In the first two trading periods of the EU ETS (2005-2007 and 2008-2012), most allowances were given out in large amounts for free, pushing the price for first-period allowances to zero in 2007.

In its third phase (2013-2020), 40 percent of allowances were auctioned, pushing electricity producers to buy all their allowances (with exceptions in some member states like Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, etc). From 2021, around 57 percent of the union-wide cap is auctioned, and only Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania decided to continue allocating free allowances to the energy sector.

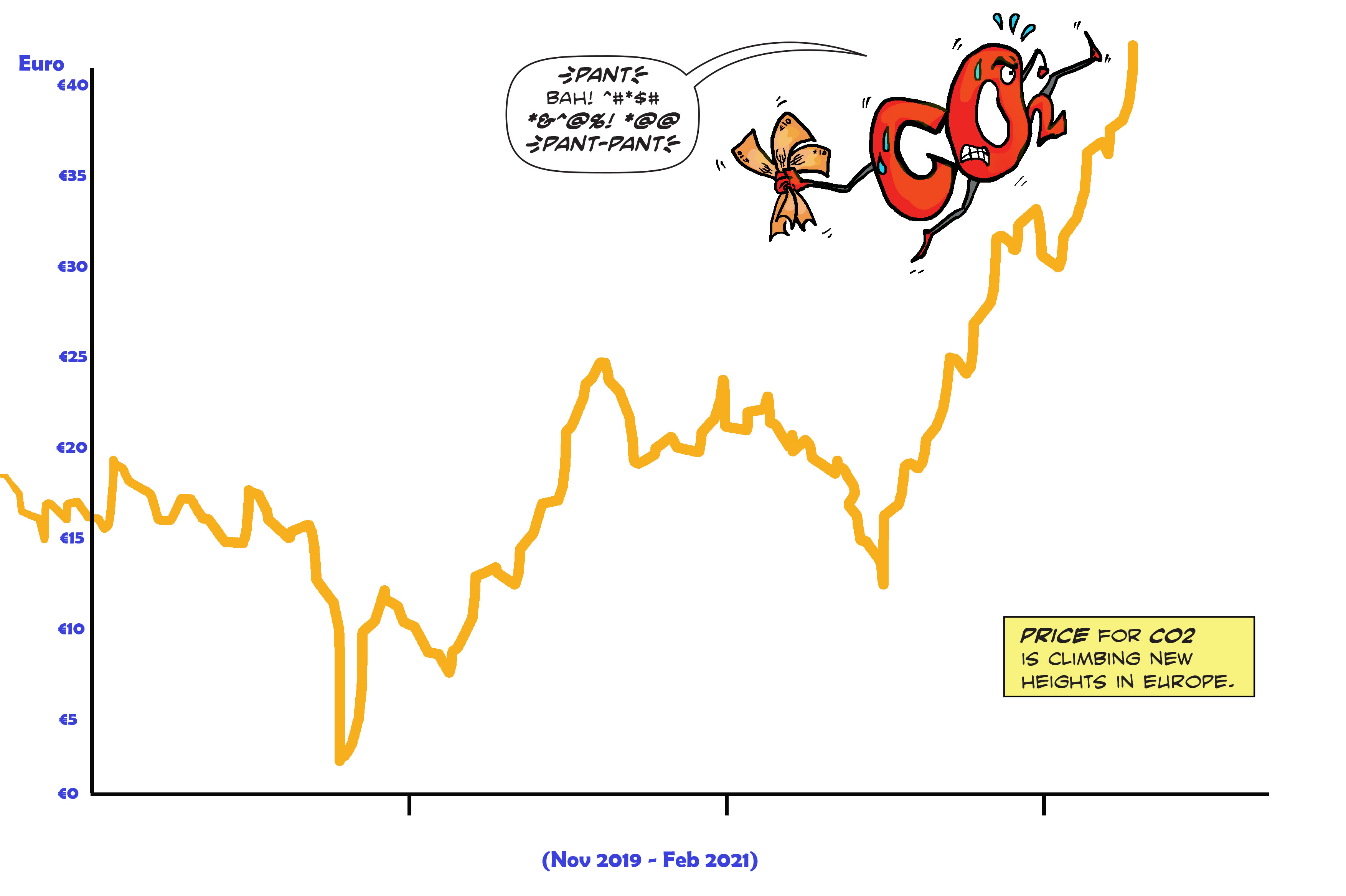

Still, free allocation prevailed in manufacturing and aviation, and sectors deemed to be at risk of ‘carbon leakage’ also received an extra amount of free allowances. As a consequence of the generous distribution of free emissions allowances, prices for permits were never as high as envisaged. The surplus of permits grew even greater after the 2008 economic crisis caused emissions to fall faster than anticipated (production in the steel industry alone declined by 28 percent between 2008 and 2009). The price fell from 30 euros per allowance in 2008 to 2.75 euros in 2013.

During the system’s 2018 reform, a reduction in the number of permits distributed for free was agreed upon. As part of this reform, in the programme’s fourth phase (2021-2030), the number of economic sectors deemed to be at risk of carbon leakage, and thus entitled to free emissions allowances, were cut. With the agreements on reforms of the system, permit prices rose considerably, from 9.68 euros in 2018 to a record of 100 euros in early 2023.

However, the price fell again to about 60 euros by early 2024 due to several reasons. Reduced gas prices mean that electricity is produced with lower emissions, and shrinking energy demand from industry pushes down the need for allowances in the sector, said Hæge Fjellheim, of carbon market intelligence company Veyt. In addition, the EU accelerated the energy transition and reduced dependence on Russian fossil fuels through its REPowerEU plan. One element of this plan is to finance measures by selling ETS allowances earlier than planned (“frontloading”), which results in more allowance supply in the years 2023-2026. This also has a price-dampening effect in those years. Eventually, prices will rise again, wrote Veyt, forecasting 130 euros per allowance in 2030. Other analysts also see prices rise in the coming years, albeit slower than initially forecast.