years. Turning jobs in these industries ‘green’ represents a key necessity for Europe to maintain and strengthen its socio-economic model in the future. Thus, the EU adopted the European Green Deal as its growth strategy and the Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age for tackling these problems.

In March 2023, the EC published the legislative proposal for an EU response to the IRA – the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) (EC, 2023a). The proposal pushes forward an industrial policy by promoting cleantech manufacturing organised in four steps:

- it specifies net-zero technologies that are considered to be strategic;

- the proposal plans to set an overall benchmark target for EU domestic manufacturing in these technologies to meet at least 40% of the EU’s annual deployment needs by 2030, as well as setting a target for an annual injection capacity in CO2 storage, promoting carbon capture and storage (CCS);

- a governance system is to be established for the identification of Net-Zero Strategic Projects (NZSPs) by Member States, with a minimal check by the European Commission. NZSPs should also involve technologies close to commercialisation and all projects must contribute to CO2 reductions, competitiveness and security of supply. This approach represents a reversal of current practice – where support was directed on earlier stages of technology development, including research, early-stage development and prototyping;

- a set of policy instruments is sketched out, mostly to be implemented at national level, to support the selected NZIA projects. The EC estimates that realising the 40%target of EU domestic manufacturing by 2030 will require EUR 92bn in investment, mainly to be funded by the private sector. In addition, the proposal includes the set up of a Net-Zero Europe Platform with different goals, such as promoting investment through the identification of specific projects to be supported by limited public subsidies, mainly at national level. The NZIA proposal does not allocate new EU level funding[13].

The NZIA might represent a useful first step in the process of creating a truly European green industrial policy and mobilising private investments for the transition. To do so, a broader agenda that can leverage the single market in a credible manner and build a solid new governance framework, as well as a new EU level funding approach, will be needed in the upcoming EU institutional cycle and is required for Europe to become a globally competitive, resilient, cleantech continent. The EU should strengthen its single market for goods, services, components, energy, capital, people and ideas.

Towards an EU green industrial policy agenda

Creating a comprehensive green industrial policy should be based on Europe’s greatest asset – the single market, since only a well-functioning, globally-linked EU market will have a similar scale to the domestic markets of the US and China. ‘Horizontal policies’ of the single market are crucial because the targeted ‘vertical policies’ established under the NZIA, such as permitting, public procurement and skills, will not be sufficient to deliver results at the required scale.

A successful transition process requires a new impetus to reform the single market, the banking union and capital markets union. The latter is crucial as the cost of accessing finance is imperative to the decision of companies to invest in clean technology. The EU financial system is still highly dominated by banks and fragmented along national lines. This may be a stumbling block since the financial system may not provide sufficient private capital to cover the enormous investment needed for the green transition. Since the creation of the banking union and the capital markets union with the objective of creating a truly single market for capital across the EU almost a decade ago, major policy initiatives have been initiated but have been blocked in recent years. A new push is required to stimulate these policy initiatives again as they are important components of a comprehensive EU response to the IRA.

An open and competitive single market can be seen as a precondition and lever for private cleantech investment. EU trade policy should not reverse and become protectionist because the EU will need to import intermediate goods and natural resources from non-EU countries– as these products cannot be competitively produced within EU borders – and to export products. These horizontal framework conditions will continue to be essential to EU competitiveness – as they have been in the past.

A key component in promoting a comprehensive green industrial policy is to have a proper functioning governance structure in place (Criscuolo et al., 2023). A proposal could be the creation of a competent and empowered institution that should be sufficiently politically independent or at least detached from any political pressures, assuring that the coordination and political steering of the process will be done at top-level. The achievements of the institution should be evaluated against clearly defined and realistic milestones and targets. It may be useful to study the US approach. President Biden appointed John Podesta as Senior Advisor to the President for Clean Energy Innovation and Implementation, and Chair of the President’s National Climate Task Force, after the Inflation Reduction Act was approved. The governance process is not only important in the context of green industrial policy but also in the broader, longer-term socio-economic and political sustainability of the European Green Deal and its underlying objective of being Europe’s new growth strategy. A further political benefit in appointing an EU counterpart to Podesta is that it might pave the way to improve EU-US coordination of green industrial policy. A year ago, the US launched the IRA and Europe feared a trade war – because of the subsidies and the potential diversion of clean technology investments away from Europe.

Achieving these goals will be a challenge, but the EU may consider following the steps of the US in setting up its own version of the US Advanced Research Projects Agency, with the emphasis on Energy and Climate, and aimed at fostering high-risk, early-stage development projects for new cleantech manufacturing technologies[14]. Such an institution may also play a pivotal role in developing complementary funding schemes, both at national and EU level, and connect to existing funding organisations like the European Research Council (ERC) and the European Innovation Council (EIC). Work should not be duplicated. This ensures that the ERC and EIC maintain their focus on supporting bottom-up ideas and balancing top-down cleantech NZIA programmes – alongside the European Investment Bank (EIB) as the biggest multilateral financial institution and a key player in financing climate action and environmental sustainability. Furthermore, it may be prudent to develop and employ a new EU level funding strategy in a green industrial policy setting, aiming to tackle the risks of single-market fragmentation and the political tensions between EU Member States, as well as further promoting the establishment of an integrated capital market in the EU. Otherwise, the threat is that richer EU countries may support private investment in cleantech by providing public incentives from national state aid and thereby impairing fair competition within the EU[15].

Reflections

The implementation of the EGD demands a huge amount of investments – around EUR 520bn per year in the present decade (2021-2030), of which EUR 390bn per year goes towards energy transition and the decarbonisation of the economy. This figure is 50% higher than the historical energy investment trends. Additional investment needed to boost EU manufacturing capacity, in some strategic net-zero technologies addressed by NZIA, is around EUR 92bn over the period 2023-2030.

The question of how this huge amount of public financial resources can be fully mobilised is now made even more urgent and challenging by the new macroeconomic, fiscal and political landscape for Europe. Fiscal sustainability is emerging as a forefront limitation on all public policies, the return to fiscal discipline, and the public budget criteria associated with the ongoing reform of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). European governments are facing competition in allocating scarce public budgets, such as digital transition, increase in military expenditure, investment in social infrastructure, the increase in the costs of an ageing population, high inflation followed by increases in the key interest rates and higher costs in public debt management. The risk from this process is that the political will to increase green transition investment will fall short.

The design and implementation of a new green industrial policy, within the high-level policy of ‘open strategic autonomy’, can be one of the levers to avoid possible standstills in green public investments and to pave the way to a deeper commitment of the private sector in the sustainability transition.

In 2023, the NZIA proposed to prioritise the development of strategic cleantech manufacturing that can be a first step in the pathway. Furthermore, creating a comprehensive green industrial policy should be based on Europe’s greatest asset – the single market. To achieve a globally competitive, cleantech powerhouse, Europe cannot rely on fragmented national measures because they will not steer private investments in clean technology at the scale and speed that is needed. ‘Horizontal policies’ of the single market are crucial since the targeted ‘vertical policies’ established under the NZIA, such as permitting, public procurement and skills, will not be sufficient to deliver results at the required scale.

Acknowledgments

Authors:

Speck, Stefan (EEA); Paleari, Susanna (ETC/CE – Research Institute on Sustainable Economic Growth of the National Research Council of Italy (IRCrES); Tagliapietra, Simone and Zoboli, Roberto (ETC/CE – Sustainability, Environmental Economic and Dynamics Studies (SEEDS), Catholic University Milan, Italy)

Notes

[1] For example, see President Macron’s call for pause of environmental regulation: (https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2023/05/12/macron-calls-for-pause-of-european-environmental-regulation-confusion-ensues_6026448_5.html), as well as the comments made by the German Minister of Finance (https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-finance-minister-christian-lindner-eu-dangerous-green-plans-clean-energy/) and Dennison and Engström (2023)

[2] Other EC estimates from the 2023 strategic foresight report (EC, 2023e) indicate that ‘additional investments of over EUR 620bn annually will be needed to meet the objectives of the Green Deal and RepowerEU’.

[3] The investment needs were revised upwards to about EUR 390bn (see Table 1), and in more detail see: COM(2021) 557 final and SWD(2021) 621final.

[4] NZIA policy scenario: The EU manufacturing market shares of the strategic net-zero technologies (focusing on wind, solar PV, heat pumps, batteries and electrolysers) are boosted to reach the indicative technology-specific objectives outlined in the recitals to the Net-Zero Industry Act Proposal.

[5] For more information on the EC’s work on sustainable finance: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance_en

[6] For more information and detailed discussion on the proposal: Kauder et al., (2023), the policy brief of the European Trade Union Institute (Theodoropoulou, 2023), the note published by Bruegel (Darvas, 2023) and Schmidt (2023).

[7] The European Defence Agency (EDA) specified that ‘spending is set to grow by up to EUR 70bn by 2025, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forces a paradigm shift in Europe’s foreign and defence policy’ (EDA, 2022).

[8] See, for example, the report of the Irish Department of Finance highlighting the fiscal risks and challenges evolving with an ageing society, when assessing how to make the Irish fiscal system future-proof at a time of multiple crises (Department of Finance, 2023).

[9] For information on the share of funds dedicated to the green transition in Member States’ resource and resilience plans: https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/european-union-countries-recovery-and-resilience-plans

[10] During the discussion of reforming the SGP, several proposals were made to introduce a golden rule of excluding green public investment from the calculation of the 3% budget deficit rule and thereby safeguarding the required investment expenditures for the green transition. For further discussion and literature: Bénassy-Quéré, 2023, and Blesse et al., 2023.

[11] The following parts are based on work published by Bruegel (www.bruegel.org), Tagliapietra et al., 2023a and 2023b, and Kleimann et al., 2023.

[12] Since the volume of tax credits is not capped, estimations project that the volume of the support programme may be twice (Credit Suisse, 2022), or three times (Bistline et al., 2023) the office estimate.

[13] In June 2023, the EC proposed the mid-term review of the EU budget – the ‘Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform’ (STEP), with the objective of supporting the industrial transformation by reshuffling money from existing programmes, such as the cohesion policy and recovery and resilience facility (RFF) funds, as part of the Green Deal Industrial Plan.

[14] For a more detailed discussion on this topic, see Aghion, 2023.

[15] See the article ‘Brussels showdown brews with Paris and Berlin over lavish energy subsidies’ https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-energy-subsidy-france-germany-commission-handouts/

References

Aghion, P., 2023, ‘An innovation-driven industrial policy for Europe’, in: Tagliapietra, S. and Veugelers, R. (eds), Sparking Europe’s New Industrial Revolution: A policy for net-zero, growth and resilience, Bruegel Blueprint Series 33, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/book/sparking-europes-new-industrial-revolution-policy-net-zero-growth-and-resilience).

Baccianti, C., 2022, ‘The Public Spending Needs of Reaching the EU’s Climate Targets’, in: Cerniglia, F. and Saraceno, F. (eds), Greening Europe — 2022 European Public Investment Outlook, (https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0328).

Bénassy-Quéré, A., 2023, ‘How to ensure that European fiscal rules meet investment’, VoxEU (https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/how-ensure-european-fiscal-rules-meet-investment).

Bistline, J., et al., 2023, Economic implications of the climate provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, Working Paper 31267, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA (https://www.nber.org/papers/w31267).

Blesse, S., et al., 2023, A Targeted Golden Rule for Public Investments?, EconPol Policy Report 42/2023, CESifo Research Network (https://www.econpol.eu/publications/policy_report_42)

Claeys, G., et al., 2023, The rising cost of European Union borrowing and what to do about it, Policy Brief 12/2023, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/PB%2012%202023.pdf).

Credit Suisse, 2022, Treeprint: US Inflation Reduction Act, Credit Suisse (https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us-news/en/articles/securities-research-reports/report-13-202205.html).

Criscuolo, C., et al., 2023, ‘Industrial strategies for the green transition’, in: Tagliapietra, S. and Veugelers, R. (eds), Sparking Europe’s New Industrial Revolution: A policy for net-zero, growth and resilience, Bruegel Blueprint Series 33, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/book/sparking-europes-new-industrial-revolution-policy-net-zero-growth-and-resilience).

Darvas, Z., 2023, Fiscal rule legislative proposal: what has changed, what has not, what is unclear?, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/fiscal-rule-legislative-proposal-what-has-changed-what-has-not-what-unclear).

Darvas Z. and Wolff, G., 2021, A green fiscal pact: climate investment in times of budget consolidation, Policy Contribution 18/2021, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp_attachments/PC-2021-18-0909.pdf).

Dennison, S. and Engström, M., 2023, Ends of the earth: how EU climate action can weather the coming election storm, European Council on Foreign Relations, Policy brief, September 2023, https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ends-of-the-earth-How-EU-climate-action-can-weather-the-coming-election-storm.pdf

Department of Finance (Ireland), 2023, ‘Future-proofing the Public Finances – the Next Steps’, (https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/8a0a8-future-proofing-the-public-finances-the-next-steps/).

EC, 2018, Boosting Investment in Social Infrastructure in Europe Report of the High-level Task Force on Investing in Social Infrastructure in Europe, Discussion Paper 074, European Commission (https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/boosting-investment-social-infrastructure-europe_en).

EC, 2020a, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 Bringing nature back into our lives’ (COM(2020) 380 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:a3c806a6-9ab3-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF).

EC, 2020b, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition Investing in a climate-neutral future for the benefit of our people’ (COM(2020) 562 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0562&rid=8).

EC, 2020c, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘A Renovation Wave for Europe – greening our buildings, creating jobs, improving lives’ (COM(2020) 662 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0662).

EC, 2020d, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘An EU Strategy to harness the potential of offshore renewable energy for a climate neutral future’ (COM(2020) 741 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2020%3A741%3AFIN).

EC, 2020e, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy – putting European transport on track for the future’ (COM(2020) 789 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0789).

EC, 2020f, Commission Staff Working Document ‘Identifying Europe’s recovery needs. Accompanying the document ‘Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation’ (SWD(2020) 98 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020SC0098&from=EN).

EC, 2021a, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Pathway to a Healthy Planet for All EU Action Plan: “Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil”’ (COM(2021) 400 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DA/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:400:FIN).

EC, 2021b, Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 98/70/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 (COM(2021) 557 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:dbb7eb9c-e575-11eb-a1a5-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF).

EC, 2021c, Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and the Council amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 98/70/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 (SWD(2021) 621 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:0f87c682-e576-11eb-a1a5-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF).

EC, 2021d, The 2021 Ageing Report Economic & Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019-2070), Institutional Paper 148, European Commission (https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/2021-ageing-report-economic-and-budgetary-projections-eu-member-states-2019-2070_en).

EC, 2021e, Commission Staff Working Document ‘Scenarios towards co-creation of a transition pathway for a more resilient, sustainable and digital Proximity and Social Economy industrial ecosystem’ (SWD(2021) 982final), European Commission (https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/consultations/scenarios-towards-co-creation-transition-pathway-resilient-innovative-sustainable-and-digital_en).

EC, 2022a, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Towards a green, digital and resilient economy: our European Growth Model’ (COM/2022/83/final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0083).

EC, 2022b, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘EU Solar Energy Strategy’ (COM(2022) 221 final), European Commission (https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-05/COM_2022_221_2_EN_ACT_part1_v7.pdf).

EC, 2022c, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘REPowerEU Plan’ (COM(2022) 230 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A230%3AFIN).

EC, 2022d, Commission Staff Working Document ‘Implementing The RePowerEU Action Plan: Investment Needs, Hydrogen Accelerator and Achieving the Bio-Methane Targets’ (SWD(2022) 230 final), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022SC0230&from=EN

EC, 2022e, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Environmental Implementation Review 2022 Turning the tide through environmental compliance’ (COM(2022) 438 final), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=comnat%3ACOM_2022_0438_FIN).

EC, 2023a, Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council ‘on establishing a framework of measures for strengthening Europe’s net-zero technology products manufacturing ecosystem (Net-Zero Industry Act)’ (COM(2023) 161), European Commission (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:6448c360-c4dd-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF).

EC, 2023b, Commission Staff Working Document ‘Investment needs assessment and funding availabilities to strengthen EU’s Net-Zero technology manufacturing capacity’ (SWD(2023) 68 final), European Commission (https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/SWD_2023_68_F1_STAFF_WORKING_PAPER_EN_V4_P1_2629849.PDF).

EC, 2023c, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age’ (COM(2023) 62 final), European Commission (https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-02/COM_2023_62_2_EN_ACT_A%20Green%20Deal%20Industrial%20Plan%20for%20the%20Net-Zero%20Age.pdf).

EC, 2023d, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘on the European Hydrogen Bank’ (COM(2023) 156 final), European Commission (https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/COM_2023_156_1_EN_ACT_part1_v6.pdf).

EC, 2023e, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council ‘2023 Strategic Foresight Report Sustainability and people’s wellbeing at the heart of Europe’s Open Strategic Autonomy’ (COM(2023) 376 final), European Commission (https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-07/SFR-23_en.pdf).

EC, 2023f, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council ‘on the effective coordination of economic policies and multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97’ (COM(2023) 240 final), European Commission (https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-04/COM_2023_240_1_EN.pdf).

EC, 2023g, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Long-term competitiveness of the EU: looking beyond 2030’ (COM(2023) 168 final), European Commission (https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/Communication_Long-term-competitiveness.pdf).

EC, 2023h, Employment and Social Developments in Europe Addressing labour shortage and skills gaps in the EU, European Commission (https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&furtherNews=yes&newsId=10619).

EDA, 2022, Investing in European defence — Today’s promises, tomorrow’s capabilities?, European Defence Agency (https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9acc6113-751d-11ed-9887-01aa75ed71a1/language-en).

EEA, 2020, The sustainability transition in Europe in an age of demographic and technological change: an exploration of implications for fiscal and financial strategies, EEA Report No 23/2019, European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/sustainability-transition-in-europe).

EIB, 2021, Investment Report 2020/2021 building a smart and green Europe in the COVID-19 era, European Investment Bank (https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/32177fdd-643f-11eb-aeb5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en).

Kauder, B., et al., 2023, Reforming Economic and Monetary Union. Balancing Spending and Public Debt Sustainability, Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies (https://www.martenscentre.eu/publication/reforming-economic-and-monetary-union-balancing-spending-and-public-debt-sustainability/).

Kleimann, D., et al., 2023, Green tech race? The Inflation Reduction Act and the Net-Zero Industry Act, The World Economy (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/twec.13469). NATO, 2022, Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), North Atlantic Treaty Organization (https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_197050.htm).

OECD, 2023, OECD Sovereign Borrowing Outlook 2023, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (https://www.oecd.org/publications/oecd-sovereign-borrowing-outlook-23060476.htm).

Schmidt, V., 2023, Making EU Economic Governance Fit for Purpose: Investing in the Future and Reforming the Fiscal Rules While Decentralizing and Democratizing, 4/2023 Volume 24, EconPol Forum (https://www.cesifo.org/DocDL/econpol-forum-2023-4-schmidt-eu-governance-purpose-future.pdf).

Tagliapietra, S., et al., 2023a, ‘Europe’s green industrial policy’, in: Tagliapietra, S. and Veugelers, R. (eds), Sparking Europe’s New Industrial Revolution A policy for net-zero, growth and resilience, Bruegel Blueprint Series 33, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/book/sparking-europes-new-industrial-revolution-policy-net-zero-growth-and-resilience).

Tagliapietra, S., et al., 2023b, Rebooting the European Union’s Net-Zero Industry Act, Bruegel Policy Brief 14, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/rebooting-european-unions-net-zero-industry-act).

The White House, 2023, Inflation Reduction Act Guidebook: Building a clean energy economy, Version 2, The White House, Washington, DC (https://www.whitehouse.gov/cleanenergy/inflation-reduction-act-guidebook/).

Theodoropoulou, S., 2023, The European Commission’s legislative proposals on reforming the EU economic governance framework: a first assessment, ETUI Policy Brief 2023.04, European Trade Union Institute (https://www.etui.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/04.2023.PolicyBrief-V01.pdf).

Zettelmeyer, J., et al., 2023, The longer-term fiscal challenges facing the European Union, Policy Brief 10/2023, Bruegel (https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/longer-term-fiscal-challenges-facing-european-union).

Identifiers

Briefing no. 20/2023

Title: Investments in the sustainability transition: leveraging green industrial policy against emerging constraints

EN HTML: TH-AM-23-024-EN-Q – ISBN: 978-92-9480-600-0 – ISSN: 2467-3196 – doi: 10.2800/05294

EN PDF: TH-AM-23-024-EN-N – ISBN: 978-92-9480-599-7 – ISSN: 2467-3196 – doi: 10.2800/451268